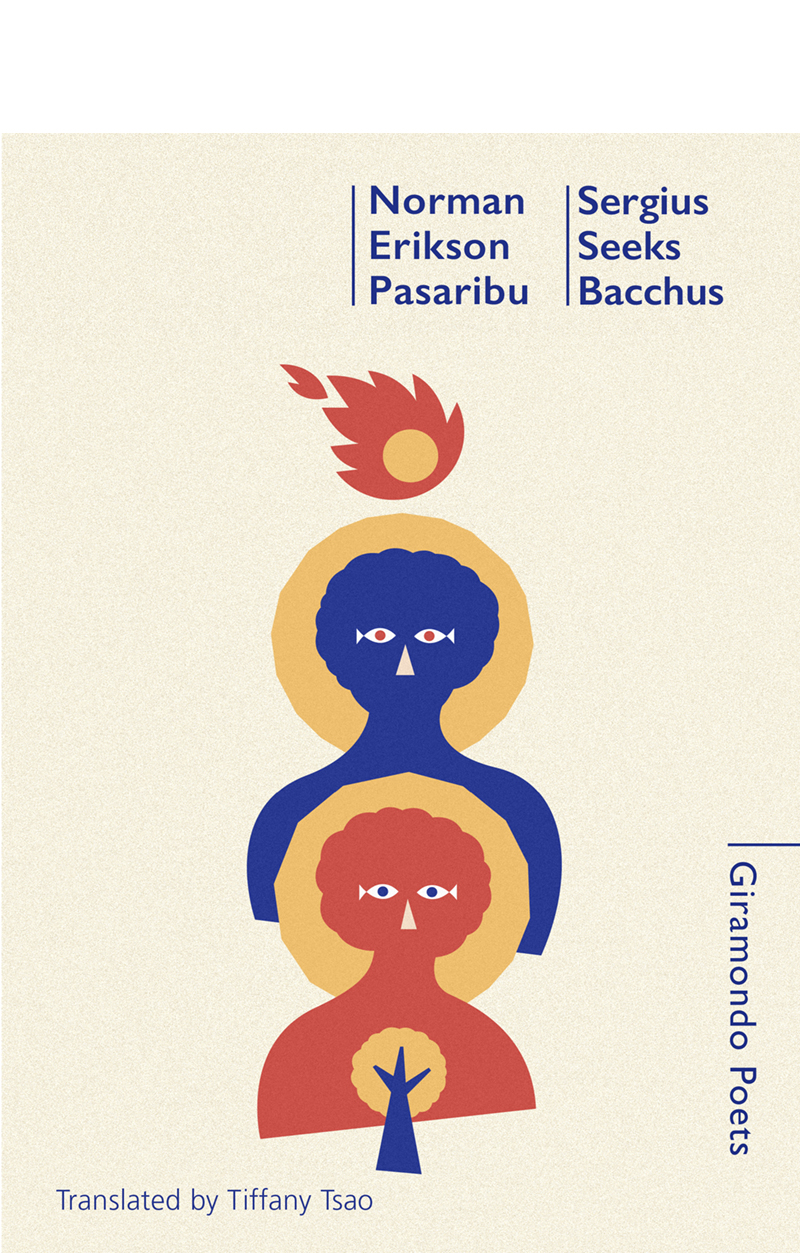

Sergius Seeks Bacchus by Norman Erikson Pasaribu

Translated by Tiffany Tsao

Giramondo Publishing, 2019

Sergius and Bacchus were fourth century soldiers in the Roman imperial army and also devout Christians and lovers. They kept their religion and sexuality secret but once their Christianity was discovered they were to suffer terrible torture and eventual death as martyrs, hence their sainthood into the Christian Eastern Orthodox Church (centred at that time in Byzantium). Bacchus’s and Sergius’s sexualities remain contentious, particularly within the Church and at least as far as some church historians are concerned. However, as travel writer Will Harris points out, ‘parallels between their secrecy and that of so many queer communities across the globe has turned them into something of a symbol for queer visibility.’

This ‘visibility’ remains especially potent, indeed emblematic, for the Indonesian author Norman Erikson Pasaribu. ‘Sergius Seeks Bacchus’, his first book, is located firmly within an apprehension of sexual oppression. Many queer Indonesians (of whom Pasaribu is one) endure persecution or, at the very least, the fear of it at the hands of an increasingly fundamentalist, non-tolerant society, particularly in some regional areas across this huge island group. While homosexual acts between consenting adults are not illegal across the archipelago, there exists widespread harassment, prejudice and shaming especially in Aceh and West Java where the strict observance of Sharia law is more pronounced. Also, in other parts of Indonesia, where Sharia law is not practiced, there exists an implicit tension within society in relation to matters of sexual identification and gender mobility. And while much of the country moves inevitably towards more democratic, secular values, there is an opposite push to shift society in the direction of more conservative, Muslim orthodoxy. It is indeed a paradox worth noting that while democratic impulses remain strong, as millions of Indonesians continue to explore and experience western-style electoral democracy, prejudice towards homosexuality is also marked, as significant numbers move to defend what they see as threatened religious orthodoxy. My own partner’s family is representative of this development in thinking and observance. Nieces, aunts, cousins and sisters are more than ever drawn to wearing the hijab, as a sign of their own virtue and religiosity. That they feel this is necessary, particularly where the prospect of marriage is concerned, was certainly not the case even ten years ago. Their male counterparts are also drawn to stricter and more public observance. The increasing numbers of those attending religious service is evidence of a move towards conservatism in Jakarta – hitherto the centre of a more relaxed attitude towards Islam and its teachings.

Being both gay and Christian, Pasaribu faces difficulty on two distinct fronts within his own country. His response is a creative and rebellious one. In Sergius Seeks Bacchus, a book that appears to be mostly ‘biographical’, even ‘confessional’, he explores the confusion and complexity of his own identity, while expressing deeply felt individual protest and determined self-belief – a belief honed, as it appears, within very personal family difficulty, religious questioning and more broadly, social alienation.

In ‘Erratum’, the opening poem, he asks:

What was he thinking here, picking this body and this family [?]

Pasaribu expresses a gay lament, via a second person narrative, that is unfortunately all too familiar to many individuals in Indonesia and elsewhere. In Indonesia especially, the experience of familial alienation is one that millions suffer, leading to the kinds of domestic scenarios as described in ‘Erratum’. In this poem Pasaribu writes within a kind of casual and conversational address that invites the reader to share intimate feelings including the stress of conflict. The very casualness of address is distinctive in the poems generally and encourages an immediate identification, if also at times representing an expressive awkwardness as the author attempts to marry poetry with narrative urgency or political statement.

In ‘Erratum’, we can certainly feel Pasaribu’s sense of dislocation when describing what happened:

not long after his first book came out, [when] as his family sat cross-legged together and ate, he told them it wouldn't end with any girl [...] and here as he stood by the side of the road that night, all alone, cars passing him, his father's words hounding him, Don't ever come back, Banci, and he wept under a streetlight ...

While this particular scene, or a version of it, is enacted over many households across the Indonesian archipelago, it appears here to be a painful and immediate memory for Pasaribu himself as he continues to negotiate the thickets of family rejection and intolerance, while attempting to live a creative life in the capital far removed from his family. That the poet asserts ‘biographical fact’ is of course an assumption on my part. However, the intensity and consistency of information provided across the poems would seem to support this view. While Pasaribu provides a ‘speaker’, my suspicion is that the speaker is a mask for the poet himself and that the resultant work is to a large degree ‘confessional’. The ‘mask’ also provides at least a little protection from potential difficulty, legal and social.