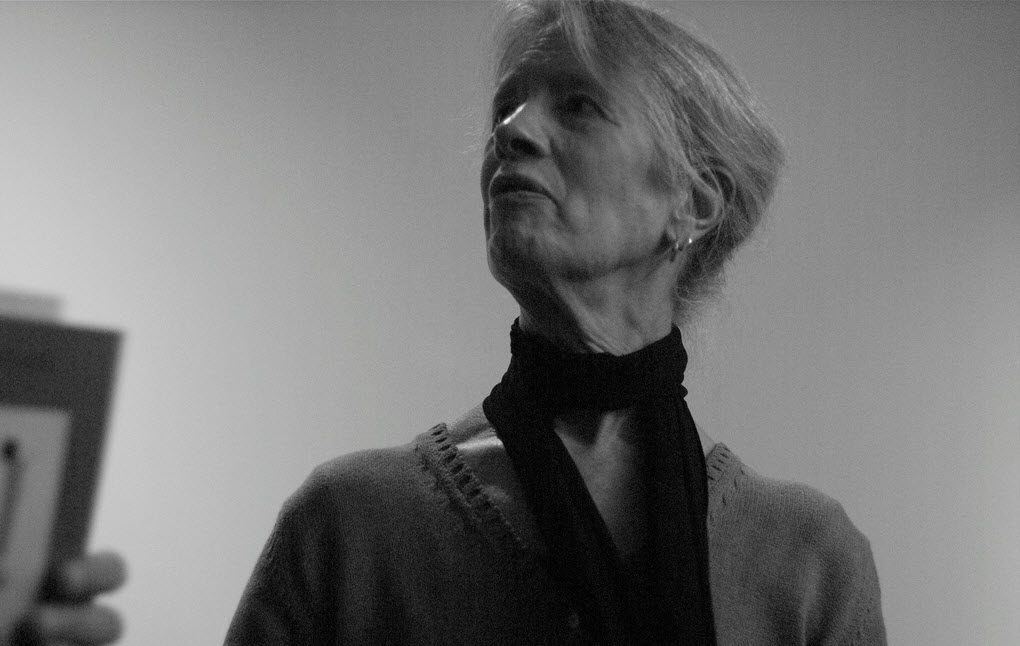

Image courtesy of Graybird Images

In July, 2014, the American poet Lyn Hejinian visited Australia to participate in two events – the ‘Women’s Writing and Environments: 2014 Contemporary Women’s Writing Association Conference’ at the State Library of Melbourne, where she headlined alongside fellow keynotes Alexis Wright, Chris Kraus and Deborah Bird Rose; and ‘Experimental’ at the University of Sydney, where she appeared alongside Carla Harryman and Barrett Watten. She also visited the Poetry and Poetics Project within the Writing and Society Research Centre at Western Sydney University, where she gave a long poetry reading followed by a conversation with poet and musician Kate Fagan. The discussion focused on several of Hejinian’s most recent works including The Book of a Thousand Eyes (Omnidawn, 2012), Saga/Circus (Omnidawn, 2008) and The Grand Piano: An Experiment in Collective Autobiography (Mode A/This Press, 2010).

Listen to the full poetry reading and interview (9 July, 2014) at the WSU Poetry and Poetics Digital Archive.

Kate Fagan: I’m so pleased we’ve all had a chance to experience Lyn reading. One of the comments that came back often during morning tea was that people felt they were listening to you for five or ten minutes, when in fact you’d been with us for an hour. Such was the temporal warp generated so beautifully by those incredible readings. I’m now going to say a little more in a formal sense about Lyn.

Lyn Hejinian is a well-published poet with many books to her name. She is the John F Hotchkis Chair of Literature at the University of Berkeley in California. She is an experienced, well-known and respected translator. We have a strong group of translators here today, including Peter Boyle. Lyn is a publisher; she’s published small chapbooks in letterpress editions through the Tuumba Press imprint, but also more recently, a kind of reiteration of that through Atelos Press with Travis Ortiz. Atelos focuses on crossings between the poetic and the philosophical, and ideas of how a poetics can do the work of philosophy and poetry simultaneously. Lyn travelled extensively in Russia at a particular time of her career and forged a fascinating and productive relationship with innovative Russian poetry, from St Petersburg in particular. She was of course foundational to the early clustering of poetic excitement, intensity and crush that was, and is, the Language School of poetry.

I might pick up the conversation around The Book of a Thousand Eyes. This may be a little cheeky, but it’s partly because of a comment you made to me a couple of days ago, that ‘the music keeps getting better’.

Lyn Hejinian: That was a reference to my husband’s playing not mine!

