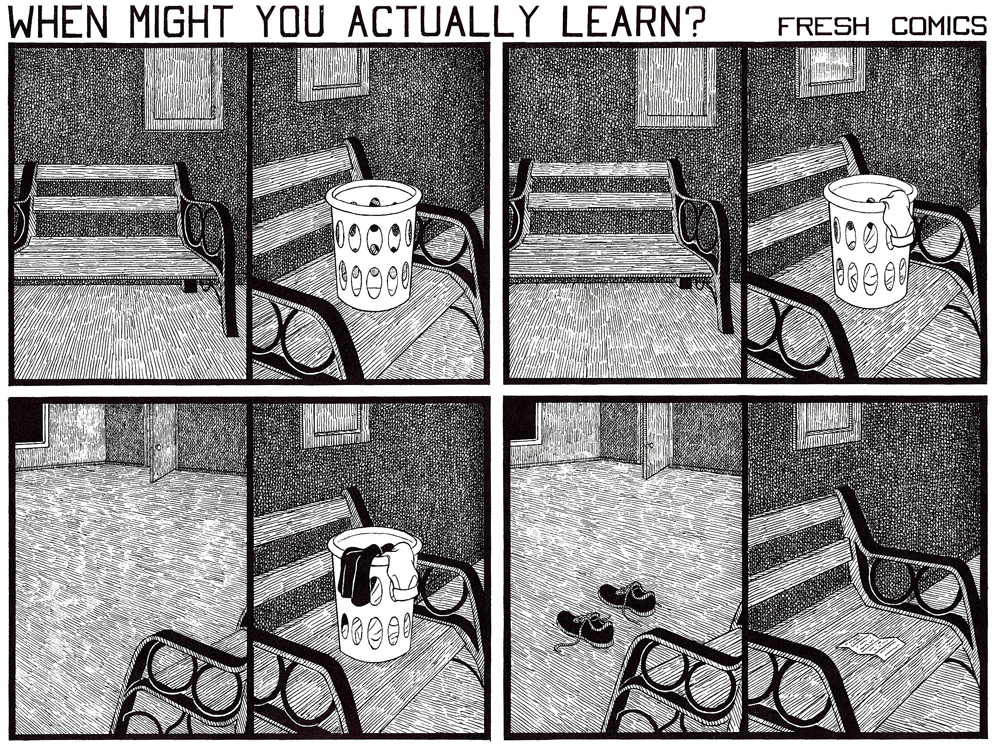

As in Madden’s comics poetry, repetition, rhyme and rhythm also feature in John Hankiewicz’s collection of ten short comics, ASTHMA (2006). The second strip, ‘AMATEUR COMICS’ is void of verbal components, except for the questions that seemingly ‘caption’ each episode. These captions are not narrative in a traditional sense, nor do they explain the images, instead Hankiewicz states that he ‘rhymes’ each image with the one that precedes it.1 Every page in ‘AMATEUR COMICS’ features four larger panels and, within them, two smaller frames that operate like countermeasured couplets. In the couplet ‘WHAT HAD YOU BETTER FEEL?’ the protagonist appears trapped in a realm of boredom. The first ‘line’ of panels shows him seated and reading a letter, contrasted with a seat on which sits a bottle of body cream. In the bottom left corner the protagonist ponders his hand, while in the panel beside he has vanished and a broken table leg rests against the chair. In the panel he sits hands crossed, staring into space. This scene is countered by the final frame of a completely empty chair, a power cord unplugged beneath it. Again in the final episode ‘WHEN MIGHT YOU ACTUALLY LEARN?’ the protagonist has disappeared, the only clues are a clothes basket, shoes, and in the right corner, the repeated symbol of the note that featured in the very first panel. The disappearance places greater significance on the note as the audience is left to wonder about the potentially infinite cycles and couplets of the comic.

Like Hankiewicz, Michael Farrell’s comics poetry collection BREAK ME OUCH (BMO) (2006) features a protagonist that morphs and disappears as well as visual-verbal couplets that create poetic rhythm throughout the collection. According to Farrell, rhythm, imagery and personae are the points of connection between comics and poetry …

there is a rhythm to comics based on frames that I exploited in a toy keyboard kind of way […] Poems are said to ‘have’ imagery, to be made of images, a way of reading that denies language as such. In comics this is separated. The imagistic quality of comics language is both underplayed (i.e relatively redundant) and diverted from; using explicit (i.e visual) imagery in BREAK ME OUCH allowed me to parallel, depart and play with that aspect.2

Imagery within BMO is simultaneously visual and verbal, visible and invisible. Through the use of negative spaces, Farrell pushes the perception of the invisible, amplifying the silence until it surrounds the poem like static or white noise. These gaps or gutters operate as visual caesuras, increasing the syntactical tension and opportunity to countermeasure segments. This spatial experimentation, combined with the constant use of handwritten, capitalised typography, moves his comics poetry towards a kind of ‘visual equality’ not found in traditional print poetry.3 The concept of visual equality can be applied to readings of BMO as the panels can be read as equal rather than sequentially ordered. Employing segmentivity, visual-verbal components can be understood in both linear and non-linear ways, as demonstrated in Farrell’s strip ‘MORT GUERRE’ where ‘ROMANTIC OPPORTUNITY’ may be paired with ‘TO BE MOVED IS ALL GONE’, or ‘TO CREATE’, ‘THE FORCE OF THE WORD REMAINS’. Through segmentivity, the final line ‘IN THE END’ can be connected to both the title reference of those fallen in war, and the ‘ROMANTIC OPPORTUNITY’ of metamorphosis and alchemic transformation. Again, in the strip ‘CLOUD’, the protagonist personifies metaphor, mutating into a bird that eclipses a sun, the same sun that is fashioned from the figure’s head. ‘CLOUD’, like several of the strips that follow, is also void of verbal components, yet Farrell establishes poetic rhythm by arranging each panel to mimic enjambed lines. These experiments in ‘visual equality’ further expose the potential for comics poetry to operate beyond narrative and sequential boundaries as segments are apprehended simultaneously and without absolute sequence.

