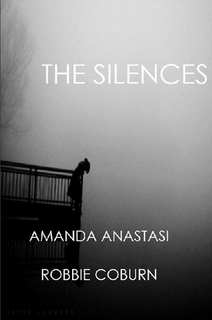

The Silences by Amanda Anastasi and Robbie Coburn

Eaglemont Press, 2016

These 41 pages from a revived Eaglemont Press (once run by the late, revered Melbourne poet, Shelton Lea) contain the first collections (or first half-collections) of Lea’s much younger fellow-Melbournians, Amanda Anastasi and Robbie Coburn. It’s analogous to two good friends buying a very small inner-city flat to get a toe-hold in the daunting real estate market of that city. Bigger things are sure to come later.

The book’s concern with various sorts of silence (and perhaps the reasons for them) starts from its first poem, ‘The Initiation’. It’s by Anastasi and details the treatment of a somewhat reluctant infant being christened, probably in a Catholic church, given ‘a constant male rhythmic murmur’ of the priests. The baby sets up ‘a persistent ostinato cry’. In reply, it receives ‘a protective stroke of the head’ before the poem ends with ‘and the hushing. / The endless hushing’. We’re not told which sex the baby is but one suspects she’s female.

The use of such implication and indirection is typical of Anastasi’s work more generally and yet she and Coburn stop well short of the densely-packed lexical obscurity that currently prevails in some of Melbourne’s poetry circles. Something of the future of the baby just referred to may be sensed in Anastasi’s later poem, ‘Wing’, where the flight of a bird demands that ‘the only posture is that of crucifixion’. The last four lines, however, are notably optimistic: ‘The open-mouthed dependency / of the bristling nest is far behind. // There are many destinations. / The sky is the resting place.’

A comparable sense of opening out occurs in Anastasi’s ‘Night Arrows’. First, the prevailing background of the book is re-established with: “A dog yelps / at the alteration in the wind. // The empty night is an ear, / collecting all that is dismissed.’ Finally, the speaker decides to ‘embrace the unknown, / not the frightening known.’

Robbie Coburn’s poems are somewhat different to Anastasi’s, despite a number of shared assumptions and techniques. This is felt particularly in those poems stemming from Coburn’s farming background. Like some other poets of similar origins (the late Philip Hodgins, for instance, or Brendan Ryan) Coburn’s rear-vision portraits are far from romantic. As he says in ‘Suicide Country’: ‘living in the country remains with you long after you’ve gone / becoming a second skin dislodged when away from the grasses …’

This ambivalence continues in other poems such as ‘How I Feel About Being Here’ which concludes: ‘I love all the things I hate about being here.’ The majority of Coburn’s poems are, however, like Anastasi’s, set in the city – Melbourne, we may assume. Most of them have a somewhat romantic, young man’s angst. ‘Night Walk’, for instance, ends with: ‘from where I am standing / the damage is immeasurable / / no one on the road at 4am / listening / to the cars approaching’. Later, a poem called ‘Missing’, in its opening lines, seems almost to continue the earlier one: ‘dawn comes not unlike / the sleeplessness preceding it, / unalterable and dragging through your breath.’

Sometimes, Coburn moves a beyond his youthful urban despair to produce slightly longer, more fully-achieved poems that go deeper into the causes of the malaise – and, even better, imply a way out of it. A fine example is ‘Lines to Myself’. It’s a persuasive evocation of a kind of undiagnosed and unnamed mental illness. Half way through, the poet says: ‘you must understand that your mind is not your own. / the emergence of fear settling into your breath / is not a fault of character, not weakness, / and this imbalance is beyond your control’. This could also be a helpful psychiatrist talking but at by end of the poem the narrator realises: ‘I can promise you something … / one day …. / you will recognise something new about / the image distorting in the wet glass. / I tell you now, // you won’t always be so unwell.’ At a time when young male rural suicides are a major problem in Australia, ‘Lines to Myself’ offers a sharp and useful insight.

It’s important to insist that The Silences is no mere arrangement of convenience. Indeed it’s something of a livre compose, despite its having been written by two separate poets. While Anastasi and Coburn do have their differences, the reader may surmise that, if their names were taken off the poems, The Silences would still read like a coherent, well-organised first collection. The title itself suggests a certain bleakness and the imperfections of human communication which are reflected in many of the poems. This is no chatty celebration of Melbourne’s coffee culture. It’s more an inside-on-a-winter’s-night-back-to-work-on-Monday sort of feeling. It will be interesting to see where these two young poets go next.