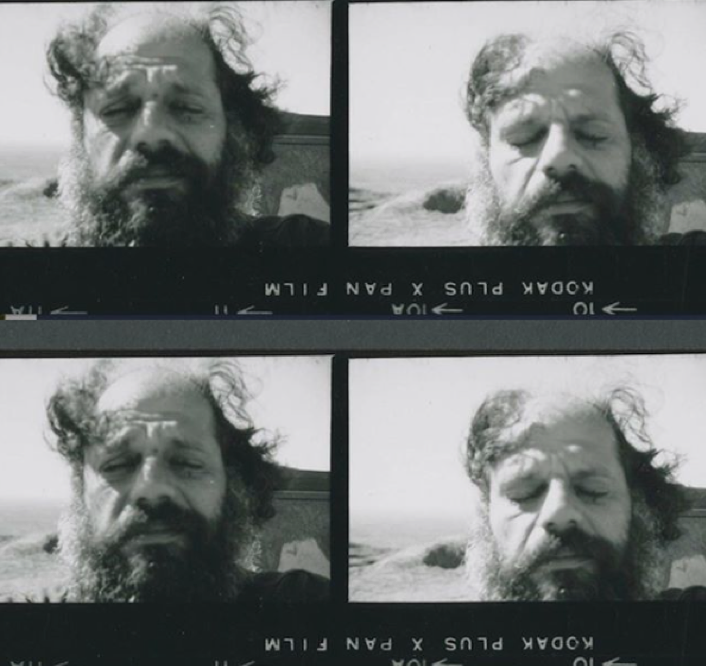

In ‘Ayers Rock Uluru Song’, by contrast, is written in heavily stressed, enstopped lines (a feature of the poem Ginsberg emphasises by marking each with a period). The lines are discreet syntactical units, and, while each new line echoes or adds information to the previous, they all present an otherwise self-contained image or idea. Ginsberg had taken psylocibin mushrooms before ascending Uluru, photographing himself as he peaked on the rock’s summit (fig. 1). Yet his poem about the ‘sandstone monolith’ appears sober and sedate when compared with the standard Ginsbergian line.

Figure 1: Contact sheet of self-portraits taken by Allen Ginsberg at Uluru (1972), Stanford Library Collections.

‘Ayers Rock Uluru Song’ can be compared to depictions by other poet-visitors, for instance, Gary Snyder’s ‘Uluru Wild Fig Song’ (1986), written during an Aboriginal Arts Council-funded teaching visit to Australia in 1981. Snyder’s poem describes his communion with the landscape, the isolated setting figured in sightseer’s terms as akin to a hippy wellness retreat:

Sit in the dust

take the clothes off.

feel it on the skin lay down.

roll around run sand through your hair.

an hour

bird calls through dreams.

now

you’re clean (Snyder, 92).

Snyder’s travelling companion in Australia, the Japanese Beat Nanao Sakaki, also wrote an Uluru poem: ‘Chant of a Rock’ (1981). In dramatic monologue, Sakaki adopts the position of the sacred landmark itself, speaking as Uluru to witness the tragedies of an encroaching Western history: ‘Remember Auschwitz in Australia / Remember Hiroshima in Australia / Remember a Shiny Rock in the dreamland!’ His poem is composed in the triadic or stepped-down line, a signature of American poetry, pioneered by William Carlos Williams in Paterson Book II (1948), The Desert Music (1954) and Journey to Love (1955):

So long, so long –

Forty thousand years

I waited for you (Sakaki, 106).

By refracting his imagination through the rock, Sakaki escapes the narrow earnestness of Snyder’s more conventional lyric. Sakaki’s poem leaves room for humour: in it, Sakaki speaking as Uluru expresses bemusement at settler Australia’s belated ‘discovery’ of its existence – ‘They call me a giant monolith of Tierra del Australia (…) / Now they call me treasure of commonwealth of Australia’ – and suggests an ironic slogan suitable for the Australian tourist board: ‘Please enter air-conditioned Australia / Please enjoy air-conditioned Australia’ (Sakaki, 106-7).

Differences aside, both ‘Uluru Wild Fig Song’ and ‘Chant of a Rock’ are nonetheless examples of the syntactically coherent, linguistically unadorned, metrically free verse, which had, since the 1960s, become the dominant poetic mode in American and increasingly world poetry. By contrast, Ginsberg’s ‘Ayers Rock Uluru Song’ attempts something very different. Consider this description of the poetics of Indigenous song cycles from Strehlow’s Songs of Central Australia: ‘(Arrernte couplets) tend to consist of two individual lines which, musically and rhythmically, stand in complementary relation to each other: the second line of the couplet is either identical in rhythm and construction with the first line, or it balances the first line antithetically or it rounds off the couplet with a rhythm of its own’ (Strehlow, 109-10). ‘Ayers Rock Uluru Song’ adheres closely to this couplet form, with lines seven and ten acting in triplet group with lines five and six, and eight and nine, respectively. ‘Each line contains a single idea’, writes Catherine Ellis of the Miniri/Langka cycle, accounting for the heavily end-stopped lines of Ginsberg’s poems (Ellis, 96). Snyder and Sakaki wrote about an Australian setting in recognisably American (or, in Sakaki’s case, American influenced) free verse; Ginsberg instead sought to emulate and personalise a distinctly Australian poetic form.