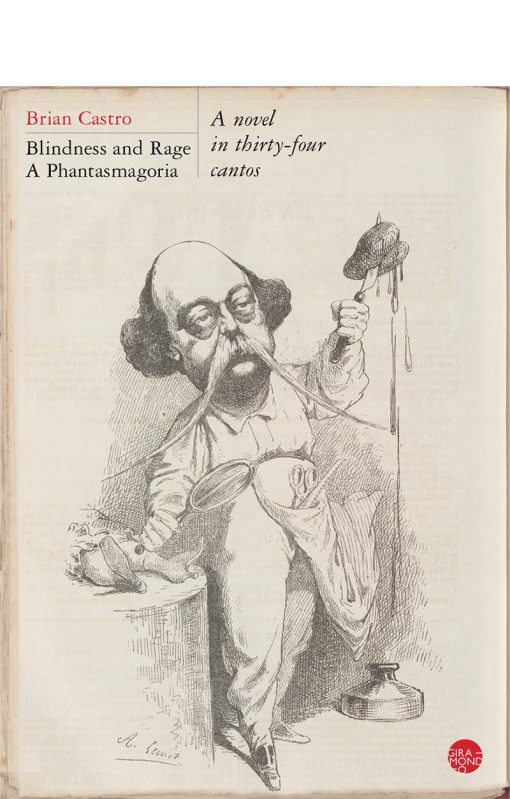

Blindness and Rage by Brian Castro

Giramondo Publishing, 2017

Blindness and Rage is the latest addition to an oeuvre that has established Brian Castro as a prodigy of hybridity. Castro’s heritage (Portuguese, Chinese, and English) is as uniquely mixed as the generic categories of his work, such as the blend of fiction and autobiography that won him such acclaim in Shanghai Dancing (2003). Blindness and Rage, at once ‘a phantasmagoria’ and ‘a novel in thirty-four cantos’, reprises some familiar themes in Castro’s signature style: a cosmopolitanism that shuttles restlessly between Adelaide, Paris, and Chongqing; the ludic propensities of an inveterate paronomasiac who wears his learning on his sleeve; a fascination with the vocational archetypes of the writer and the architect.

Blindness and Rage tracks the fortunes of Adelaide town-planner, Lucien Gracq, who moves to Paris after being diagnosed with cancer to dedicate his remaining days (53 on the doctor’s count) to completing an epic poem, Paidia, inspired by Roger Caillois’s 1961 sociological study Man, Play, and Games. Once in Paris, Gracq makes the acquaintance of the members of Le club des fugitifs, an all-male literary coterie that devotes itself to the anonymous publication of works by the terminally-ill. Epicures of self-erasure, the Fugitives raise the Barthesian thesis about the ‘death of the author’ to the level of a civic-minded mantra:

A named author dead or alive limits with fame the cancerous spread of signification; dead or alive, the named are pilferers of status, guardians of unequal truths, wrecking the liberty of recomposition. (107)

So says Georges Crêpe, frontman of the Fugitives, who are clearly modeled on Oulipo, the group of postwar French writers and mathematicians who set out to enlarge the prospects of ‘potential literature’ by tightening its compositional constraints. The other side of this ‘liberty of recomposition’, then, is ‘a ligature strangulation of meaning’ (142) so that what the Fugitives practice is, one might say, a kind of verbal chemotherapy. A not dissimilar point is made rather sharply by Catherine Bourgeois, Gracq’s concert-pianist neighbor who has her own ambivalent relation to the group:

They all suffer from vowel cancer— it’s a male reflex to constrict language; something to do with the castration complex. (142)

‘Vowel cancer’ is an uncharitable moniker for the lipograms with which Georges Perec (perhaps the most well-known member of Oulipo) is most readily associated, though it is the letter O rather than the E programmatically omitted in Perec’s A Void (1969) that gets disowned (in theory) by one of the Fugitives as a ‘damp squib/ defusing the presence of the I’ (92). This anxiety about the O’s dissipation of the potency of the I is a graphic joke about the ‘castration complex’ in which the author’s very name is made complicit. Indeed, playing with names has become customary in Castro’s bag of tricks; not only is Crêpe an anagram of Perec (as a number of readers have pointed out), but Catherine’s initials (with ‘the slot above her letterbox/ listed “Bourgeois, C.”’) continue the pattern of mirrored identities in Street to Street (2013), where the fictional Brendan Costa haunts and is haunted by the work of the Australian poet Christopher Brennan.

For all its immersion in the heady atmosphere of what we might call (very roughly) postmodern poetics, Blindness and Rage recalls an earlier moment in twentieth-century verse experimentation: high modernism. While Kafka has exerted a consistent influence on Castro’s work, the decision to structure his novel in ‘cantos’ inevitably calls up the ghost of Ezra Pound, a fellow observer of ‘Cathay’ whose obsession with paideuma (an ethnological term denoting ‘the tangle or complex of inrooted ideas of any period’ of culture) is at the very least etymologically entwined in Gracq’s pursuit of paidia (the Greek word for unstructured or spontaneous play).

With its lyricism peppered heavily with a magisterial garrulousness, Blindness and Rage in tone and texture most closely resembles some of the more personable moments in the work of the late Poundian, Geoffrey Hill. Like Hill in The Triumph of Love (1999), Castro sometimes deploys puns that just about stave off the literalist banality of the ‘dad joke’ through the charm of the poet’s contingent relationship to his own erudition:

[I]n Australia we play possum. Possum; because I am able to be a surrogate for myself; call it a mortuary aesthetic. (202)

This slapdash appropriation of Latinate prestige savours of an Antipodean egalitarianism that finds another outlet in the figure of The Dogman, a former high-rise construction worker who, after an accidental brush with an electric cable, now sells puppies and The Big Issue in an Adelaide mall. At one point he asks Gracq rather disarmingly: ‘what is this thing/ called deconstruction?’ (156)

As an embodiment of the hybridity feverishly imagined in various guises throughout the story, The Dogman is a totemic figure for the eclecticism of Castro’s enterprise in Blindness and Rage. A mixture of earthiness and ethereality, he conducts the novel’s energies away from the indulgent self-mortifications of European decadence towards an equanimity that is equal parts Eastern mysticism, Southern pragmatism, and animal indifferentism. After such exhaustive and (at times) exhausting cleverness, this equanimity is the closest that Blindness and Rage comes to a genuine touch of transcendence.