In 1979, Cecilia Vicuña (Chilean poet, activist and artist) tied a red string around a glass of milk and spilled it on the pavement. ‘El Vaso de Leche’ (The Glass of Milk) was simultaneously a ‘precarious’ poem and protest for the 1,920 children who died as a result of drinking milk thinned with white paint in Bogotá.1 The work was silent yet its question echoed; ‘What is possible with poetry?’ More than two decades later, it’s a question poets continue to ask.

With poetic forms and mediums constantly evolving, this discussion focuses on contemporary poetic processes, more specifically recent developments within ‘comics poetry’. My investigation into the emergence of ‘comics poetry’ was fueled by an interest in visual poetics. It began with study of William Blake’s illuminated manuscripts and Stéphane Mallarmé’s ‘Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Aborlira Le Hasard’ (1896), a work often referred to as the precursor of modern visual poetry. By exposing the page and all marks upon it as the matter of poetic meaning, Mallarmé introduced multi-linear reading paths. These spatial and typographical forays were credited with giving rise to Apollinaire’s Calligrammes: Poems of war and peace 1913–1916 (1918) which operate simultaneously as poem and painting. Apollinaire’s experimentation with simultaneity helped spawn concrete poetry movements that spread through Brazil, Europe, Japan and later in other English speaking countries. Mary Ellen Solt’s Concrete Poetry: A world View (1968) charts early developments in this field, including the emergence of the term ‘poesia concreta’ or concrete poetry.2 The term was coined following an exhibition of works by the Brazilian collective ‘Noigandres’ comprising poets, Haroldo de Campos, Augusto de Campos and Decio Pignatari. Their concrete manifesto, first published in 1956, declares …

the concrete poet sees the word in itself – a magnetic field of possibilities – like a dynamic object, a live cell […] the poetic nucleus is no longer placed in evidence by the successive and linear chaining of verses, but by a system of relationships and equilibriums between all parts of the poem.3

Concrete poetry recognises both the spatial and temporal potential of poetry. From Apollinaire’s Calligramme to Joe Brainard’s collaged comics, visual-verbal experimentation has laid the foundations of ‘comics poetry’. In addition to shared visual-verbal structures (typographic experimentation, symbolism, spatial arrangement of stanzas and panels, page layout and rhythm) comics and poetry have an established, though often neglected, history of exchange. Given these mutual visual-verbal foundations, it follows that comics and poetry intersect.

Comics poetry is a field influenced by, though distinct from, concrete poetry, visual poetry and illustrated poetry in its conscious and consistent use of comics devices. While it is true that comics poetry and visual poetry share several formal elements, the use of segmented images, captions, gutters and speech balloons are not consistent or critical in visual poetry as they are in comics poetry. For a work to be classified ‘comics poetry’ it must deliberately employ combinations of both forms and their respective devices. Captions and speech balloons may appear in visual texts like Phillips A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel (1970), but as the title suggests, these occurrences are secondary to the visual ‘treatment’ of the novel.

