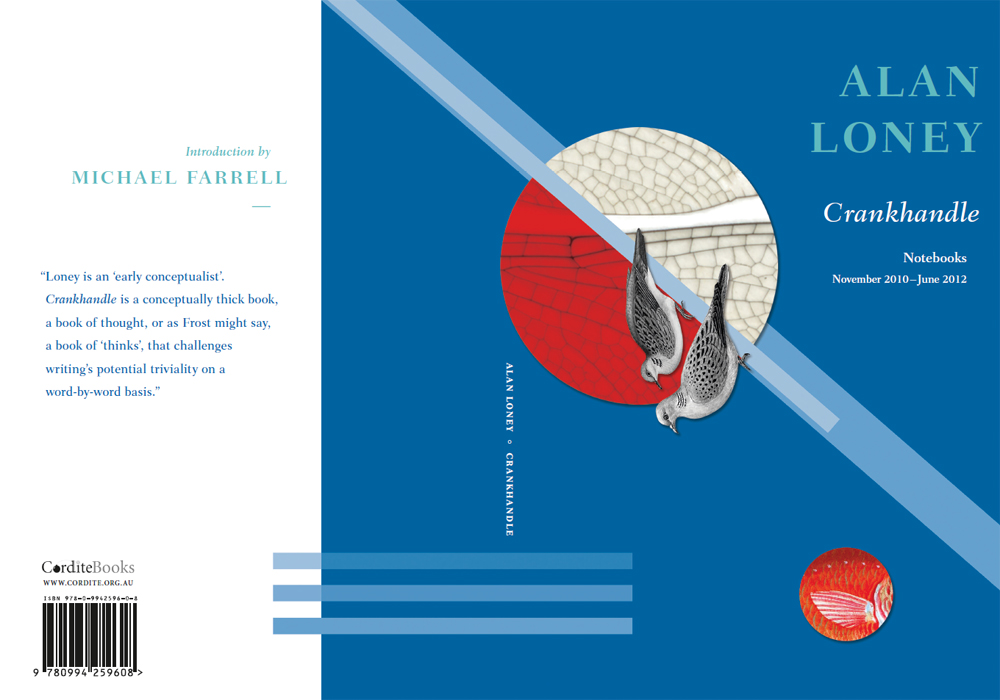

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

Since moving from New Zealand to Australia back in 2001, Alan Loney has carried on a prolific, internationally recognised career in Melbourne. Crankhandle, Loney’s latest published work, follows on from 2014’s chapbook collaboration with Max Gimblett, eMailing flowers to Mondrian, and the books from Five Islands Press, Nowhere To Go (2007) and Fragmenta Nova (2005). Borrowing his contemporary Laurie Duggan’s term, Loney can be read as a ‘late objectivist’: worrying at that particular American formal legacy, with its attendant philosophical and ethical concerns.

In Fragmenta Nova Loney writes, ‘“Poetry” is too small a word for the cry that issues from the mouth. “Form” is too small a word for the shapeliness of words upon the page’ (‘Poiesis’). This quote points to the uncontained – and affective – quality of much of Loney’s work, as well as to his attention to visual design. This is not an aesthetic concern only, but one that enables reading: lucid aspect as well as articulated ‘cry’. Elsewhere, Loney has characterised his writing in successive modes as a practice uninterested in ‘perfect individual poems’: ‘If the poem’s an imperfect take on the world or even part of it, better to be crisp about it, and treat writing as unfinished and unfinishable business. So, adopt a framework, write for a while, then stop. It isn’t, of course, quite as simple as that’. Perhaps then, Loney is an early conceptualist. Crankhandle is a conceptually thick book, a book of thought, or as Frost might say, a book of ‘thinks’, which challenges writing’s potential triviality on a word-by-word basis.

A writing motto appears about a quarter of the way through:

write as if you had never written anything before

The word ‘crankhandle’ suggests revving up but also letting go: write, then think. In a 1997 interview, Martin Harrison said, ‘I think the age now is of living systems.’ Loney, in the book’s epigraph, refers to antiquity’s knowledge of the writing system. Writing is part of that living system: as both noun and verb. Traces of Greek mythology recur in this book – as do other pre-contemporary traces – yet these are not necessarily allusions, but an attempt to find a place for a history of writing. Writing as an activity of the body, which may or may not end up in a book. Like a beach, ‘a book is a public place’.

Crankhandle contains double or parallel texts that recall Anglo-Saxon or indigenous traditions, like the Maya, where translation is what produces poetry.

wide foam-veined wave birdless foam-marbled wave air

Though the desire for words in space is cited, this space both includes and extends beyond the mind: ‘dragonflies above / goldfish below’; ‘dead possum / on the nature-strip’. An Australian source is suggested for writing, voicing and quoting: ‘but with lyrebirds about / you wouldn’t know / who’s talking’.

Crankhandle is a late book in that the sense of both individual and social self recedes: ‘the “my” of “my library” / where did it go’; ‘no longer care / what others think poets ought / to be doing’. Signifying closure, Orpheus as spider descends onto the last page of the notebook: the poem’s over. Or perhaps, in our minds,

not

quite

yet.