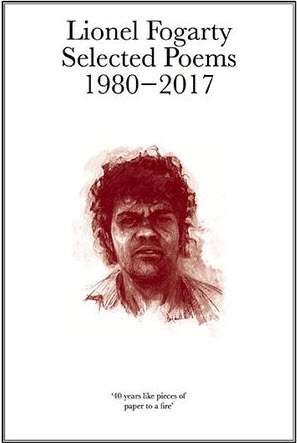

Lionel Fogarty Selected Poems 1980-2017

Philip Morrissey and Tyne Daile Sumner, eds

re.press Publishing, 2017

To begin this review, I would like to make the most important of declarations and acknowledge the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation as the traditional owners of the land on which this review was written; and would like to thank Narungga scholar, writer and poet Natalie Harkin for having assisted in the editorial process. I would also like to acknowledge and pay respects to Lionel Fogarty, the Yoogum language group from South Brisbane, and the Kidjela people of North Queensland, whose inestimable linguistic, cultural and spiritual legacy is clear in Lionel Fogarty Selected Poems 1980-2017.

The publication of this collection marks a retrospective moment for the Australian literary landscape. Lionel Fogarty, born in South Burnett in Southern Queensland, is a poet praised by John Kinsella as ‘the greatest living “Australian” poet’ (2013, 190). The controversial writer, Colin Johnston, also described Fogarty in 1990 as ‘Australia’s strongest poet of Aboriginality’ (26). (Colin Johnston is also known by the name of Mudrooroo, or Mudrooroo Narogin, an act that is seen by many as a misappropriation of the Nyoongar language.) I mention Johnston’s voice above many more fitting critics in this review to juxtapose Johnston’s and Fogarty’s fortunes in the last two decades as somewhat of a tragicomic mirror of the Australian literary landscape and our need to seek out an ‘authentic’ indigenous Australian voice. I write in heed of the deeply tenuous position Johnston occupies in Australian literature as explored by Anita Heiss in her book, Dhuuluu-Yala: To Talk Straight (2003). Heiss posits that from the time of Johnson publishing of Writing from the Fringe: A Study of Modern Aboriginal Literature in the early 1990s, ‘he was regarded as the authority on Aboriginal writing, and anything associated with it’ (4). When Johnston’s authority to speak on Indigenous Australian issues came under question in the years to come, the fallout regarding his lack of consultation and misappropriation caused an indelible impression upon our conception of indigeneity. Such debates over identity politics and cultural authenticity have changed how we read the work of Indigenous Australian writers – creating an obsessively objective distance that misleads us from the real conditions of writing, as well as obscuring the literary production of unabashedly indigenous voices. I would argue that this is certainly the case with regards to Lionel Fogarty, one of the most unrewarded and unrecognised figures in Australian and World Literature.

In Fogarty’s poem, ‘Finalist Unnamed’, a previously unpublished work included in this collection, he writes satirically of his omission from the ‘honour-roll’ of literary prizes: ‘My name is now the finalists unnamed? Ha’. The irony in these lines speaks to Fogarty’s imagined opposition to white Australian society, as well as his management of the distance between himself as an Indigenous Australian activist from the literary community. These seeming tensions reflect many of the frailties of the Australian literary landscape; the inability for indigeneity to be properly conceived of and read adequately in mainstream literary landscapes and markets, the literary-suicide of labelling oneself an ‘activist and poet’ to a wider Australian readership, and further, a lack of proper close engagement with Fogarty’s poems themselves. This review intends to grapple with these incongruities and signal, perhaps ambitiously, a trail that leads in to Fogarty’s nebulous, and yet, capacious collection.

