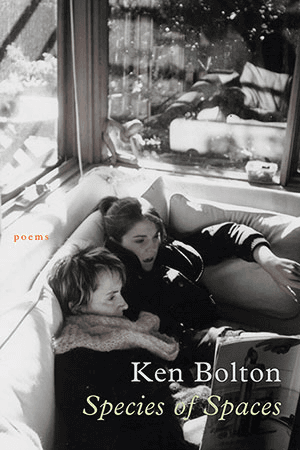

Species of Spaces by Ken Bolton

Shearsman Books, 2018

Ken Bolton’s thinking is never too relaxed, but moves restlessly and anxiously, across people, cultural references and disparate locations even as he writes, or so it appears. And the resultant poems also seem to be unfiltered by any desire on the poet’s part to be ‘poetic’. But perhaps this is illusory. The poems are, after all, carefully considered and crafted, occupying the page determinedly even though the poet writes as if the events and thoughts he references are taking place in an ongoing, urgent present, via a stream of consciousness, and that the last thing on his mind is making ‘poetry’. Indeed, Bolton records something that looks like immediate, unfiltered thought and his compelling purpose is to register rather than editorialise.

The poems are laconic, sometimes funny and disarmingly casual in their address, coupled with seeming randomness in both diction and punctuation. He appears to avoid any striving towards the considered, drafted poem and instead follows impulsive thought as an end in itself. We are provided then with access to the joys, anxieties and emotional complications present in a life recorded in real time and space. However, we would be wrong to consider the work to be confessional in any sense, nor is it ever reliable autobiography as such. Bolton is not interested in either but rather in wider philosophical questions about the nature of perception and what impact cognition has on emotion and happiness. Further, the poet himself is the investigated subject and the focus of an ongoing, self-scrutinising, scientific experiment in poetry that is essentially about thought.

The first poem in the book opens with an account of an ‘Ongoing Moment’, and demonstrates Bolton’s capacity to register his own shifting thoughts via a disparate narrative that has the poet and his partner, the author, Cath Kennealy, at an airport where they are soon to ‘fly out / a few hours late’ on some trip or other. The situation is described as ‘– anxiously perilous –’ but it is also charged with possibility and as a consequence the poet feels:

less pissed off than normally & separated – because we booked our flights separately. I don't know where Cath is sitting or what she's doing – well, reading probably ... (‘In Three Parts: A Report on the Ongoing Moment.’ 9)

This is remarkably ordinary and prosaic, even dismissive. However, it is also extraordinary in its insistence on the recording of the banal vicissitudes of a lived moment. And there is a febrile urgency here that is compelling in a poem that provides an eye onto the realm of the poet’s ‘live’ thinking and writing (as illusory as that might be) and these are inseparable. Here, the ‘place’ in the poem, in this case the airport, becomes an anchor of sorts. This is critical, not because the poet is bent on ‘location’ for its own sake or because he want to ‘document’ as such, but because each space or person mentioned (or indeed any wider cultural reference that pops into his head) is ultimately and sadly fugitive. There is a deep apprehension of inevitable and painful loss even within the lived ‘present’. The mind traveling as it does, erratically, uncontrolled, with ‘a mind of its own’ as it were, inhabits a deeply anxious space (one of the ‘species’ of spaces in the book’s title) where in any poem, the wider world can and does intrude: Miles Davis might wander through, or Stendahl, Cath (Kennealy), Pam (Brown), or indeed any of the poet’s friends and fellow poets, past and present as well as abstracted, wider philosophical concerns, or whatever. And while these thoughts might well be triggered by a particular place, in this case an airport (there is also in this and other poems: ‘Leigh Street’, ‘on the train back to Sydney’, ‘Gilbert Place’, ‘Melbourne’, the ‘South Coast’ and so on, names that are all familiar enough), the poet remains alienated. ‘Place’ becomes ‘no-place’ and in Bolton’s mind anyway, out of time.

