There are some books that carry you along a journey until your tears make it impossible to read. Films and television shows, too. Games evoke emotion in a similar way to non-interactive works, with some exceptions – the greatest difference being emotion facilitated through action. In this essay, I look at games and electronic literature that have triggered my emotions and reflect on how this was achieved. The poet, novelist, screenwriter, playwright and games writer will find similar rhetorical devices being applied in different ways.

What sort of emotions am I talking about? In his essay on emotion in film, film theorist Ed Tan speaks about the difference between what he describes as ‘artefact emotion’ and ‘fiction emotion’ (Tan). Artefact emotions are ‘non-empathetic’ and occur in response to sensory pleasures such as the appearance of the actors, costumes, scenery, and special effects. A viewer engaging in artefact-based emotions does not need to engage with the story at all. On the other hand, fiction emotions are ‘emphatic’; these are direct reactions to the story and empathy with the characters.

When we talk about emotions in games, the relationship between content and viewer shifts from empathy to embodiment of the self. Indeed, some game researchers talk about emotions that are not related to ‘cut-scenes’, the story or characters. Industry researcher Nicole Lazzaro, for instance, has observed what she calls four key types of fun outside of story:

Easy Fun (Novelty): curiosity from exploration, role-play, and creativity

Hard Fun (Challenge): fiero, the epic win, achieving a difficult goal

People Fun (Friendship): amusement from competition and cooperation

Serious Fun (Meaning): excitement from changing the player and their world

(Lazzaro)

Likewise, in his book on ‘game feel’, Steve Swink talks about game feel being made up of three parts: real-time control, simulated space, and polish (Swink 2009). But this piece isn’t about emotions related to achievement, or spectacle. Instead, this piece explores emotions facilitated by a relationship with a story and its characters, and the player’s role in that experience. From a writing perspective, it is a shift from writing the journey of a hero readers will (hopefully) empathise with, to facilitating the emotional journey of the players. How does this happen?

Pic 1: Screenshot of Journey

Pic 1: Screenshot of Journey

An award-winning game that is lauded for its emotional experience is That Game Company’s Journey. I played Journey as a single-player and, although it is designed to be multi-player, I went through an emotional experience. As a robed figure, I slid through the sparse desert and mountains. At times I felt peace, at times I felt hope, at times I felt lost, and there were times I felt I’d never, ever, make it. This wasn’t frustration over a too-difficult puzzle. Instead, it was frustration or fear for myself. How did this happen?

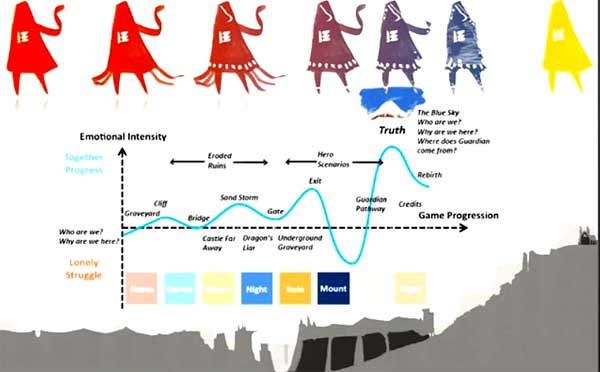

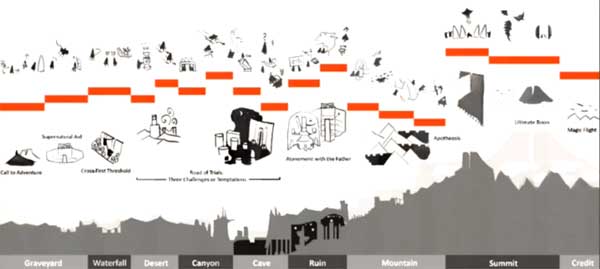

In his Game Developers Conference talk this year, Jenova Chen, director of Journey, described how, during development, he discovered that his design of the player journey correlated with Joseph Campbell’s ‘hero’s journey’ (Chen 2013). He had designed the player journey, for instance, to be about stages of life, with varying emotional intensity (see Pic 2). Chen further notes how the stages of life, artwork and geographic terrain all fit within the slow rise, extreme downturn and ultimate catharsis of the ending (see Pics 3 and 4).

Pic 2: Game design and Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey

Pic 2: Game design and Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey

Pic 3: Character, emotional and geographic journey

Pic 3: Character, emotional and geographic journey

Pic 4: Character, art and geographic journey

Pic 4: Character, art and geographic journey

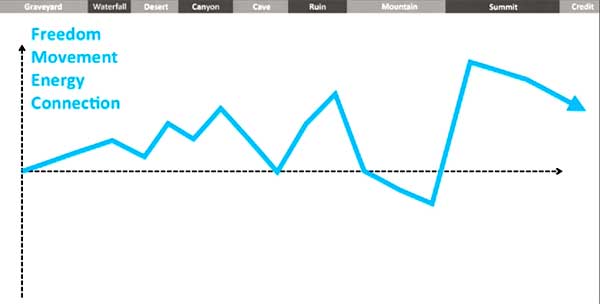

Chen explains how it was the gameplay aspect that needed extra time to refine. One can use art, sound and story triggers to facilitate an emotional journey, but how can player actions support the intended stages of feeling? What Chen and the team did was heighten and reduce certain abilities according to what stage the player was intended to be at. Freedom, movement, energy and connection were all either encouraged or restricted (see Pics 5 and 6).

Pic 5: Gameplay actions and the player journey

Pic 5: Gameplay actions and the player journey

Pic 6: Gameplay journey

Pic 6: Gameplay journey

A big part of the emotional experience of Journey, for me, was due to the game being designed to encourage intuition. There weren’t a great many things for me to do as a robed figure in a sparse desert setting. I could venture off into any direction (at times) and focus on sliding over the sand. I found non-human friends who guided me around. I discovered how to make things happen in simple ways, and these kept moving me towards a distant mountain. But importantly I felt as though I was using my instincts. I felt as I was using things I already knew. The abilities of my avatar have some overlap with my abilities. I know how to run, walk, slide and jump. Granted, I don’t know how to fly, but I understand the concept (and sure have flown in my dreams).

All of this means that more of me can come into the experience. I’m not busy learning and doing things, so there isn’t a big cognitive load. This gives me time to project my memories and life onto the game. It allows me a deep-dive into myself – to contemplate. The setting triggers memories and feelings. The tasks and images along the way trigger thoughts and memories of my own life journey.

Games like Journey have been accused of not being games. Veteran game designer and educator Chris Bateman explains that they don’t have an ‘agency aesthetic, a way of enjoying play that focuses on the player’s ability to enact meaningful change in the fictional world of the game,’ which is a feature that is considered ‘the sine qua non of game aesthetics and hence a necessary condition of “gamehood”’ (Bateman 2012). Bateman’s response to this is the notion of ‘thin play’ (ibid.); he juxtaposes the busy activity of a first-person shooter, where a player runs around navigating the space, hiding, attacking, and reloading, with the spatial navigation of art games like Dan Pinchbeck and Robert Briscoe’s Dear Esther and Journey. Some critics claim that if you take away all that activity, you take away agency – and therefore its distinguishing feature as a game. Bateman argues that the process of navigating decision points are still a type of play; it is just thin. Even further, these sparse abilities become more important and ‘high in expressive value.’