The Herring Lass by Michelle Cahill

Arc Publications, 2016

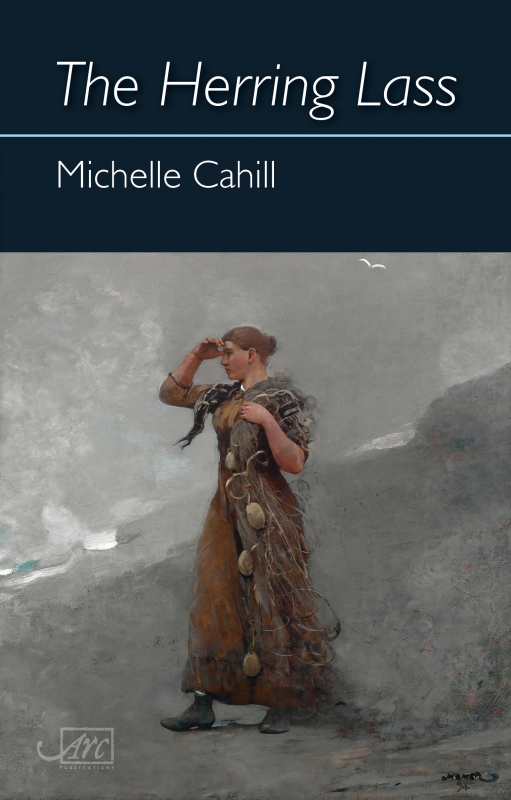

Michelle Cahill is well-known to contemporary Australian readers as a poet, editor and fiction writer. She is the winner of the 2017 UTS Glenda Adams Award for New Writing (one of the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards), the Val Vallis Award, and the Hilary Mantel International Short Story Prize, and has been shortlisted for other major prizes. The Herring Lass is Cahill’s fourth collection of poetry, and her first with a UK-based publisher. The transition from an Australian publisher (Cahill’s third, Vishvarupa, was published by Five Islands Press) to a British publisher (Arc) should bring Cahill’s work to greater prominence within the global Anglophone reading community. The front cover of The Herring Lass reproduces Winslow Homer’s The Fisher Girl (1894), introducing the themes of female strength, endurance and watchfulness, and creating unity with the collection’s title and title-poem. The back cover features praise quotes from Sarah Holland-Batt and John Kinsella, emphasising Cahill’s status as one of Australia’s leading poets. Indeed, Cahill is widely published and anthologised.

The poems in The Herring Lass are preceded by a quotation from a poem by Robin Robertson, which reads: ‘I hold you fast, until you are flesh again, / seal-herder, seer, sea-guardian: / you who can only tell the truth, / show me how to find a fresh wind / and a safe harbour’. The epigraph introduces some of the major tropes of the collection: the sea, transformation, truth-telling, discovery, safety and home. Cahill was born in Kenya; she has Goan Indian ancestry, has lived in the UK and Australia, and travelled widely. Unsurprisingly, her poetry is transnational and addresses issues such as diaspora, boundary crossings, belonging, and loss; the book is dedicated to fellow poet Lyn Hatherly, who passed away in 2016.

The Herring Lass contains fifty-three poems, of which just six are longer than thirty lines. Thirty of the poems have twenty lines or less; Cahill clearly favours condensed lyric poems. Eight of the fifty-three poems experiment with structure; however, Cahill usually employs traditional structures and forms, including a sonnet sequence, and often uses tercets and quatrains. Cahill does not use rhyme-schemes, and deploys rhyme subtly and sparingly. The poems often contain traditional poetic techniques, especially similes, alliteration, metaphors and enjambment. Cahill creates a variety of speakers and often inhabits the voices of others; the first person voice is used carefully and infrequently. The poems utilise an impressive range of locations on four continents: Australia, Africa, Asia and Europe. A number of elements and themes appear repeatedly, including aspects of nature like trees, wind, oceans and rivers. The poems feature a variety of birds and animals, including a thylacine, dingo, bear, and wallaby. Pervasive themes include grief, loss, power, distance, home, language, identity, migrants and refugees. The thematic and geographical range of The Herring Lass is impressive and inspiring.

The poem ‘Her Dream’ is an excellent example of Cahill’s ability to inhabit the voices of others; it is written from the perspective of Sarah Milligan, who was the housekeeper for David Scott Mitchell, the founder of the Mitchell Library. The speaker declares:

In the dream, I become an illiterate moth or a wingless louse, pulverizing monographs to velvet dust, chewing the starch that fixes leaf by leaf to the bondage of light.

Here Cahill ventriloquises the voice of a woman from another time, who in turn dreams of taking on a non-human identity. Such irony, complexity and dexterity is typical of Cahill’s work.

In ‘Twofold Bay, 1930’, which describes the capture of a whale, Cahill includes both settler/invader and Indigenous history in a precise, visceral and sympathetic narrative. The speaker declares ‘museums are white man’s allegory but dreams of killer / and Koori whalers rewrite the past in undercurrents’, and a few lines later, ‘… I can taste the words whiten / into thin milk of settler culture, bloodlines turnstiled’. Thus Cahill combines history, culture, storytelling, hunting and nature, demonstrating her ability to powerfully blend the local and the global, the specific and the universal, the constructed and the natural. Cahill’s capacity for creating dense, specific and concise poems, while simultaneously addressing issues that transcend time and space, and thus attain universal relevance, is most impressive here.

Cahill’s adeptness at inhabiting other voices is demonstrated in the last stanza of ‘Pirogue’ when the speaker proclaims:

… I am one of Senghor’s thin-legged, migrant sons, too proud to beg for breadfruit; hungry for Spain. Listen, today we threw a decomposing body overboard – and prayed.

The African migrant speaker insists on being heard, and thus the poet likewise demands that her readers pay attention and refuse to ignore the horrific realities of migrant and refugee experiences.

The Herring Lass also contains poems focusing on the personal and questions of belonging and memory, often using metaphors, similes and experiences drawn from travel. In ‘Hemisphere’, the speaker admits, ‘I might question my life in quatrains, the past ferries me back / to home in another hemisphere, to asphyxiating bushfires’. And, in ‘Postcard from Childhood’, Cahill reminds her readers that ‘Nothing shelters us from memory, its tender waves, / nocturnal voices like postcards from childhood’. Likewise, in ‘Mumbai by Night’, the speaker claims ‘… Time is a fixed currency without counterfeit, / so brief it leaves me cheating myself with words’. Close attention to the relationship between language, thought and communication also threads its way through these poems.

While this is an impressive collection, certainly one of the best produced by an Australian poet in recent years, it is not quite flawless. On a number of occasions, Cahill ends lines with weak words, particularly prepositions and articles. Placing specific nouns, verbs or adjectives at the end of such lines would have created stronger line breaks and more impact; however, this is a minor quibble and probably reveals more about my poetics than it does about Cahill’s poetry. The Herring Lass provides abundant evidence that Cahill is one of Australia’s leading contemporary poets; moreover, Cahill must now rank in the top-tier of Anglophone poets worldwide, and her reputation should continue to rise.