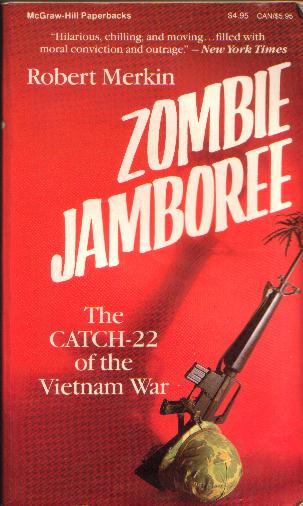

Robert Merkin is a writer and journalist based in Masschusetts, USA. He is the author of two books: “Zombie Jamboree” (1985, left) deals with his life as a draftee in the US military during the Vietnam war, while “The South Florida Book of the Dead” chronicles crime scenes he witnessed as a journalist in Florida in the 1980s. We contacted Robert via e-mail, requesting an interview. What follows is his four-part (mostly unprompted) response, a meditation in prose on all things Zombie, from voodoo to World War Two. As Merkin writes: “I would write my zombie thoughts in poetry, but I am, as Faulkner called all novelists, a failed poet, and I just lazily grew more comfortable with prose -”

Robert Merkin is a writer and journalist based in Masschusetts, USA. He is the author of two books: “Zombie Jamboree” (1985, left) deals with his life as a draftee in the US military during the Vietnam war, while “The South Florida Book of the Dead” chronicles crime scenes he witnessed as a journalist in Florida in the 1980s. We contacted Robert via e-mail, requesting an interview. What follows is his four-part (mostly unprompted) response, a meditation in prose on all things Zombie, from voodoo to World War Two. As Merkin writes: “I would write my zombie thoughts in poetry, but I am, as Faulkner called all novelists, a failed poet, and I just lazily grew more comfortable with prose -”

RM: As a little introduction to me and zombies, my head has always been filled with popular music, novelty songs of the moment, and one of them that had always stuck with me, from around 1960, was an American version of a Trinidadian Calypso song called “Zombie Jamboree” (or “Back to Back”) by Conrad Eugene Mauge, Jr, who performed as Lord Invader. He was a very big Calypso star with quite a few recordings. The line that always grabbed me was:

Well we don't give a damn 'cause we done dead already

[I liked] the idea and the image of partying and merrymaking without any “momento mori” restraint. This was actually a rather shocking image to me in the midst of a very serious, puritanical, Protestant-ethic sort of upbringing. Five or six years later America would start to see lots more anti-puritanical unrestrained merrymaking; “ZJ” struck me at the time as quite revolutionary, even threatening, but it was always candy-coated as a comic song.

Zombie acne.

|

I try to write seriously about serious themes, but I think I'm by nature a failure as a conveyer of tragedy; the funny and the comic aspects even of the ghastly catastrophes of history just keep creeping into the way I think of the world and the way I write about it. “Zombie Jamboree” was from its birth intended as a funny and very disrespectful song about life beyond death, and when I started to write about the experience of soldiers during Vietnam, “ZJ” popped back into my mind as an apt theme — a screwy sort of song that would keep the whole miserable experience from being entirely tragic or entirely maudlin, because the main characters just couldn't ever quite bring themselves to cooperate with an entirely tragic and maudlin view of or program for the world.

I don't know squat about the authentic roots of Caribbean zombie culture, the roots that are deeper than just entertaining bogeyman horror stories. If it's real zombies you're after, I suspect Haiti is where you want to start. Voodoo seems to be the Creole term for this belief system, Santeria the Caribbean Spanish term. Haitian politics has always had a very heavily integrated supernatural element in it, and a great deal of premature death.

Most of what we get about zombies is of the Hollywood variety, and so of dubious authenticity. My wife taught college English in the Cayman Islands for a few years. The Caymans are still a British colony, and historically trace to settlement by Cromwell's troops. If Caymanian Customs catch you with any kind of voodoo or Santeria or New Age mysticism or witchcraft, they toss you right back on the plane or onto your cruise ship. So don't go to the Caymans looking for zombies; zombies are forbidden from entering the Caymans.

I suspect African slaves kept alive certain themes of their religion as a buffer to keep themselves from being entirely subsumed by the Christianity of their conquerers. The Resurrection and Eternal Life are powerful and seductive promises; zombies promise believers things along much the same line, but in a form threatening, hostile and resistant to the new religion of their slavers.

But nobody needs to actually know much about actual zombies or zombie culture to wonder why it's such a compelling myth. Well — Christianity or not, no real person of flesh and blood wants to die, and I think we do a wonderfully lousy job of accepting death; we think it's shitty that our friends and lovers die, and we think it's triply shitty that things try to make us die before we're perfectly ready, and I can't imagine ever being perfectly ready to die.

Freud seems somewhere to have said that nobody ever truly believes he's going to die, and I think that's an accurate assessment about what we really think about death. I particularly love how little children — with the excuse that they don't truly understand death's tragedy and finality — make rude jokes about death and give Death the finger when they think he's not looking or can't harm them.

In the midst of death, we want to live so much and so desperately that there's bound to be some sloppy and disorderly spillover between the land of the living and the land of the dead, and zombies are one of those sloppy spillover realms that infect our imaginations. We secretly admire them, as ghastly as they seem, because they were told they were dead (as all of us will someday be told that we are dead), but they refuse to lie down and be quiet. We admire them because they were told absolutely to stop having sex, and they keep dancing and necking and screwing. They particularly horrify us by perverting and contaminating our official, quiet, orderly plans for cemeteries.

When we behave properly as survivors and mourners, and cooperate with proper funerals, a part of us feels we're giving up, surrendering, and agreeing to accept death and admit we have utterly no power against it. Zombies offer us a tiny window of fantasy in which, like holdout guerrillas in the jungle after a peace treaty we don't like, we don't have to surrender.

A zombie may be the embodiment of ghoulish perversity, but a zombie keeps living — or something near it, the state they call the Undead. That Undead is not the same as Alive — if it's the best you can manage, it's better than the official plan, which is Dead. Zombies are vertical, and they wiggle around a lot, and they make lots of noise. I imagine they strew trash around, too.

The promise of an afterlife with lots of very unruly parties I find particularly attractive. Already, in midlife, I find unruly parties to have grown scarcer and scarcer, and cannot fully understand why this has happened; it does not seem to have been by my desire. The nightime festivities of zombies look good to me.

Well, those are my thoughts on zombies tonight; I hope they please and perhaps interest you somewhat, and suggest questions. I would write my zombie thoughts in poetry, but I am, as Faulkner called all novelists, a failed poet, and just always lazily grew more comfortable with prose.