For this reason, the airport, along with the delayed flight experienced in ‘A Report on the Ongoing Moment’ provide the perfect metaphor to represent the poet’s dislocation from his own life and that of his friends, because forced to exist in a no-place, the airport, even temporarily, the poet finds himself unattached, a notion that is both exhilarating (because it allows space for the mind to wander associatively) and anxiety provoking (because Bolton is subject to the vagaries of forces beyond his control). It is this that becomes the subject of the poem as he riffs about: meeting friends, working with a friend on a catalogue, describing book launches that made everybody ‘too nervous to relate much’ and thinking about poets like John Tranter who goes off for a drink ‘while the computer composes poems for him …’ and Pam Brown whose work: changed then, too / & continued to change, /And then there’s mine / – my abiding problem. / When does this plane land? This is marvellous in its accumulation of apparently disassociated thought so exhilaratingly and urgently expressed.

While on one hand this poem and more in Species of Spaces, celebrates the mind’s wanderings as a kind of freedom, there remains a palpable anxiety and underlying sadness to do with the notion of impermanence that haunts many poems otherwise witty, even rakish and certainly perverse. And as Bolton reminds us, the world moves and everything that we know (and love) shifts too. So, by implication, despite an apparent surface banality and ease in the poems, time and death remain ever present for Bolton, investigated in poetry that concentrates on the spaces occupied by a shifting, lonely mind at work: ‘Too many /… of the people I know about, / care about / are dying / a / feeling / more than a thought’ (‘Spot Check’ 61)

Bolton travels as the ‘hero’ in his own poems, wandering like a flaneur, with apparent casualness. And if he needs to be funny at times, that is belied by the utter seriousness of the ultimate mission, an attempt to understand or at the very least register the unalterable motion of ‘thought’, as mercurial as that is: A guy, / unintentionally debonair, / using a long, furled, / pink umbrella / like a walking stick / flamboyant / but not consciously so, / lost in thought. / As who isn’t? –Thought’ / Each with / our own. (‘Gilbert Place–Cafe Boulevard’ 78)

Evidenced here in this ‘quest’ towards understanding (that’s what it is, as old fashioned as that may sound) there is a lyric heart at the core of the seemingly random, even sometimes chaotic life lived, or anyway surveyed in the poems. Further, there is a yearning for ‘fixedness’, predictability and contentment.

Act as if the world exists, the Surrealists said. It, certainly, won't act as if you did & me, I'm barely here. Tho happy at this moment. (‘Two Melbourne Poems, June 2012’ 95)

‘at this moment’ suggests that there may well be other moments, perhaps many moments, or even ‘usually’, when the poet finds happiness more elusive.

Bolton’s testing, roaming lines attempt to address, even within their shape and arrangement, the impossibility of pinning the sometimes banal mind-scape he inhabits, where accidental meetings in thought are always possible, where love is given and taken, where poems begin and end, where people are described as going to events or not, where friendships always matter and from where the mind is free to wander albeit through uncertain terrain. Thought itself wanders, sometimes anxiously, from place to place, person to person, idea to idea. And this is what Bolton captures best, in verse that is itself a vivid representation of the very mind shifts that go on relentlessly and for most of us, unconsciously.

...with Kurt, whom I've never been closer to, & Dennis & Laurie (whom I finally got to relax with– (‘In Three Parts: A Report on the Ongoing Moment’ 9)

That Bolton replicates a mind shifting through mental and physical ‘spaces’ of various kinds in his poetry is his particular achievement. In this, he proclaims the extraordinariness of the ordinary, with the proviso that we must understand an essential paradox: that is, to travel (in thought or bodily) is only possible if there is also a notion of fixedness and stasis. The poet to be free (and this seems to be what the poet desires) must first locate a space to travel from, to move away from. The obsessive quest to locate a place that the mind occupies in stillness and quiet is ultimately doomed. This dilemma is at the heart of the poet’s fundamental anxiety. Bolton’s poems are like the notes pinned to the door when you go out. Are you telling others where you are, or yourself?