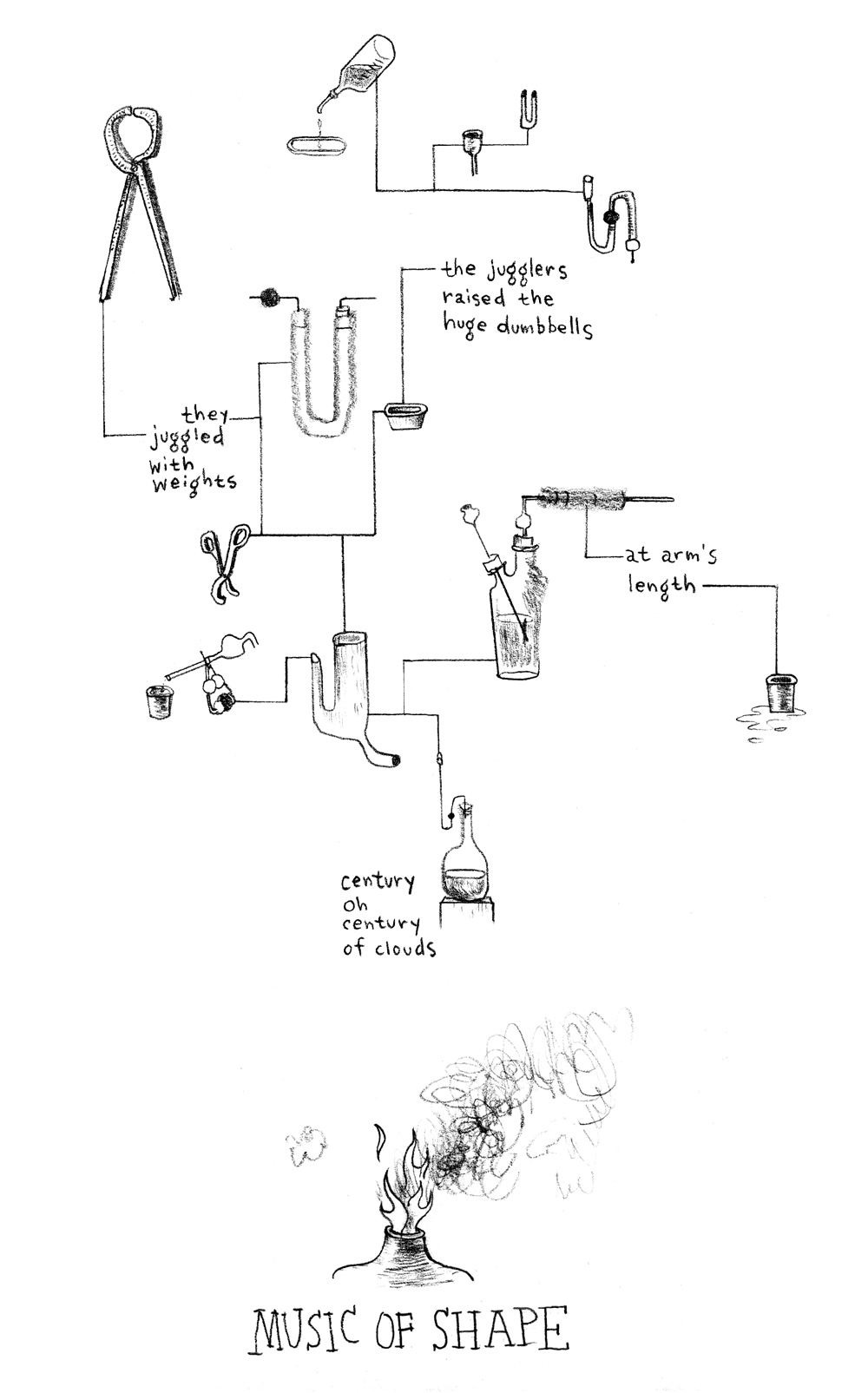

Like Derik Badman, I use the term ‘comics poetry’, as opposed to ‘graphic poetry’4, ‘comics-as-poetry’5, or ‘poetry comics’6, as it refers to the origins of the form rather than the sequential narratives of graphic novels. As Badman explains, ‘Comics poetry isn’t poetry as text with comics images; it’s the whole comic as poetry. The images, the words, the structure, the rhythm, the page, all of it is used together to create the poetry, to create comics in a poetic register’7. As a hybrid form, comics poetry overcomes spatio-temporal divisions and concepts of visual-verbal rivalry to create works that do not strictly operate as ‘sequential art’.8 These works are segmented, often non-linear, non-narrative and experiment with simultaneity, spatial word and image assembly, metaphor, countermeasure, repetition and rhythm as a means of exploring the possibilities of textual-visual language in comics forms within panels, gutters, captions, speech and thought balloons. The term comics poetry can be applied to a growing field of works fall outside of traditional definitions of both comics and poetry. These works include Warren Craghead’s How To Be Everywhere (2007); Matt Madden’s Comic Sestina (2004), Michael Farrell’s BREAK ME OUCH (2006); as well as a host of comics poetry collections by Bianca Stone, Alexander Rothman, Paul K. Tunis, Gary Sullivan, John Hankiewicz, Anders Neilson, Derik Badman, Eroyn Franklin, Franklin Einspruch, Sommer Browning, Kimball Anderson, Kevin Czapiewski, Malcy Duff and Julie Delporte, among others. Before examining a cross-section of these works, it is essential to contextualise the theories underpinning analysis of comics poetry.