The editors, Philip Morrissey and Tyne Daile Sumner, have collated both published and previously unpublished poems. The latter have been edited and published with close involvement from Fogarty himself. In this manner, Fogarty’s involvement as a co-editor and poet answers Peter Minter’s call for ‘a renewed ethical and aesthetic architecture’ (2013, 157). The poems are ordered in distinct periods where Fogarty was said to be particularly prolific: 1980-1995, 2004-2012 and 2013-2017. While this periodisation of Fogarty’s works may run the risk of emphasising perpetually relevant concepts (such as deaths of Indigenous Australians while in police custody or political representation) within discrete periods of production (many of the themes, phrasings and poetic rhythms are returned to, after decades), this structure offers a chance of seeing Fogarty’s images and turns-of-phrase evolve. This is particularly true of the 1980-1995 poems, a period described as a ‘high point’ for Fogarty while working alongside one-time partner, co-editor and publisher, Cheryl Buchanan, of the Kooma Nation in South Queensland. Buchanan’s work as an editor and publisher is significant for this section. A leader in her own right, Buchanan almost single-handedly published Fogarty’s first volume of poetry, Kargun, in 1980, stating in the official launch of the Yoogum Yoogum collection in 1982, that no publisher wanted to touch such ‘heavy political material’ (n.p.). It was her belief in Fogarty’s revolutionary style of writing as speaking rather than writing that moulded these poems, laying the foundation for his future work. In the foreword to the Nguti collection published two years later (1984), Buchanan would state: ‘Lionel regards himself as “a speaker, not a writer”, and does not like to be categorised as a “poet”’ (n.p). This sense of frustration against the identity of a ‘writer’ pervades Fogarty’s earlier poems. That is not to say that Fogarty’s poems can be read as discrete, singular entities. For instance, the demands of activism that pervade his earlier work transform into renewed decolonial thinking in the areas of education, Trans-indigenous solidarity and the historicising of Indigenous Australian activism. In this way, Fogarty performs a metaphorical encircling of his own position, what the Martinican theorist Edouard Glissant described as a reconstituted echo or a spiral retelling’ (1997, 16) regarding his own returns to earlier works. Morrissey himself notes that in revising each of the poems into English for publication, ‘the selection process has been complicated by Fogarty’s habit of revising and recycling sections of poems’ (Morrissey 19). As readers, then, we are privy to the forming up of Fogarty’s oeuvre in real-time. Such a re-processing, a spiral retelling of language-events, makes this collection of poems doubly worthwhile.

A reader might perceive, for instance, that the metaphorical implication of ‘death’ in the early poems – for instance in ‘Do Yourself a Favour, Educate Your Mind’ – differs greatly to the later poem, ‘Signing My Death Lionel and Hell’ (another example might be his variance in using the word ‘academic’ as the collection draws on.) In the former, ‘death’ acts as a metaphorical removal of Anglicised Australian identity imposed upon Fogarty in his being brought up in Cherbourg Mission: ‘(I) wrote my death in/George the Third’. In the latter, Fogarty imagines himself as a dying lion, Lionel literally translated to ‘Lion and Hell’ in order to convey his cyclical rebirth in the natural world, dying as a physically embodied writer, but eternalising himself through the potentially infinite re-readings of his works:

With my thousand words the dead woods are white dreams. Whistle the dead calls at morning night and depart away my spirit. Starless days are able to shine death, as rouse is use for me to die […] Listen it’s time for me as a writer to die.

Another way of perceiving the poems in the structure the editors have placed them is by transposing Fogarty’s poems alongside the political events that helped to shape them. For example, often the themes and motifs of his poems are direct references to news articles and current events, as a metaphorical (and at times literal) pastiche of contemporaneous jargon. This is evocatively evident in the composition of the unpublished poem, ‘Academic Great Boundaries’, which reflects on the water policy in the Murray Darling Basin and the dams that stop the water flow. In the poem itself, Fogarty metaphorically conjures up a dam wall through juxtaposing a self-authorising scientific vernacular divorced from feeling with his own intuitive writing:

Governments and nunnery highlands lie 49,000 bores lowering the table pastoral Non-flowing rate of 3% per annum.

In contrast, Fogarty alludes to the lack of benefits locals receive from the dam itself, remembering the incongruity of earlier colonial excavation of the land that eliminated native Australian flora and fauna. He questions the reader:

Are departmental shrubs destroying the remade reports? Is every central country plain without pains? Eliminate all inappropriate species The fallacy of the first dugouts Sunk in marbled stone.

It is also worth recounting the poet’s formative experiences, as they are at times presented, disfigured, in Fogarty’s poetry. For example, it is impossible to read his works without knowing of his politics. After growing up in Cherbourg Mission and becoming involved with the Brisbane Chapter of the Australian Black Panther Party, Fogarty was charged and arrested for demanding money with menaces and was detained in an adult prison while still legally a juvenile. Despite being acquitted for a lack of evidence, the experience remained with Fogarty and was recorded in a provocative account of his arrest in the poem entitled, ‘Related: Charged’:

Welcome here, you son of a cunt, This pig said to me. Sign your death warrant, you son of a fucken moll. Next released on bail

The crucially formative event of Fogarty’s adult activist life was the tragic death of his brother, Daniel Alfred Yock, a talented painter and dancer murdered under police custody in Redfern. This prompted some of Fogarty’s finest elegiac works, as well as some of his more charged political statements. Side by side, the 1995 poems ‘For Him I Died – Bupu Ngunda I love’ and ‘Murra Murra Gulandanilli- Waterhen’ can be read as a most profound expression of grief.