Cities by Petra White

Cities by Petra White

Vagabond Press, 2021

Petra White’s poetry has been highly and widely praised, celebrated for its seriousness, its engagement with poets like Petrarch, Dante, Coleridge and Donne, its ability to ‘recall’ these famous European names and their famous poems. She is presented as a serious poet, and has managed to get her ‘kind of Collected-poems-so-far’ (Duwell) onto the VCE Literature text list. I wonder what this says about poetry in Australia. Her poems are so good on one metric (studious, ‘clever’, instructive), and so bad, downright naughty, on another (stylistic and/or political ‘radicalness’).

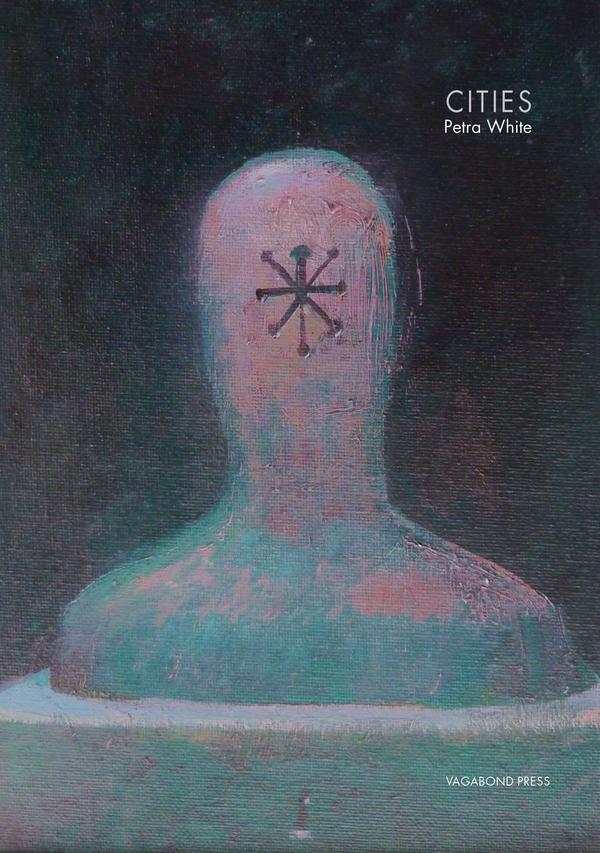

Even before you open it, Cities has an aura. The cover has barely any textual support, an identical Anthropomorphic Deity (Julian Gordon Mitchell, oil on canvas, 2015) looms over the front and back and no blurb. Despite this openness, there is enough paratextual material to push us toward a particular reading. From the Vagabond website: ‘Cities makes playful and lyrical incursions into myth to explore the nature of grief for a mother while becoming a mother, and the difficulties of love … [And] “journal” poems [partially about the] strangeness of prolonged lockdowns’ for life in global cities. Quite a heavy load.

White’s poems are sombre little lights in darkness. I read them closely, slower than I normally would. I’m even compelled to speak the words aloud, a little treat. They feel old and demanding. (What are they demanding?) It is nice to slow down, something I’m not very good at, especially nowadays. Poetry ‘helps’. I’m wary of the therapeutic in art, but White’s decision to publish Cities suggests her belief in poetry’s usefulness for a troubled soul. The poet brings wisdom through elegy and eulogy in the first two of four sections:

The lights of the living are not lost on the bygone, they drink them up like baby birds with sinewy necks. Drink the light that swims through Hades, and are warm. Oh my dead, I will be your queen.

But White is cagey in her extension of the self in mourning. To study her grief, she turns to the mythic figures of Demeter and Demeter’s daughter, Persephone, queen of the underworld. These two deities form a transcendental image of mourning, and point to immense feelings: ‘one goddess / in the sunlight of another’. Potent lines like this fill out much of the long poem ‘Persephone at 40’. Aside from one cheeky moment where Persephone takes pleasure in seeing another (Eurydice) suffer her own fate of eternal life in the underworld, the poem is austere, turning to classic themes with little innovation, flaws or tics – the seasons: ‘Ah, Winter, season of my mother …’ and solitude: ‘My mother cannot guide me / my husband ignores me’.