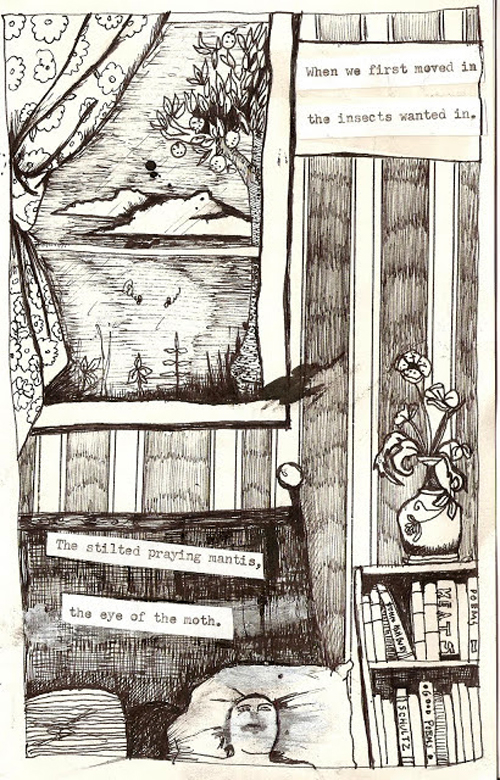

from, THE SECRET INTIMACIES OF INSECTS, 2009 | Bianca Stone

Similar to Farrell and Koch, the comics poetry of Bianca Stone references iconic characters, including Charlie Brown, Lois Lane and Superman. Stone’s collections include Antigonick, a collaborative comics poetry translation of Sophokles’ Antigone created with Anne Carson (2012), I Saw The Devil With His Needlework (2012), I Want To Open The Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant (2012), Someone Else’s Wedding Vows (2010), and comics poems OUR BODIES, OURSELVES (2010) and THE SECRET INTIMACIES OF INSECTS (2009) as well as individual comics poems posted on her ‘Poetry Comics’ website (poetrycomics.com). In an interview I conducted with Stone, she discusses the difficulty of defining her work …

Sometimes I think I’m cheating in calling my work a comic, since they are anything but traditional comics. In many ways I’ve found the pursuit of poetry and comics an overwhelming one, because the two have not been widely joined deliberately. It is not a mere coupling of poetry with the image, rather the image needs to be distinguished from poetry as it pertains to the comic book form…It is a deliberate use of poetry and comics together.4

The simultaneous juxtaposition and synthesis of word and image characterises Stone’s poetry comics, which are otherwise in a league of their own. While visual and verbal segments are more integrated in her recent works and collaborations, Stone explains that her practice evolved by ‘ruthlessly cutting everything…Sometimes a three page poem would end up being three tiny lines. It was so liberating. I then went through all my old artwork that I never used for anything, all the scraps…’ and placed images with poems. As artworks are often created independently of the poem, Stone’s cut and paste process illustrates how non-sequential segmentivity can inform comics poetry and, in-turn, how segmentivity can be critically applied to critique non-linear comics poetry.

The complexity of Stone’s visual-verbal layering is evident in THE SECRET INTIMACIES OF INSECTS. This work originates from a single poem, yet within the comics poetry edition the three stanzas of original text are segmented across eleven pages to create a new poetic rhythm. The first lines are captioned in a cut and paste style, layered on top of a detailed illustration of a bedroom (shown in Figure # IV). A gutter between the first and second panel divides the original stanza and signifies a time shift more significant than the line breaks in the text only version. Rather than translating the original poem directly, Stone rearranged words and describes the comic as ‘slowing down and really concentrating on one poem speaking from certain images.’5 As the poem becomes progressively abstract, she employs more comics devices to increase the disjunction between word and image. Where the protagonist is most present in the text they appear fragmented in the panels, rendered in a picture frame and accompanied by the lines

I secrete sweet coded smells. I mate in any conditions.

The final page of the comic presents three panels, each containing a poetic fragment as the last line is enjambed in separate captions

the vast base of desire ravenous.

Stone’s process and practice demonstrate segmentivity in action, expanding a single word into an entire scene, or an image into a line. These lines, stanzas and images are selected, separated then synthesised, revealing the side of Stone’s ‘work that revels in randomness and fragments, which is, as it turns out, a very powerful thing when assembled in one place’6

This analysis of comics poetry is by no means exhaustive, however, it is hoped that exploration of comics poetry, both creative and critical, expose the potential for segmentivity to inform inclusive modes of analysis. While this survey is capable of capturing only a snapshot of a rapidly expanding field, the cross-section of comics poetry discussed demonstrates some of the ways in which comics forms and poetic devices are being used to broaden visual-verbal possibilities beyond sequential narrative boundaries. The works of other comics poetry creators also warrant continued and concentrated investigations, as the future of comics lies not only in an expansion of comics poetry, but in the application of a model of segmentivity that engages with ongoing experimentation and technologies in contemporary creation and scholarship.

- Clough, Rob. ‘Rhythm & Rhyme: Asthma, The Blot and Comics-As-Poetry’ The Comics Journal. 8 December 2009. ↩

- Farrell in Bennett. Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries. 2012, p.185. ↩

- Farrell in Bennett. Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries. 2012, p.186. ↩

- Stone in Bennett. Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries. 2012, p.170. ↩

- Stone in Bennett. Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries. 2012, p.171. ↩

- Stone in Bennett. Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries. 2012, p.171. ↩