Sydney Road Poems by Carmine Frascarelli

Rabbit Poets Series, 2016

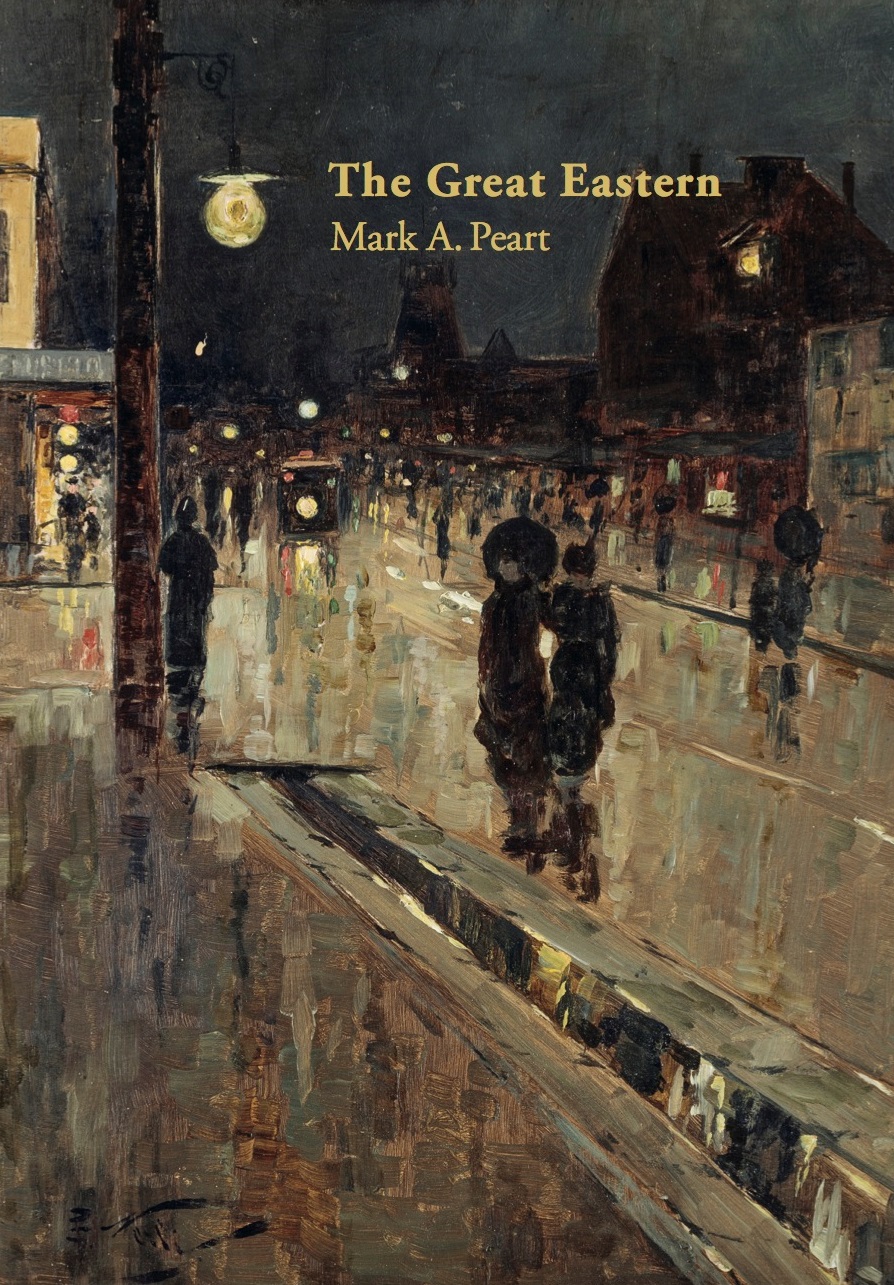

The Great Eastern by Mark A Peart

Rabbit Poets Series, 2016

In the nonfiction poetry issue of Axon that she co-edited with Ali Alizadeh, Jessica L Wilkinson highlights the impact that Jordie Albiston’s The Hanging of Jean Lee had on her as an undergraduate in 2001. Albiston’s collection is a poetic biography of Lee, the last woman to be executed in Australia. Wilkinson would later be influenced by Susan Howe – whose practice both informed and was a focus of Wilkinson’s doctoral study – to found Rabbit: a Journal of Non-fiction Poetry in 2011; however, a line can be traced from the early impact of Albiston’s book, to the journal, and on to the fledgling Rabbit Poets Series, which began with Albiston’s XIII Poems in 2013.

