Image courtesy of The Operating System

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s poetry may feel to some as very abstract – perhaps to the point where one feels they cannot achieve what is considered to be a thorough or ‘correct’ understanding of the work.

What has come to light from my exchanges with Berssenbrugge is that there is no singular way to understand her work. Perhaps drawing lines around and across differences in understandings poses a bit of a problem (not necessarily one to be solved as such, but to be thought and written through) and only directs us back into a canonical way of thinking, instead of propelling us forward and out.

Berssenbrugge speaks to me about her ongoing relationship with language and understanding(s), and why she chooses to view writing as a service, as a growing source of non-material provisions. How does a thought live on after we think it? And similarly, what happens to a line in a poem once it is written, read, processed?

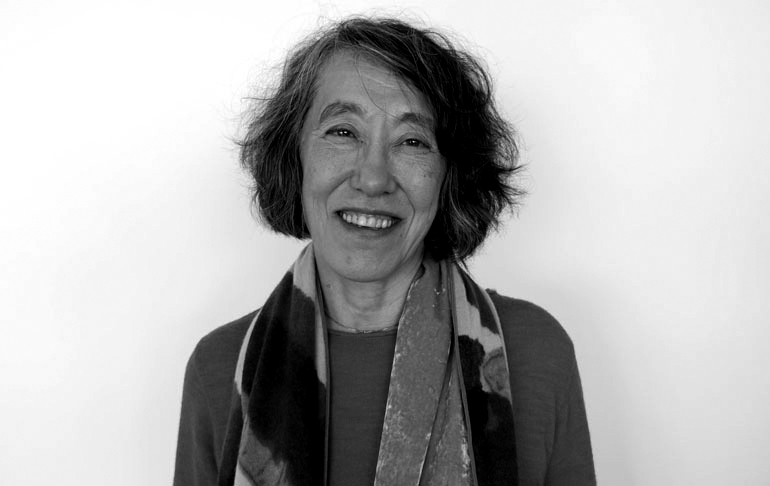

Speaking to her is an overwhelmingly sensorial experience, despite the fact that we are listening and responding to each other through machines. Her verbal expression is quite similar to that of her poetry; the mundane is made metaphysical, theoretical made personal. Berssenbrugge’s generosity is profound, evident from the time she takes to answer my questions, and her answers are at once secure yet humble, open to being shaken a little bit.

After hanging up on our last video call, I felt many things including a kind of grief.

I also felt incredibly grateful that Mei-mei Berssenbrugge accepted to converse with me. I would like to make explicit that what is being published here is less than a sixth of our full conversations. She afforded me the privilege of being allowed into her material home – as she carried me via laptop into the vast landscapes of New Mexico, across her metres-long writing table, and along her walls of bookshelves – but most generously, she welcomed me into her poetic practice and her branches of thinking, which feel almost greater than the vistas of Albuquerque she showed me from her balcony.

My conversations with Berssenbrugge also created a sense of relief. She explained, in a way that was not explanatory at all but more like an invitation, that poetry and one’s understanding of it is not singular – out of necessity, it cannot be. It occupies a state so multiple that its plurality cannot perhaps even be intellectualised in a way that is fathomable, much like this very sentence is attempting to do. To understand a poem, any poem, is an ongoing process, one where diversion and distraction and delay are perhaps requisite for it to continue moving.

I view Berssenbrugge’s writing as working towards fostering a non-binaristic mode of thinking. Popular couplings such as thought / feeling and poetry / theory exist as spectrums in her mind, and taking into account the work she has made throughout her decades as a writer, she has always been a spectrum thinker, or indeed a spectrum feeler. In her poem ‘Karmic Trace’ from Hello, the Roses (New Directions, 2013), she closes it with the line: ‘I feel joy, but it is relative.’

Chi Tran:

An experience is not one experience. I go over it again and again, as it assimilates in me. Repeating becomes more like an associative process. (excerpt from ‘Winter Whites’, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge)

In preparing for this interview, I asked my friend what makes him gravitate toward the artists that he does, and after citing the wonderful Leslie Scalapino, he said he likes people ‘who don’t really make sense.’ And I related to his response in the way that I find your work at once very challenging but very generous in its attention to time and its attention to change. As a reader of your work, I don’t think I understand it, but my failure to do so does not feel collapsible nor does it feel alienating; in fact, it feels fruitful. As a poet, how do you relate to these ideas of sense-making and understanding?

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge: I think all time is simultaneous, so that remembering is more of a creative process, and so imagination plays a larger role in our perception of reality.

Remembering is progressive; an event that is amorphous can begin to radiate energy or comprehension to you, in your mental solar system or galaxy. So then remembering would be generative.

Each time you remember, it is from a different place and time, from a different point of view or aspect, so there is no repetition. When you remember an event, you are associating to a new event, rather than returning to an “original” event. So associating is creative, a larger range.

I like when memory becomes an iconic story. Like the story of my engagement or when our snake declared herself alpha over our little dog.

I often say that I have never understood a single poem. When I read a poem, I take it in as a whole. In the same way that I do not understand Schubert’s Sonata in D Minor I love so much.

Sense is awareness. Understanding, comprehension, is a ‘grasp’, more fixed.

In this poem [‘Winter Whites’], remembering, associating, helps to construct the diaphanous energetic wholeness of all things. For me, the wholeness of all things is always the sense. (The charge of emotion with respect to association becomes the atmosphere.)

CT: Thank you for your answer to my first question. I am really interested in talking to you about this idea of ‘understanding’.

MB: Yes. Even though I studied poetry in school and I have a graduate degree in poetry, I don’t think I’ve ever understood a single poem in my life. I think there’s an argument to a poem, and then there’s the energetic matrix of a poem. And I think it’s the argument that I don’t necessarily understand in poetry.

CT: What do you mean by an energetic matrix?

MB: I think of a poem as an energetic whole, because the way I reach an expression of energy is through language. I definitely think about the so-called idea or meaning of a poem, but for me, it is more about keeping the energy high. I also want to mention that when I write a poem, I often have no idea of what I’ve said. I make assemblages of notes and put them together, but it’s at the unconscious level that composition occurs, and I think there are more profound gestalts of understanding to be found that way. So I am not somebody who thinks complex thoughts by my will; I find them. A lot of people now say that there are more neurons in the heart than there are in the brain.