Comics scholarship is characterised by the closeness of creators and critics, often one and the same, from Will Eisner to Scott McCloud, Gary Sullivan and Badman. Despite comics experimental and interdisciplinary beginnings, since Eisner defined comics as ‘sequential art’, critics have clung to the narrative confines of the form.9 This narrative hegemony has been perpetuated by McCloud’s definition of comics as ‘juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.’10 Consequently, comics creators and critics have been preoccupied with sequential, linear relationships between image panels and narrative that require audiences to practice ‘closure’ in order to reach understanding.11 McCloud’s notion of narrative ‘closure’ relies on the audiences’ cognition and negotiation of gutters and gaps (the white space between panels akin to line breaks in poetry). According to McCloud, readers fill in gaps between panels, unifying visible and invisible moments to create ‘meaning’.12 Like Dylan Horrocks (2001) and Neil Cohn (2008) I take issue with the narrative limitations and linear assumptions inherent to ‘closure’. In his article ‘Closure’s assumptions’, Cohn contends, ‘(j)ust because we experience reading sequences of images linearly doesn’t mean that is how we understand them.’13 Moreover, the practice of closure is predicated on a narrative premise and direct relations between panels, whereas increasing examples of experimental, abstract and comics poetry are non-narrative and void of traditional sequential panels.

Emphasis on linear narrative sequence in comics has resulted in the neglect of comics poetry by scholars like McCloud, Hatfield, David Kunzle, David Beronä and Douglas Wolk, who continue to preference images in sequence above all other visual-verbal elements of comics. Evidence of limiting narrative assumptions can been found Wolk’s review of Abstract Comics: The Anthology in which he states, ‘anyone who’s used to reading more conventional sorts of comics is likely to reflexively impose narrative on these abstractions, to figure out just what each panel has to do with the next.’14 This kind of narrative imposition blinkers comics analysis, resulting in limiting comparisons of comics to prose and film. For comics creators like Gregory Gallant, (a.k.a Seth), narrative associations have reached breaking point,

Comics are often referred to in reference to film and prose — neither seems that appropriate to me. The poetry connection is more appropriate because of both the condensing of words and the emphasis on rhythm. Film and prose use these methods as well, but not in such a condensed and controlled manner. Comic book artists have for a long time connected themselves to film, but in doing so have reduced their art to being merely a ‘storyboard’ approach.15

Sequential ‘storyboard’ analysis has its place, but narrative colonisation of comics has led to the exclusion of other profitable means for creating and critiquing comics. Beyond linear panel associations and sequential narrative readings, the emergence of experimental, abstract, multi-linear and poetic comics points to the need for alternative modes of analysis that acknowledge the value of spatial arrangement, meter, counter measure, visual trace and deliberate syntactic disjunction to inform ‘meaning’.

While narrative comics undoubtedly account for the majority of the market, a comprehensive mode of analysis must encompass all forms from narrative to non-narrative, multi-linear, abstract, experimental, digital and poetic. Accordingly more formal, medium specific approaches are needed to understand the developments in comics poetry. As Jan Baetens argues in his article ‘Abstraction in Comics’, the ‘a priori approach to narrative in comics as a mere instantiation of narrative in general is now under pressure.’16 Where it was once acceptable to fold the idiosyncrasies of the comics form into narrative analysis, recent developments in abstract comics and comics poetry actively resist narrativisation. Despite this resistance, narrative ‘upgrades’ are continually imposed through sequential modes of analysis.17 Yet as Baetens contends, ‘it is no less possible to gradually “downgrade” the narrative strength of apparently very narrative panels, pages, or sequences by becoming sensitive to the power of abstractive mechanisms.’18 By re-focusing attention on individual segments, rather than narrative sequence, plurality can be achieved. Baetens explains,

narrative and anti-narrative are not so much different forms as different strategies of reading and looking, and that the dominance of narrative norms should not prevent us from seeing the perhaps more covert role of non-narrative aspects. Second, and more importantly, what abstraction finally shows is also the possible frailty of narrative. Even when it is present in apparently hegemonic ways, narrative can always collapse in order to give way to something totally else.19

To recognise the coexistence of narrative and non-narrative segments, especially in abstract comics and comics poetry, narrative impulses must be countered. By remaining open to non-narrative segmentivity, in both poetry and comics, we begin to redress the narrative imbalance.