In January I found The Hanging of Jean Lee in a secondhand bookstore in Hornsby, and find my thoughts returning to it again and again whilst reading Mark A Peart’s The Great Eastern (#5 in the Rabbit Poets Series): a long poem drawing on witness deposition and proposing a poetic defense for a man known by the titular name, ‘who perambulated the streets of Collingwood and Fitzroy in women’s dress during the early 1860s soliciting men for sex.’ In Peart’s introduction are assorted pronouns – ‘they’, ‘her’, ‘his’, ‘she’, ‘he’ – and, interestingly, this fluidity remains evident even in the condemnatory contributions from The Great Eastern’s lovers and patrons. James Morris reports: ‘if you observe that / woman walking / in Victoria Parade / remember it’s a man’. John James knows the prisoner ‘by the looks of him. / he was dressed as / a man or a woman.’ The striking out of words replicates those struck out in the record of the Victorian Supreme Court case of The Queen v. John Wilson (1863), used by Peart alongside court and newspaper archives, as the source material for the poem.

The above examples are indicative of the purgative poetics in the poem’s deposition sections. These appear throughout the collection in pairs, perhaps a presentation of the doubled existence of John Wilson / The Great Eastern. Those on the left are composed from the words of witnesses – Morris, James and other Johns (Jones, Morgan and McKeevor); Joseph Wheeler; Edward Turner; and Bartholomew O’Donnovan. Distanced by Peart’s voice from the questions that prompted them, their origins obscured from judge, jury and reader, the men’s answers gain some odd strength. In isolation they become more sinister, they become statements; no longer a response but an attack. They lead the charge. This affect reflects the poem’s beginning, where Morris offers yet more antonyms for our subject – Ellen Maguire, and, more distressingly, ‘the prisoner’. Each repetition of the latter in subsequent pages feeds our unease towards the fate of the Great Eastern, in spite of what is known to be an inevitability.

Pages on the right offer the voice of The Great Eastern, unbound by the constrictions of attribution and occupying multiple perspectives. Unsurprisingly, the voice here treads over gender innocuously. On the first such page we see ‘a woman walking / musth the parade’; musth, from the Urdu mast (‘intoxicated’), refers to the reproductive hormonal rush that turns elephant bulls bellicose. This is no hagiography: at least two punches are thrown (and three received), kneecaps are kicked, cunts are called just that, and there’s no effort made to conceal a taste for tipple. Despite this, it feels short on the biographical front. Where Albiston traced Lee’s life from childhood to chair, Peart’s timeframe is tighter, little more than two years, but offers glimpses of the self, shouted out.

The Great Eastern’s version of events accompanying deposition VI is particularly revealing about the collection as a whole. Turner, Morgan and James are in a house on Young Street, late December, 1863. As the two Johns wait downstairs Turner plays the role of one overhead:

turner’s fat little cock jams in. he moans like a lamb in distress his face a hawk convulsing between the two

With Turner taking the parts of lamb and hawk the ‘prisoner’ is neither perpetrator nor prey, but witness, an elephant in the room. By contrast, Carmine Frascarelli’s turn as witness feels less triumphant. Elsewhere in her Axon paper, Wilkinson contends that, ‘through poetry and experiment, narratives of the past might be enlivened to meet those characters and events in writing more uniquely and appropriately than may be encountered through more traditional historical modes.’ Despite the assortment of non-fictional bumf that informs and (re)enforces Frascarelli’s Sydney Road Poems (#7 in Rabbit Poets Series), it does not amount to that which we so often presume or expect from any non-fictional writing: the/an answer.

In the author’s statement appended to the collection we gain some insight into the questions that prompted this assorted response; a plurality of contesting truths. Looking at our precarious civility and the roots of violence running deep in our history, Frascarelli asks:

Will we learn without confronting it?

Can we learn by confronting it?

How do you outrun,

how do we beat history as we become it?

Earlier in his statement is an offhand remark about the physical fights – ‘we’d hit each other, smash things’ – between he and an ex-partner. This prompts another, difficult question: in asking how we beat history, is the desire to defeat it or to strike it? Sydney Road Poems depicts the ‘desperate chaotic design underlying most of what stretches out beneath us’, and doesn’t flinch at the seediness the poet rightly expected to unearth with research. As an investigation into the roots of violence in this country, however, it feels too distanced from the guilt expressed and acknowledged in the afterword.

Wilkinson (that is, Jessica) is not the only J Wilkinson to contribute in some part to Carmine Frascarelli’s Sydney Road Poems. The poem ‘#26’ stamps business names and proprietors thickly atop one another, and among the cacophony of ink can be spotted J Wilkinson, printer, 1885. There is yet another Wilkinson who has contributed in more oblique ways to the collection; Thomas Wilkinson owned and occupied the lone house from which the City of Brunswick was born. It is Brunswick for the most part in which Frascarelli, as flaneur, walks and writes. The trio of Wilkinsons could simply be coincidence, but it is these and similar seemingly unconnected contributions – to place, to poem – that aggregate and create something akin to Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, or Kenneth Goldsmith’s Capital (inspired by the former), in abridged form. To paraphrase Frascarelli in poem #36, we ‘get an idea of the particulars lost in the quantity / setting the bulk.’ Where Peart shows how someone may occupy and operate within a space, Frascarelli presents the two entities – person and place – as inseparable, and this ecological framing seems to attempt an immunity for the acts of the individual.