By contrast to the deities, White looks at human life and motherhood as being defined by its finitude, and made meaningful by it. While Persephone sooks: ‘I could love her more if I knew she would die’, humans ‘pray and cry and do all that’. Persephone’s mother is philosophical:

Tell me what a mother is, tell me for I do not know. Is it a ghost, a wound? A nothingness, an echo, as when she sang into the cave to hear her own voice--

‘Demeter’s Song’ is a dark nursery rhyme for adults, a quality echoed in ‘Mother On Men’, which begins with (and repeats) the annoying phrase: ‘Mother what is a man?’. ‘Demeter’s Song’ has only four more short lines which mirror the first four. We might think (concretely) of the bottom quatrain as the underworld, Demeter calling down:

for a huge-headed mother a sweetness hard to bear. Sing to me daughter, upwards through the darkness’.

This poem, like most of the very consistent Cities, trades in familiarity: ‘darkness’, ‘sweetness’, ‘mother[s]’, ‘ghost[s]’, and the extended universe of Greek myth. It has an aphoristic quality that holds the promise of profundity, wet-eyed, important.

We are a long way from cities, or, cities as we conventionally think of them are a distant backdrop. The city is figured as a mass of atomised grievers, who share stories, and together build the places we know as London, Berlin, etc. The poems, if they take place in the city, capture life inside it through a fisheye lens, everything around the speaker blurs and moulds to the centre, the speaker’s bug-eyes pleading, as in the obscenity of lines like ‘Sing to me daughter’. This language can never be broached in an actual city. To grieve, White shows, we have to turn to Poetry, away from the city. We have to write ‘To My Mother’s Ghost’. White affirms the power of art, but the actual writing to the ghost, ‘the numinous one’, is stylised and troped. It makes little use of the actual potential of poetry: ‘If you were down there / in the underworld I would look for you.’

There is so little flashiness, to a degree that feels sort of bold. Duwell lauded White’s ‘nothing superficial’ but I crave that – one quick thrill was the appearance of a chicken shop in a poem’s title, but you don’t feel the particular ambience of a chicken shop in ‘Chicken Shop’ so much as the platonic ideal of a place where you might accidentally leave your daughter behind, as the poem goes on to imagine, which is sort of funny actually, that ‘analytical’ mode of writing about a chicken shop. White is not eager to charm or flatter her audience. The difficulty produced by these unplaced, undetailed poems (in part I and II) suggests an attempted universalism.

Maybe I need to peel back. White’s caginess and ‘analytical’ mode must be partly due to the project’s personal nature: the grieving of her mother. Myth is a kind of self-protection; I feel inoculated from the grieving. So I’m left with the sense these poems voiced by ‘universal’ figures will never cut through to deep feelings. That is not their aim; their aim is to cloak grief in order to memorialise it. Sometimes White’s lines cling to cliché as a result, renouncing poetry’s duty toward inventiveness: ‘a mortal knows – / what you love you must lose. / But accept it? / Impossible as breath / under water.’ Cliché is not necessarily a bad thing. It can be good like a good pop song is good (a matter of opinion?). It can signal a timeless way of looking and acting (‘What I did, a mother would do’), and from this position, White makes lovely lines ‘… if I could hold / like flesh the empty air’. But is it bad to say: ‘What I did, a mother would do’, to speak timelessly, as a / the mother? This is an example of the conservatism of Cities: White is not signalling the fact that she is doing a critique of her own language while writing, and she writes to make sense by utilising familiar ideas and easy to understand ways of understanding those ideas.

I love White’s rejection of ‘rupturing language’ in theory, but find it alienating in practice. Occasional bursts of realism don’t help much. Anecdotes like ‘when she was a seventeen-year-old pantomime actor / and bowed to dark applauding space’ feel more like a stock photo than something living and breathing. Sam Langer, reviewing White’s second collection for Arena, referred to it as ‘honeyed’, both preserving technique and aesthetic gloss. Langer suggested the poems in The Simplified World demand ‘decod[ing]’. In Cities, any ‘private messages’ are to remain private, the poems less puzzles than prayer. They wear their meaning on their sleeves:

And at home I listen to the baby’s planetary breathing, each breath a second of her life and mine the impossible love that loves her every second.

Petra White stands out in that a lot of Australian poetry is so tongue-in-cheek when looking at canonical themes. From John Forbes to Evelyn Araluen, many Australian poets share a desire to defile the sacred myths of the west, an impulse White doesn’t have. Her poems are porcelain treats. These treats are part of a city, but don’t attempt to reproduce the feeling or image of a city. Why is White so far from the street, the workplace, the agora? In Cities, the real cliché is the hustle and bustle of avant garde art, from which the author turns. Nothing breaks: ‘For My Daughter Ten Weeks Old’ conserves the life of the baby, ‘Slumber in my wolfing gaze …’ She presents maternal relationships as if they were timeless:

Dark spirits of motherhood come with gifts of frailty, they say I will suffer, and fail, and you will not forgive me —