The Elephant in the Room

The Elephant in the Room

My plan to start teaching phonetics in my Korean English class actually germinated in Nepal. I began to notice signs similar to ones I had seen in Korea, toting the English language as a kind of educational panacea. I found myself wondering if the modern world was engaged in a cultural war, an effort to arm itself with my mother tongue. A policy of Mutually Assured Comprehension. Aware of my role in this cultural siege I decided I would make better use of my classroom time to teach things the Korean syllabus was not imparting in regular class time – word pronunciation, aural recognition of key words and English inflection.

It began well. The first week I taught syllables and played a classroom game where students had to solve maths problems where the integers were the number of syllables in a sentence. The next week I tried to teach word stress but had greater problems as there are so many exceptions to English stress patterns. The third week I had gotten to inflection but was facing real resistance from the kids.

One student asked me,“Teacher? (pointing to sheet) Last week?”

“Pardon?”

“Syl-la-bles. Last week? Syllables?”

If the kid had aced the sheet I would have understood his frustration. Problem was, he’d gotten half of the questions wrong. The final straw came when walking back from one of these unsuccessful classes.

My head was down, I was obviously frustrated and my co-teacher said to me,“I think this class is too difficult for the students.”

“Yes, but I think it is good material. I just need to make the subject easier to understand.”

“I think maybe you should just entertain the students. This subject is too hard.”

In the hopes of representing myself as an anything-but-unbiased-reporter I will quote verbatim the Facebook status update that immediately followed.

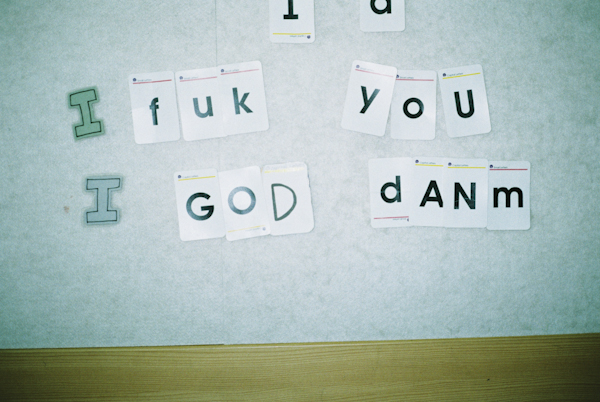

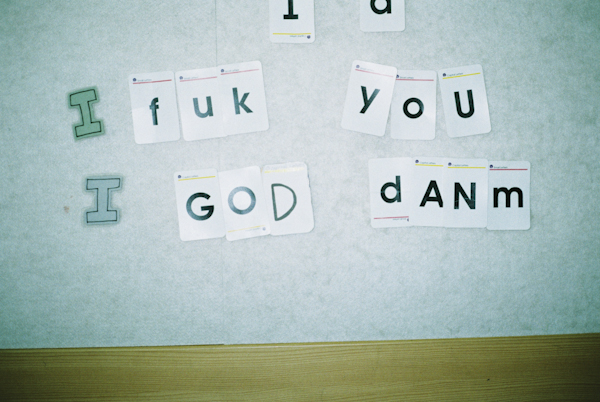

Daniel East is sick of DANCING LIKE A F—ING MONKEY! Dance monkey DANCE! Speak your goddamn monkey tongue. Play for our children. Ornament our school. Caper, smile, be our f—ing fool.

Playing the Race Card

I thought I knew what racism was. I had by turns been indoctrinated (by a grandfather who had fought against the Japanese in WW2), learned its dangers and ugliness (after an embarrassing display in primary school), read about the critical discourse surrounding it (a modest amount of Post-colonialism and Frantz Fanon at university) and finally thought I understood its pervasive, alien character (when I witnessed the extreme racial segregation between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians in Broome). But these were abstract, intellectual definitions – nothing prepared me for being treated differently due to my race and more importantly, reacting against this racial identification by generalising the reaction of individuals as indicative of a racial group.

The more I have thought about this event the more ashamed I have grown of the Facebook outburst above. The “R” word lurks like a leviathan of the shimmering deep beneath the drunken exchanges of the ex-pat community. Many other teachers have expressed similar feelings to the one I expressed above – feelings of being ostracised, undervalued and demeaned by our staff and students. But are racially specific complaints racist if they are partially justified by typified behaviour?

What the Job is

In Korea the job of the foreign teacher is simply to be a foreigner. Every school is different but most waeguk teachers (waeguk literally translated is “foreigner” but can be more correctly translated as “not Korean”) will be required to devise their own class material – and their efforts will be supported in class by a Korean co-teacher whose job is limited to translating directions and enforcing discipline. When school events come along (carnivals, festivals, excursions) the foreign teacher will remain behind his desk when the school may be almost completely empty.

He or she will be asked to prepare for open classes that other schools from the district will attend. These schools will bring their own foreign teacher along. Far from being an opportunity for teachers to share advice or ideas, the lesson is prepared in uncharacteristic detail and often delivered in expensive-looking rooms the students and teachers rarely see – effectively rendering any feedback irrelevant because the class itself is uncharacteristic of any regular teaching practice. Even the students do not benefit from these forums as the host classes chosen are generally removed from their regular syllabus to drill the lesson over and over. It is not uncommon to see students answer questions before the teacher asks them.

Dissent in the Community

Amongst ex-pat teachers these outlandish open classes are the tip of the iceberg. Twice a semester Korean schools undergo a radical shift as students prepare for their exams. Teachers stay late drafting papers, students begin to wear their blazers and vests to school (even in the middle of summer) and the foreign teacher finds all his/her lessons cancelled, sometimes at the last minute, for days or weeks before. Patrick, a friend of mine who lives one subway stop along, has had no work for almost a fortnight.

