A Whistled Bit of Bop by Ken Bolton

A Whistled Bit of Bop by Ken Bolton

Vagabond Press, 2010

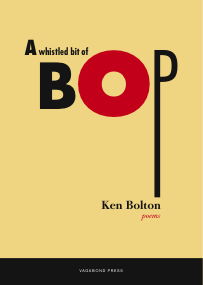

The cover of A Whistled Bit of Bop makes use of a cool, spare design, reminiscent of 60s jazz album covers. It’s a change from the handmade look of many of Bolton’s earlier collections. The O and P of ‘BOP’ are also the record and arm of a turntable; the circular author photograph on the back cover – showing Bolton in a thumb-to-chin thinking pose – might then be the sticker in the centre of the disc about to be played. The collection contains twelve poems, nine of them long or longish ones. There are poems here which begin by describing the scene or occasion of writing and find their way from there, collaging thoughts, questions, quotations, references to R & B and jazz musicians, and imagined meetings with others (poets living and dead, a talking pigeon).

The first poem, ‘Double Trouble’, as well as being about waiting to go and have a haircut, is also to do with the way that the various times of the poem bear on each other. It begins impersonally, with two quotes – or epigraphs brought into the body of the poem – by a perhaps unlikely pair of poets, Paul Verlaine and Bill Manhire. This is one way Bolton’s poems often begin in this book, by setting up a kind of antiphony or call and response and letting it play out. The poems can be, in this way, dilatory, but often, too, a thought will arrive and leave just as quickly. Bolton’s style can make the process of writing the poem seem effortless; however this particular poem was originally published in Otis Rush in the 90s, suggesting that he might have been tinkering with it for years.

There are plenty of beautiful and sharp, critical and concise observations throughout the book. The second poem, ‘Europe’, the longest at 23 pages, records a perfect image of London: “A helicopter beating at the sky overhead / returns, like a wasp at a pane of glass”. Another good description, from the previous page in the same poem:

cloud, like

Immobilized white steam— soft, large, silver-lined —

against the blue

the usual repertoire

A fragment from ‘Hits and Misses’, a letter-poem to Sal Brereton as well as a short history of contemporary Australian art, could be one of Laurie Duggan’s miniatures:

Australian Painting

circa 1970

a fat guy spattered

with paint

In the same poem, Bolton writes:

Offering me my drawing

of ‘Strange Cove’

backis morbid

but we all are

I mean: we’re all going to die“all morbid”, in that sense

(“moribund”).I’d love it!

(The picture- not death!)

Bolton has said that his poetry is largely about “pacing, emphasis, weighting”, ideas that are exemplified in this poem. I love the slight and then sudden changes as the feeling of “morbidity” (not “melancholy” as I first thought) provoked by the offer of a picture back from an old girlfriend shifts, hesitantly, into the stronger, more final, “moribund”, which times itself out over four or five blank lines to makes way for a more practical response (“I’d love it!”). A few lines down, of a photocopy he has of the drawing in question, Bolton says that he doesn’t look at it too often: “I like to keep its / ‘charge’’’.

In ‘Late Night Reading’, a poem in four sections, each section is about or addressed to four admired poets – John Ashbery, Peter Schjeldahl, FT Prince, and Ted Berrigan. The poems that are addressed to other poets and friends are some of Bolton’s warmest – see for example his poems for John Forbes in At the Flash and At the Baci. The first section of ‘Late Night Reading’ concerns Ashbery and speculates on meeting him. Prompted by staying up late reading Ashbery’s first book, the self-consciousness of imagining such a meeting intersects with its telling: “In fact, he has spoken / I haven’t heard – / lost in the amusing / disjunctions / of this scenario”. The description of the fan’s nerves are good too:

“I didn’t catch your name.”

It’s a question,

but he says it

in the flat, polite,

American way.

“Oh!” (I have

forgotten myself.)

This also gets the calm and unemphatic tone of Ashbery’s speaking voice. The meeting doesn’t feel forged. It seems to be an agreeable and plausible thing to happen, or to have happen – though imagined – rather than something longed for or regretted. In this collection Bolton often returns to the speculative mode, and this gives him greater freedom from the strictures of tense.

The last of the four tribute poems is a riff on Bolton’s own suggestion to his friends that they visit Ted Berrigan’s grave. It starts off with the excitement of a wild plan that becomes more reflective as the memories of other deaths – of friends and admired poets – come in. America’s distance from Australia relative to the influence of its poets is a topic explored by Louis Cabri in a recent article in Jacket. Cabri argues that Bolton’s poems are fascinated by this distance; that while they are filled with references to American poets and pop culture, they are importantly written from Australia: “‘America’ comes to him.”

But the references aren’t only American; from ‘Double Trouble’, for example:

Later, I sing

“Downhearted” for a moment.

the Australian Crawl songWhy were they

so intellectually unrespectable?

It’s a great question, sort of an Australian koan – and partly, too, because it gestures towards a neglected conversation between poetry and cultural studies in Australia. ‘Mary’s Blues’ (with the wonderful, unattributed epigraph, “soft as one’s character, melancholy as one’s attractiveness”) is a four page poem whose occasion is flicking through Frank O’Hara’s poems while listening to a record, the description of which seems to nail something about Bolton’s writing:

Pepper Adams

Is working in

a busy decisive way

The third line brings together busy-ness and decisiveness into a single quality. It suggests that the changes that take place in the midst of an improvised jazz piece are always decisions, not random. It is suggestive too of the level of attention and the range evident in Bolton’s poems, as well as their thinking at each phrase and turn of thought. Again, in the same poem ‘Mary’s Blues’, the qualities of intense spots of concentration within the greater bustle of the tune is what is picked up on in the music playing:

it is somehow

bustling

& ‘lyrically sensitive’

at the same time

& concentrated

One tends to treats the abundant references in the book as condensed operators, potential links to different atmospheres and or times (Pepper Adams, Jimmy Liggins, Archie Shepp). But they also inhere in the world of the poem and the life it describes, and in this way they are working parts of the poem’s thought-process as much they are simple shout-outs. The last lines to ‘Mary’s Blues’ make a list of these names of friends and influences, which Bolton describes as:

fixed points

whom I sail ‘by’,

‘beneath’, ‘between’

Mary,

Mill, Craig,

Coltrane and Pepper Adams –

or Cecil Payne, if it was him –

Frank O’Hara

The poems are less exuberant than Bolton’s – classic? – 70s and early 80s books like Four Poems, Blonde & French, and Christ’s Entry into Brussels or Ode to the Three Stooges. It seems to me that in contemporary Australian poetry Bolton has much in common with poets whose mode is discursive and often problem-solving, Jennifer Maiden would be one. Bolton’s poetry might be less politically and ethically searching – and certainly their interests differ – but their poems share an open, discursive way of letting the poem work itself out rather than letting the lines stack into place. All of the various parts of language, including punctuation, appear as the working out (as in a maths problem) rather than the retrospectively organised details towards an answer, and this goes hand in hand with stretching out the dimensions of the poem, and allowing in more peripheral questions and spots of attention to appear. There’s a democratic order at work in Bolton’s poems: the ideas, images and questions that keep the poem moving are given as much right to exist as the image that might set you mentally reeling. Robert Cook describes this well (writing about Bolton’s art criticism) in an introduction to a recent interview he conducted with Ken Bolton: “I do not get the sense that once he’s found where he’s wanting to go with a piece that he starts again and sets up the flagposts, makes it all coherent as a whole … I get the sense that he leaves it alone because the steps are essential to convey the activity of finding an idea.”