KF: To me this is a book in which the music of your undertaking keeps getting better. And the stakes of the telling also keep getting better. I might talk about form and add a little footnote, and then hand over to Lyn. Some of us here have just attended a series of events [‘Women’s Writing and Environments’ and ‘Experimental’] in which Lyn both has been figuring highly, and very generous; she’s given two keynote conference addresses while here. The first was on the relationship between what Lyn calls the ‘over-signifying’ poetics of the Occupy Movement, very political and vital, and how that crossed with nineteenth century figurations of romance and revolution through the work of Victor Hugo, particularly the character Gavroche. The interpretation of poetical ditty in that paper was fabulous. Then Lyn moved to a discussion of contemporary allegory, something she is talking about in a new work called Wild Captioning. This generated a discussion about notions of the wild – the idea of the feral or the errant, the errant work that points to texts without pointing – and some vital issues about landscape, the pastoral, and also political undertaking. These are really great backgrounds to today’s conversation.

One thing that occurred to me was that poetic form itself has rarely been mentioned across the last week. I’ve heard almost no one say poetic form. What we’ve said is ‘the wild caption’, ‘the allegory’, ‘the challenge’, ‘the crush’. I’m interested here in where form has gone in a bigger discourse about innovation. We’ve heard words like ‘rhapsody’, ‘ekphrasis’, ‘aggregation’, ‘agglutination’. Yesterday someone talked about post-conceptualism, and Lyn you said: ‘I’m so glad we’re post that already … that form has moved on!’ So I guess I’m interested in the schooling or the discipline of what works into a kind of formal likeness, and in the way you radically resist that. Historically, politically, there’s an always-already to form now that is very exciting. So, that’s an entry to the next hour.

LH: I think that part of, or the beginning of, a response is the quite obvious one that will be familiar to most if not all of you, which is the way that in English language the term ‘form’ suggests something static that’s like the glass and then you fill it. The glass is the form and the water is the poetry, and you plop it into the glass and then you’ve got your poem. That’s the way that English language is – so noun based, and imagining the world as having a kind of fixity of givens of things in it. What’s much more productive I think is to imagine the term ‘form’ as synonymous with force. That a form is a kind of engine. And a number of people associated with Language Writing (as with the conceptualist, post-conceptualist, and of course many other schools and non-schools, anti-schools) think about what the work is going to look like, how you’re going to organise it.

Because the options are virtually limitless. And if you’ve got an impulse to get going – whether you know what you’re going to go about or not – it can be very useful to think of kinds of constraints, rules of writing that can tell you how to shape it. Those have been incredibly productive. The trick when launching into a new work is to think of a shape that in some way is going to further the project that you’re embarking on, rather than curtail it or ossify it, or misdirect it.

During the two conferences, the papers that I heard (and I heard a lot of them, all of them at Sydney and a quarter or more of them at Melbourne, because there were four sessions at a time and I couldn’t be at more than one at a time, not because I bailed for 75% of the time) were about theory, like philosophical, social, cultural forces that are in play at this moment. And I think that’s entirely justified – even though most of the people at the conferences were makers, creative writers, or were interested as readers in what is being made, like ‘how does this car work?’. Nonetheless, one of the themes that’s been recurrent and urgent is the fact that so many of us feel that we’re living in a time of terrific political, cultural, economic and environmental crisis. We’re in an emergency. So to talk about ‘how many stresses before you make a line break’ seems, at the moment, to be peripheral to the major conversation that needs to be engaged in. If we had a year, all in this room, occupying the building, then we could talk about all of these issues. And then we could also talk about how many stresses or beats in a line before the line break. Or we could argue about it. I think that’s one reason that form just didn’t come up. I could be completely wrong; but I think it wasn’t the thing of the moment.

The second thing that occurred to me as you were asking that question is what I have experienced as two impulses, now that I’m a ‘truly proper professor’ in a ‘truly proper academic situation’. And I really love it, and I love the kinds of scholarly critical work that my colleagues and students do. There’s a real draw to interpretation. I believe all creative writing is interpretive in some way. It makes inquiry, it’s investigative, it maps, it wonders, etcetera. But the academic is apt to want to categorise. Some of that can be interesting, but I think it’s terrifically dangerous. One of the things I keep thinking about is how to be an interpretative thinker who isn’t a terminal thinker, who doesn’t say: ‘we’re going to slot these four writers into the post-conceptualist school and these into the anti-lyric tradition and this little cluster over here is the epic narrators’. That’s just bogus. But you do see dissertations like that. So I think that’s a kind of canon formation or school formation that rhymes with poetic form, but I think does a similar disservice, toward a kind of ossifying. I don’t love categorising, but I do like the kinds of scholarly thinking going into archives, the kind of work that Ella [O’Keefe] does.