Image: Jackson Eaton

Well, almost no work. His job is to arrive in the mornings and deliver the ‘English Address’ (unscripted, unprepared English phrases spoken over the intercom the entire school repeats) and one after-school English class a week. This after-school class is a rotation of the entire school’s Korean teachers who are encouraged by the principal to teach all their subjects (science, maths, art) in English. Patrick delivers English lessons to overworked Korean teachers many, many years his senior in a country where age difference is so far ingrained it forms a linguistically complex part of the grammar (only a decade ago it was almost unheard of for Koreans to make friends with anyone with a few years age difference).

Yet Patrick’s Korean co-teacher (the person in charge of handling his paperwork) told him that if the principal was not present in the class to let the teachers go. They are ‘too busy’ to spend time in his class. An awkward situation for all involved, made worse by the reactions of the Korean teachers. Patrick said the class behaved like his lower level students: they were hard to control, talked to each other when he was speaking and paid no attention to his lesson.“I tried to teach them Yesterday by The Beatles. I mean, it’s Paul McCartney, man. Paul McCartney.”

A Better Defence for Future Outbursts

In the replies to my Facebook status mentioned above, one friend commented: “You’re not a person anymore, you are just a useful interactive book”

The stages of culture shock are well documented on the Internet, so I feel no need to dwell on it here. But generally they form a three step model consisting of a ‘Honeymoon’, followed by a period of ‘Adjustment’ that (sometimes) culminates in ‘Integration’. I had hit that second stage and begun to exhibit frustration and anger – but it was the nature of my anger, and that damned elephant in the room that I began to dwell on. Was it Korea that had gotten to me, or the job?

After all, was it all that surprising that I was given no responsibility during the important exam period, given that my position is entirely transitory and my presence limited to the twelve months of my contract? Is it surprising, given the language barrier between the staff and myself (even the English teachers are not particularly confident or fluent) that they encourage me to teach easier lessons so I don’t get so agitated? (I noticed many of my teachers were consistently getting the stress and syllable questions wrong). And was it really that odd that my lack of responsibilities engendered a little hostility among my co-workers – that it bugged them when they were busily preparing tests and dealing with rowdy students that I was watching season after season of The Wire – and getting paid to do it?

In my opinion, it comes down to this: racism is not making cultural generalisations but believing them to be the root cause of all problems. During the “Syllable stress teaching nightmare” period I had one student who openly mocked me in class by repeating all my instructions in a high, bitter falsetto. But instead of thinking, “Damn middle schoolers” I thought, “Damn Koreans.” When I had a class that wouldn’t behave because my co-teacher didn’t show up for a lesson I didn’t think “God-damned fourteen year olds,” I thought, “God-damned Koreans.” The frustrations I felt were more indicative of general human jerkishness and not culturally engendered disrespect.

Although I’ve had moments of being treated differently due to my race (older Koreans not wanting to sit next to me, teenagers giving sarcastic high fives, a co-teacher laughing at a student who mocked me behind my back) it was not a balanced response to blame the culture as a whole. I’ve had kids who’ve practically gawped with excitement to see me on the street, who rush into the staff room to say hello, teachers who have sat with me at lunch and laughed with me as I struggle with Korean pronunciation. The cultural divide exists, it causes anxiety and anger but it is not the entire reason for my problems. In my own culture, faced with a difficult workplace I might hate someone, but never an entire race. Over here, choked by the inscrutable bureaucracy, I turned my anger on the Koreans I was educating and working with. Understandable, but deplorable.

So what to do? Personally I’ve decided to embrace my lack of responsibility within the school system. I’m going to teach my own childhood interests (dinosaurs and the solar system) and hope I manage to impart some of the same wonder these subjects held for me when I was that age. Until I get told I’m not doing my job correctly – and then I’ll have to adapt all over again.

Post-script: The Korean for ‘Burden’

As so often happens with this type of article, the perfect closing moment came after the article itself had been finished. Never one to tamper with chronology I will relate it here.

Our school recently lost the head of its English department, a very kind and co-operative teacher I knew as Susan (when speaking of her to another co-teacher she didn’t understand who I was talking about until I pointed her out. No one was familiar with her English name). She was replaced with another woman whose name I have forgotten and been too shy to ask for again (see how it goes both ways?). Seeing no one else in the staff room I asked her to lunch and she came with apologies for not asking me earlier.

Our conversation was making a good clip on subjects of immediate interest and her time abroad made her more comfortable and fluent with her English. So it was that we were discussing the 2010 kimchi price hike when two older Korean teachers came and sat a few seats down from us. One of the ladies leaned over and said something to my co-teacher and she smiled a little awkwardly, nodding in return. Knowing I usually don’t get a translation of what is said I didn’t ask – but she offered immediately.

“They say the English teacher is a burden.”

“Oh.” Pause. “For you?”

“For them. I think they are very scared of you. They have only elementary English.”

When I pressed her on this, she related her experience at university where she saw a foreigner for the first time and could not understand anything he (the lecturer) said. “I think many Koreans have a fear of foreigners.”

Connecting this in my head to the article, I began to ask what sort of material I could teach to help students overcome this fear of speaking.

“That is a very fundamental question.”

She leaned back a little and began to cover her mouth as she spoke.

“I think it is good for you to just teach anything to the students.”

“Anything at all?”

“Yes. It is good for them.”

“For them just to see and listen to me?”

“Yes. I think it will help them to listen. You are doing a very good job. I think you are a very good teacher.”

The conversation continued on as I ate my bap and bulgogi. Out of interest, I asked her what the Korean word for perilla (a herb similar to sesame leaf) is – she told me and now, less than fifteen minutes later, I have already forgotten it.