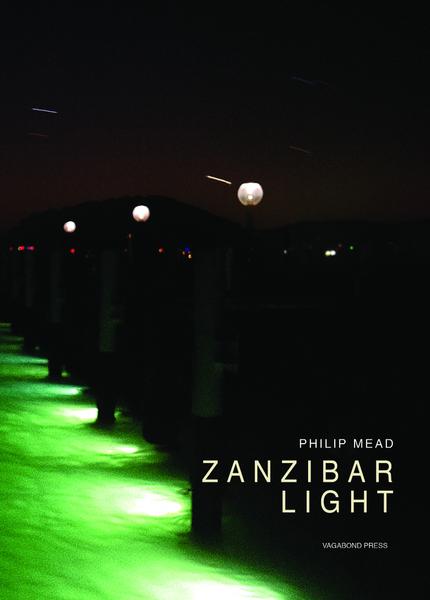

Zanzibar Light by Philip Mead

Vagabond Press, 2018

‘Words have a universe of qualities other than those of descriptive relation: Hardness, Density, Sound-Shape, Vector-Force, & Degrees of Transparency/Opacity.’ – Clark Coolidge1

For experimental poet and jazz drummer Clark Coolidge, words are never impressions. They are sonic inscriptions, vectors, movable actualities. They alter by degrees in the company of others and in time. I started with Coolidge for many reasons; first among them, his stellar understanding of improvisation.

Philip Mead’s new book Zanzibar Light is at home with the idea that words themselves are a kind of improvised approximation. They are musically dense, historically freighted, intense in their vocalised intimacy, and humming with Coolidge’s ‘universe of qualities’ – to which I would add light and lightness. The poems in this collection fizz with erudition that is worn lightly: ‘sections of the national lake appear / in your arrangements, but there’s no myth anywhere I can see, / only material.’

By opening his book with the short lyric ‘Cumquat may’, Mead riffs on the importance of punning as a key and serious improvisational vehicle carrying these poems. I think the pun almost works as a leitmotif for Zanzibar Light. Puns embody a splendid insistence on every word being unoriginal – but since there is ‘no such thing as repetition’2 in a post-Steinian poetic, every pun ghosts a kind of ur-originality. Light is, of course, another of the book’s signatures – punning on itself, a leitmotif bundled into a knowing title, a leading statement. The book’s many extemporisations on light are open-ended, numerous in effect and resonance as much as presence. They are, after Coolidge, ‘other than descriptive’, and never about a dogged conversation between words and things. ‘Sideways platinum cornettes of light’, ‘whirring light’, ‘tiny lights / from the other side’, ‘Lightly institutionalised behaviours’ – Mead improvises upon light at the level of grammar, sound, perceptual field and emotional texture. Or as he writes in a poem beginning ‘happy days, bold geraniums’:

Nothing we want any more is credited, what with the damp, zinc-matte, blue-white of dawn, the words going back and then forth boundlessly, it’s like a thick network of reference, or washed away

Zanzibar Light is the composition of a dedicated and careful listener. Good listeners make the best improvisers. Mead hears the ideational history behind many of his lines, washing about ‘like a thick network of reference’. Punning on his own distinguished contributions to contemporary innovative poetics in Australia, he ventriloquises a library or two – ‘the words going back and / then forth boundlessly’ – aware he’s coming to readers from the other side of ‘time and language’, making it new, repetition and difference, and the status of concepts as objects. ‘Any idea how many layers you might be dealing with?’, quips a poem beginning with the nifty axiom ‘cones and bollards have been the ruin of our youth’.

These are not inventions that lionise the poetic image, or the transcendent experiential moment, or the artifice of narrative completion. Nor do they reify language as it constitutes and transforms reality. At all points, however, they pun upon these critical histories and their non-stop repurposing as commodities in a system of literary and cultural capital, even while keeping their work alive – un-relegated and human – in a babble of voices moving through. ‘A chorus / of manouevres charges past at a furious pace, you’d hope everything / stays open for another hour at least, before being relegated / to sayings?’. Ideas are cared for by the people who make and use them, ‘lovely and runaway’ like a garden.

This book is full of people: children, partners, friends, characters, authors, internet memes. It’s wildly social, operatically un-isolated. A poem might deliberate for an instant upon an ecology or habitat – a ‘rocky inter-tidal zone’ or ‘a paddock with thin mist and occasional crows’ – but these are populated spaces, thresholds to communities. Mead’s reflections on place are always mediated by a political awareness of human territorialising, and the labours of language in surveilling or indexing ‘landscapes’ and their aesthetic functions. In the poem ‘Greetings from the heart of the country’, Mead enters the technologies that settle, generate and police something he calls ‘our vantage point’ – a collective imaginary, perhaps, or ‘a record of our national selves’, in which “weather” is partially a synecdoche for country and nation:

Now a computer-generated coastline swims into view, nautilus-wise from our vantage point among the weather satellites that’s real world data, including the little spikes of order scrolling across the screen; our pilot has frank, grey eyes.

