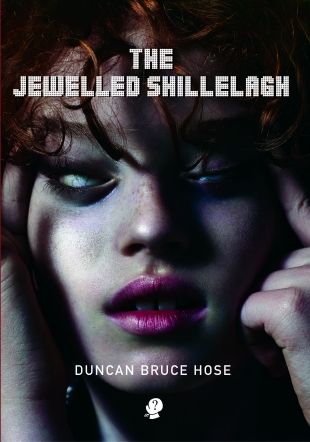

The Jewelled Shillelagh by Duncan Hose

The Jewelled Shillelagh by Duncan Hose

Puncher & Wattmann, 2020

‘HELLO FAERE CUNTIES!’ we are hailed in the opening lines of this rough-and-tumble volume, which swings between the campy and the choleric, the vatic and the venereal. The voice is sometimes that of a feral troubadour with pretensions to the lordly libertinism of Rochester (that ‘witty equivoque’):

Being too Bastinadoed for dancing tonight I’ll take my intol’able pleisure right here. Would you rather get plucked off by elsa martinelli or watch sian roarty clear a little bit of your warm live shot from her lip?

—at other times that of a poet-shaman evincing an Artaudian fascination with pagan cosmology:

It is the season of Xipe Totec (Sheep-he To.tek) Our Lord the Flayed One

Alive to the tiniest thing by being ritually turned inside out

In all dead forms the impersonator of life ...

A shillelagh is, as the back cover informs us, ‘a blackthorn club used variously as a walking stick, a companion, and a weapon’. Accordingly, these are combative poems and the ‘haranguing quality’ that Hose (who is also a literary scholar) has detected in John Forbes’ work (‘one is always being upbraided, or at least addressed’) provides a key to understanding his own. This poet does not mean to leave his readers alone:

I ought to take my wages in kisses I know bot

Headbutts are the major bullion

So come here ............

The tone of companionability edged with aggression closes the possibility of a polite distance between addresser and addressee. Hose’s shillelagh is thus an emblem of not only the rhetorical efficacy of his poems, but also their distinct modes of sociability – modes which reach both higher up and lower down the social order than the conventions of bourgeois respectability. We are as liable to be challenged to a chivalric duel as we are to be honoured as a fellow denizen of the demimonde (or simply another person on the pub crawl), but we are never allowed to settle comfortably into the position of the gentle/genteel reader.

Hose’s verse – what he dubs ‘Duncanpoiesie’ – takes some getting used to. It is wildly discontinuous in ways that the poems themselves seem to recognise: ‘Certainly what we see in operation is the Science of Motley’; ‘Mixa:mitosis ought to mean thinking and making in a ragedy fashion / Thinking in rags’. The raggedy edge of Hose’s wit makes ‘a sonic riddle for the human voix’ pulled in one direction by an appetite for rhetorical extravagance (‘-GET THE GOLD- I tell my disciples / Open up the ancient blue jets of rhetoric’) that brings to mind the pungency of Carlyle (‘Our fervid bio-squalor burned down to n egg-cup’s worth of snuff’) and pulled in another by a fidelity to the cadences of demotic speech:

Feelin so bolshie which means being

Like an uppity peasant as felt

By the Bourgoisie

Like the fat fuckin farmer who talks tender

To his workhorse

O’er the phone (Yr. a darling)

The erratic orthography and dynamic page prosody are crucial to the disheveledness – ‘a little shabbois (de- shabbie)’ [déshabillé?] – of Hose’s characteristic pose; they also contribute to an implicit privileging of the contingencies of oral performance over the fixity of the published text. The sheer pleasure of phonemic drift (‘Begatten Begettin Begotten’ or ‘Betelgeuse … Betelgeux … Betelguise’) in these poems is a testament to the vagaries of pronunciation and the richness of such imprecision (especially at the mongrel linguistic intersections of the Arabic, the Romanic, and the Anglo-Celtic). So is the unpredictability with which words such as ‘Bunratty’ are spelt (is it with one, two, or three ‘ts’ this time?) All of this means that Hose’s lines are more easily memorised and recited than transcribed with exactitude on the page, and it is with specifically oral traditions of songcraft that Hose is prone to associate his ‘chanteys’, which channel both the sea shanty and the medieval chanson.

While bracketing the obvious stylistic differences, it’s useful, I think, to consider Hose alongside PiO; these are two poets who consciously position themselves outside the mainstream of Australian poetry and one significant way in which they do so is by aligning their work with genres of oral performance. Long considered the doyen of ‘performance poetry’, PiO has nevertheless pointed to the parochialism of such a label when it overlooks its connection to one of the originary practices of Western poetics, namely, the recitation of Homeric epic by itinerant performers called ‘rhapsodes’. Hose’s work can also be considered ‘rhapsodic’ – not in the Homeric sense, but in the early modern usage of the term to mean a compilation or medley of verse riddles or slang rhymes. Rhapsodies such as The Hye-way to the Spyttel-House (composed in ‘cant’ or criminal jargon) and the Bannatyne manuscript (an anthology of medieval Scots verse) tapped into the obscure and sometimes disreputable registers of the vernacular, their linguistic esotericism tied to their speakers’ social marginality. In his study of lyric obscurity, Daniel Tiffany observes that in addition to an aesthetics of the miscellaneous, ‘the rhapsodic paradigm encompasses … various recurring waves of “indigent” poetry’ including ‘infidel oaths, thieves’ carols, beggars’ chants’ which ‘present a side of the rhapsodic tradition associated with profanity, malediction, and enchantment’. Compendia of shady language, rhapsodies record the songlines of a maligned if at times malignant shadow society.