For me, the notion of ‘thin play’ resonates as a descriptor because it involves a receding of the designer at some point too. The quietness of Dear Esther and Journey facilitate projection through the removal of things. The more you remove, the more people project themselves. Talking with Cordite Poetry Review editor, Kent MacCarter, there are parallels with poetry as well. The slenderness, MacCarter reflects, demands a reader to insert themselves into the open spaces made available. Indeed, game developer Brian Upton’s comments in Bateman’s post furthers this idea:

The thing is, I think our critical assumptions about interactivity often warp our ability to understand place spaces. A lot of times, the interesting part of a play experience involves long contemplative chains. The interactive bit is limited to a minor bit of business to keep the contemplative play ticking along. When I was designing tactical shooters we’d often create levels with safe observation points, locations where the player could pause and observe and think about what lay ahead and what he was going to do. The play that took place at these moments wasn’t interactive, but it was definitely engaging.

When a play space is packed with lots of immediate opportunities to act (or interact) there’s no room left for contemplative play. The cognitive load is too great. If you’re always worrying about tactics, there’s no room to think about strategy, or more importantly, meaning.

(ibid.)

Simulating mental states

The removal of agency can also effectively simulate or induce mental states that trigger emotions. In many works, game and non-game, structure is manipulated to give the reader or player the direct experience of emotions. Consider for instance the Women’s Aid television commercial that attempts to communicate the experiences of shock, boundary-transgression, loneliness and fear in domestic violence (trigger warning for some).

Interactive works exercise the same techniques, manipulating and restricting what the player can do to simulate the direct experience of a mental and emotional state. Christine Wilks’ e-lit Rememori, for instance, is a ‘degenerative memory game and playable poem that grapples with the effects of dementia on an intimate circle of characters’. In this work, through the clever use of the user interface, music, art, and design, I’m subtly put into the position of struggling with my memory. In just a few moments, by changing locations, systems, timing, and fading the interface, I feel moments of frustration, fear and confusion due to the forced failure in a memory game.

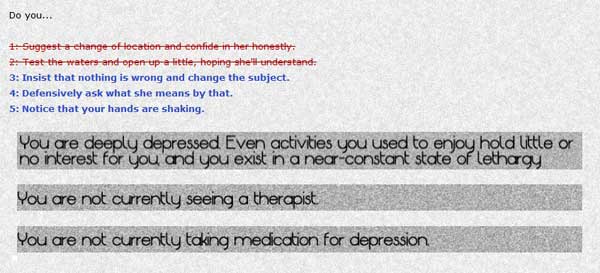

Likewise, Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey and Issac Shankler’s Depression Quest enables you to play as someone living with depression. Its aim is to ‘show other sufferers of depression that they are not alone in their feelings, and to illustrate to people who may not understand the illness the depths of what it can do to people.’

Pic 7: Image from Depression Quest by Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey, and Issac Shankler

Pic 7: Image from Depression Quest by Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey, and Issac Shankler

Artist Maddox Pratt discusses Depression Quest in reference to rhetorical devices employed to communicate madness:

Traditional narrative form seeks to make sense of the senseless, creating order of the fragmentation and giving voice to what was or still is silent. When shaped into the narrative form, madness loses its very character and by ‘assuming an appearance of reason’ becomes ‘contrary to itself’ (Foucault, 1988 107).

(Pratt 2013)

How does a writer communicate madness? Pratt refers to Brendan Stone’s contention that this occurs when ‘writing without power’ (Stone 2004, p. 23).

Stone interprets writing/speaking without power as speech which ‘does not attempt to master the traumatic event; does not attempt to make that which is aporetic – intrinsically full of doubt – into something that can be fully known or understood’ (2004, p. 23). Writing without power is writing which respects the alterity of both the writer and the experience while ‘narrative mastery’ seeks to destroy it through codification, delimitation, and explanation. These actions may give the author (and the reader) a sense of momentary security and power over the experience through making it known, but through the narrative reshaping the experience is changed and may no longer be recognisable.

(Pratt 2013)

While the author argues that Depression Quest does fall into ‘narrative mastery’, the observation is an important one. We have to break structures and systems to communicate certain mental states and emotions. Indeed, certain structures and systems can only communicate certain mental states and emotions. In the next section I look at more ways systems can influence emotions.

Choice and emotion

Another way I experience emotion is through the nature of the choices I’m given. Many years ago, game design veteran Chris Crawford said that choices should be evenly weighted – there should be ‘a large set of dramatically significant, closely balanced choices for the player’ (Crawford). There shouldn’t be one option that is right or better than the others. The game One Choice by Awkward Silence Games displays this edict well. In One Choice, you’re a scientist who, along with your team, has accidentally created a pathogen that is killing all living cells on Earth. The game takes place in the last six days on Earth. You make choices about how to spend these last few days: spend time with your family, work on a cure, or go nuts? I kept being offered these options, and it wasn’t cut and dry for me. I would make a decision, and then I would feel guilty or think that another option was better for me and try again. Either way, whatever I did, someone lost with every decision I made, and I didn’t get any second chances.

Pic 8: Screenshot from One Chance by Awkward Silence Games

Pic 8: Screenshot from One Chance by Awkward Silence Games

Another game, Immor Tall by Pixelante, had me experience a similar quandary; however, the decision is less overt. You play an alien that has just landed on Earth. A little girl discovers you, and you travel through the town together. With each moment, your shape changes, transforming you from a dob of black to a tall blob that towers over the girl. Being an alien, you are of course attacked by the military. I felt misunderstood. There was no reason to attack me. But the big moment for me was when I decided to run away from the little girl. I ran because I didn’t want the little girl, my friend, to be hurt by the military attacks aimed at me. She didn’t understand why, and cried at my rejection of her. All of this with no words – just beautiful visual design, music and interaction engagement.

Pic 9: Screenshot of Immor Tall by Pixelante

Pic 9: Screenshot of Immor Tall by Pixelante

What stood out for me, with both these works (and others), is that my choices had two key qualities to them. One: all of my options involved a loss of some kind, a sacrifice. Two: because all my options involved a loss, my options were instead about what I value. So the decisions weren’t about right or wrong, or which is not as bad. Instead, my decisions were about who I am. Do I value my close relationships more than my sense of duty to the world? Do I value companionship over martyrdom? I was acting on myself in these choices, or at least discovering myself in them.