Such poems gently perform a reckoning of decades in which Australian culture has been repositioned, slowly at times, within a globally interlinked economy. Zanzibar Light swings across half a century and acknowledges local, communal and cultural gains and damages along the way, including the social and post-colonial fallout of severely stratified wealth: ‘way below the slipstream of contemporary social life those subsist / who can’t accept any of the messages, who can only shake’. The book never loses sight of what Mead calls ‘Things / in their everyday zones’, including hubs of power that shape real lives. ‘No doubt the open country of daily life has a lot to offer’ he observes, ‘but it’s hard to cross, troublematic.’ Satire is applied with a light brush: ‘The world is a weird village / of established goals’.

I briefly want to note three more formal improvisations. I love the contents listing of this book and it deserves a slow read. Comprising mostly first lines, it prefigures their later appearance in poems, stitching them into a kind of self-sampling prologue and echoing the book’s indexical logic. This creates a happy polyphony, a foundational chaos of part and whole. Secondly, it would be remiss not to mention sonnets. Mead finds more to do with sonnets than we might imagine possible, moving deftly from unbroken 14-line lozenges to sonnets in stanzas and couplets, or 28-line poems that double a sonnet’s stakes and turns (lines ‘return’ and ‘overturn’ in ‘Roadside Grass’). The book flicks from one sonnet to another, sometimes punctuating first and last lines so they feel like syntactical run-ons from previous poems or conceptual bridges to the next, and elsewhere keeping poems discrete. There is nothing formulaic about the ways Mead’s sonnets interact. Sections one and two read like radical estrangements of the fifteenth century ‘sonnet corona’, further ad-libbing on light and its ‘circles of story’.

Thirdly, the opening and closing poems condense the sonnet’s lyrical impulses into paired 10-line blazons – in the fashion that John Tranter understands John Ashbery’s use of the term: an ‘emblem / of the work itself, a tiny mirror for the plot’.3 Vital tropes enter and depart like theme tunes in both lyrics, one addressed to Mead’s partner and one to a fellow poet, Gig Ryan. Together, the most private and public of relationships hold up this suspended net of poems, through which light and water pass easily as a lifetime of conversations.

Philip Mead makes a brilliant return to poetry publishing with Zanzibar Light. I recommend the book as the feat of a principled innovator who has spent years listening closely to ‘the source code whose portability is illumined’ in the act of writing with, and for, others.

Source poems

p.43, ‘sundown’: ‘sections of the national lake appear […]’

p.17, ‘Sideways’: ‘Sideways platinum cornettes of light’

p.66, ‘Monaro’: ‘whirring light’

p.26, ‘absorbs’: ‘tiny lights / from the other side’

p.32, ‘that all’: ‘Lightly institutionalised behaviours’

p.36, ‘happy days’: ‘happy days, bold geraniums’ and ‘Nothing we want any more […]’

p.63, ‘Lawyers, Mystics’: ‘time and language’

p.60, ‘cones’: ‘Any idea how many layers […]’ and ‘cones and bollards have been […]’

p.71, ‘Those were’: ‘A chorus / of manouevres charges past […]’

p.17, ‘Sideways’: ‘lovely and runaway’

p.70, ‘It could’: ‘rocky inter-tidal zone’

p.49, ‘Greetings from’: ‘a paddock with thin mist […]’

p.25, ‘crool forchin’: ‘a record of our national selves’

p.49, ‘Greetings from’: ‘Now a computer-generated coastline […]’

p.26, ‘absorbs’: ‘way below the slipstream […]’

p.15, ‘Really’: ‘Things / in their everyday zones’

p.68, ‘Now’: ‘No doubt the open country […]’

p.46, ‘Nothing Grows’: ‘The world is a weird village […]’

p.44, ‘Roadside Grass’: ‘return’ and ‘overturn’

p.35, ‘there was’: ‘the source code whose portability […]’

- Clark Coolidge in Paul Carroll (ed.), The Young American Poets. Chicago: Follett, 1968. 149. ↩

- Gertrude Stein, ‘How Writing is Written’ in How Writing is Written: Volume Two of the Previously Uncollected Writings of Gertrude Stein, ed. Robert Haas. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow, 1974. 158. ↩

- John Tranter, The Alphabet Murders: Notes from Work in Progress. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1976 (A&R Poets of the Month series, No.2). 36. ↩