4

What is the legacy of this disparate group of poet-travellers? What ought we to make of their various refusals and failures to represent Australia in their books? Reflecting on similar questions in his landmark essay ‘Is Art History Any Use to Artists?’ (1985), Ian Burn introduces another faux explorateur:

There is a little-known story about the time Fernand Léger (the French cubist painter) briefly visited Australia in 1956 (…). He was taken for a drive out into the countryside and kept asking the driver to go faster, because, as he put it, ‘the landscape wouldn’t lose its descriptive value’. Léger also remarked about the geometry of the landscape eluding him. Later he was shown several collections of Australian art and some of the pictures provided clues helping create a comprehension. In particular, some 1940s Wimmera landscapes by Sidney Nolan made the translation, exposing a ‘logic in the way of seeing the landscape which worked for Léger’. (4)

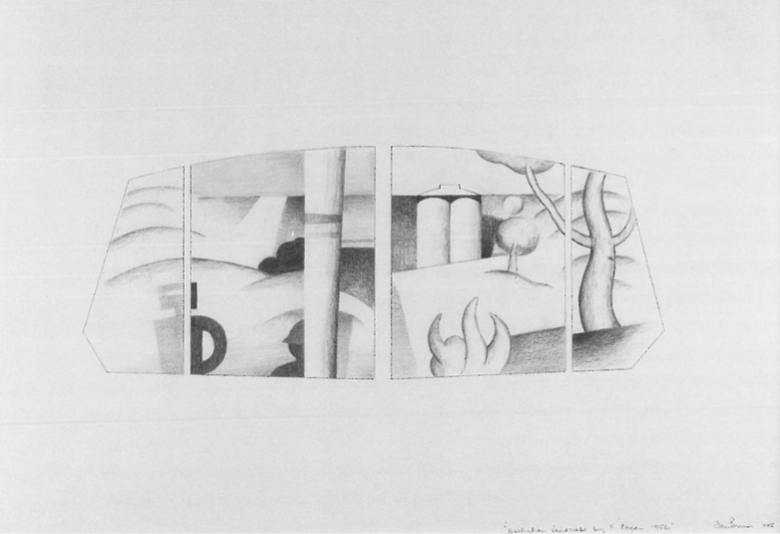

Burn, a significant conceptual artist as well as an art historian, wrote these lines in response to what he saw as narrow jingoism in the reception of Nolan’s art. Yet, unlike the three visitors previously discussed – Roussel, Ashbery and Perec – this ‘little-known story’ is a work of pure fiction. Burn invented Léger’s Australian holiday; it is unlikely that the French artist ever saw, let alone was moved by, a Nolan painting. Facts do not, however, dissuade Burn; the value of an anecdote, he explains, does not reside in evidential proof: ‘An anecdote creates its own necessity, truth notwithstanding’ (3). The power of a story – its ‘proof’ – ‘derives from the fact that it personalises, conveys an intimacy and, as a rationale, is reinforced by the dominant art teaching practices of learning from example’ (3). Grappling with his essay’s titular question – ‘Is Art History Any Use to Artists?’ – Burn is interested in how an academic discipline might support contemporary practitioners. He argues that the personal anecdote offers useful inroads into stultified, intimidating canon. ‘When artists are looking at art,’ he adds, focusing on process over traditional history, ‘they are recognising bits and pieces of their own practice; they are recasting other bits and inventing new uses’ (5). By way of illustrating the radical, anti-institutional approach he is proposing, Burn apes Léger in an intimate pencil drawing, imaging how the artist’s distinctive style might be applied to an Australian setting (Fig 3).

Ian Burn, Australian Landscape by F. Léger, 1956 (1985) black pencil on paper. Private collection.

Burn’s celebration of anecdotes is endorsed by the poet Kris Hemensley, who had emigrated from England to Australia in 1966. Through his conversations with Robert Duncan, during the American poet’s visit to Melbourne in 1976, Hemensley had developed an understanding of literary history as what he calls ‘essential gossip’. ‘You carry your own history with you. (…) And it is this thing of (…) knowing what has been (before you) but feeling that the trajectories of that history are as vivid and active and as energetic if you intersect with them’ (Wright 16). For Hemensley, anecdotes provide footholds on the monumental and shifting face of literary tradition, through a subjective subversion of what Harold Bloom has called the ‘authoritative in our culture’ (1).

Yet as Hemensley and Burn were both aware, what gossip is reckoned ‘essential’ and what is deemed ‘dispensable’ is frequently a product of geography: an anecdote told about Paris has more cultural purchase than a story set in Parramatta. In Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (2000), Dipesh Chakrabarty has termed this phenomenon an ‘asymmetry of ignorance’, wherein cultural metropoles dominate the pre-conditions of literary historical knowledge: Melbournians can be expected to intimately understand the New York School in all its relational nuance, but their New York counterparts may selectively sample from Australian writing broadly, if at all (27). Burn was alert to the implications of this cultural logic, in no small part due to his time living in London and New York, and his Léger fantasy inverts predictable dynamics of influence: the French master is turned protégé, praising Nolan for ‘exposing a logic in the way of seeing the landscape.’ In his pencil drawing, Burn situates Léger looking through the windows of a Triumph Mayflower, in an undeniable homage to The Car (1955), John Brack’s oil painting of a family on a weekend drive. In Burn’s reversal, Australian art quite literally frames Léger’s view, providing him the window through which he sees the world.

Overcoming provincialism in history, Burn suggests, requires not only new forms of scholarship but also new modes of aesthetic appreciation. Near the end of his essay, he provides the biographical basis for his Léger fantasy: ‘I recently stood in a room full of paintings by Léger thinking about how “Australian” they looked,’ he writes. ‘He was one of the most important routes into European modernism for a few Australian artists – for me, he suggested ways back out’ (14). ‘I am interested in “Australian” activities insofar as they relate to the world (and total) reality,’ Hemensley wrote in 1977, in a similarly introspective mode: ‘it’s a somewhat ambivalent situation I occupy’ (232). For Hemensley, the importance of international visitors to Australia is that ‘they break the isolation and isolationism of Australian poetry,’ which, he added, ‘is a goal still to be achieved’ (228). ‘(O)ur major task is to account for the “Australianness” of bits of Léger’, Burn concludes: ‘it is not, as some have argued, the process of “Australianising” cubism, expressionism or whatever’ (14). In Burn’s resolutely antipodean inversion, the question is not whether a visiting author ‘took anything (from Australia) for (their) books’, but instead whether we, as Australian readers, can find the local in their foreign art.