The concept of ‘segmentivity’20 stems from Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ attempt to distinguish the fundamental components of poetry from narrativity and performativity. Whereas narrativity and performativity depend on the temporal sequencing of events, gestures and images, DuPlessis argues poetry is

the kind of writing that is articulated in sequenced, gapped lines and whose meanings are created by occurring in bounded units, units operating in relation to chosen pause or silence […] Segmentivity—the ability to articulate and make meaning by selecting, deploying, and combing segments— is the underlying characteristic of poetry as a genre.21

Segmentivity apprehends the aesthetic and disjunctive strategies of poetry (gaps, anacoluthon, fragmentation, juxtaposition) through analysis of irreducible segments. Moreover it recognises that the selection and deployment of segments is not dependent on narrative disclosure as it occurs in all forms of poetry regardless of style, culture, structure and musicality. By recognising the plural potential of these components, segmentivity frees poetry, and other literary forms, from the limitations of sequential narrative analysis. Segmentivity therefore provides a framework for a comprehensive theory capable of examining both narrative and non-narrative mechanics and meanings.

In both poetry and comics, visual-verbal segments are not always used for narrative means. Their components are accumulated and arranged with ‘gaps’ that give rise to multi-linear associations and poly-sequential possibilities. Through segmentation, autonomy is regained as visual and verbal mechanisms can be arranged and apprehended in multiple directions more so than the straight lines of prose. As DuPlessis observes, poetry can move beyond limitations of narrative disclosure when ‘organized by leaps, associative logic or juxtaposition, vectors of concerns (rather than mono-directional argument). A vectored text with several directions and gaps is an alternative to sequential narrative.’22 Correspondingly, it can be argued that segmentation, rather than narrative sequence, is the primary characteristic of both poetry and comics. Sequence is a secondary element with narrative disclosure following behind. In contrast to the hegemony of narrative, a model of segmentivity enables visual and verbal segments to be understood as individual components that can be used for non-narrative means depending on creative and cognitive inclinations.

- Vicuña, Cecilia. The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña + QUIPOem. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1997. p.55. ↩

- Solt, Mary Ellen. Concrete Poetry: A World View. UbuWeb Papers. ↩

- de Campos, Augusto. ‘Concrete Poetry: A Manifesto’. UOL online. Originally published 1956. ↩

- Surdiacourt, Steven. ‘Graphic Poetry: An (im)possible form?’ Image (&) Narrative #5. ↩

- Clough, Rob. ‘Rhythm & Rhyme: Asthma, The Blot and Comics-As-Poetry’ The Comics Journal. 8 December 2009. ↩

- Stone, Bianca. ‘Poetry Comics’, 2014. ↩

- Badman, Derik. ‘Comics Poetry, Poetry Comics, Graphic Poems’. The Hooded Utilitarian. 30 August 2012. ↩

- Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art. Princeton: Kitchen Sinks Press, Inc: 1992. ↩

- Eisner, Will. 1992. ↩

- McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial. 1993. p.20. ↩

- McCloud, Scott. 1994. ↩

- McCloud, Scott. 1994. ↩

- Cohn, Neil. ‘Closure’s assumptions.’ The Visual Linguist. 2008. ↩

- Wolk, Douglas. ‘Abstract Comics.’ New York Times Book Review. Holiday Books Edition, December 6, 2009. ↩

- Gallant, Gregory in Ngui, Marc. ‘Poetry, Design and Comics: An interview with SETH’. Carousel, Vol. 19, 2006. pp.17-24. ↩

- Baetens, Jan. ‘Abstraction in Comics’. Substance # 124, Vol.40, no.1, 2011. p. 94. ↩

- Baetens, Jan. ‘Abstraction in Comics’. p.106. ↩

- Baetens, Jan. ‘Abstraction in Comics’. p.106. ↩

- Baetens, Jan. ‘Abstraction in Comics’. p.110. ↩

- DuPlessis, Blau Rachel. Blue studios: Poetry and its cultural work. United States: University of Alabama Press. 2006. p.199. ↩

- DuPlessis, Blue studios: Poetry and its cultural work. p.199. ↩

- DuPlessis, in Bennett, Tamryn. Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries (Thesis). Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2012. p.169. ↩