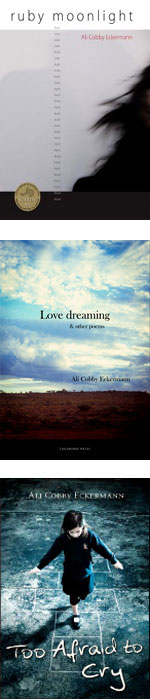

ruby moonlight by Ali Cobby Eckermann

Magabala Books, 2012

Love dreaming & other poems by Ali Cobby Eckermann

Vagabond Press, 2013

Too Afraid to Cry by Ali Cobby Eckermann

Ilura Press, 2013

Ali Cobby Eckermann’s work offers us a compass to our past and present. In poetry, memoir and verse novel, she maps a journey of Aboriginal identity and the historical and contemporary challenges to its integrity and resilience. What emerges is a profound engagement with healing and the articulation of Aboriginal space as always present, alive, intruded upon but utterly felt. She renders legible how ‘Footprints don’t fade / Culture / Kami May’ (‘Mai’, Love dreaming & other poems).

Both her collection of poetry Love dreaming & other poems and her memoir in prose and poetry Too Afraid to Cry explore a personal journey of reconnection to her Aboriginal identity. Although they traverse similar territory, Love dreaming & other poems is more public. While it deals with her relationship to her Aboriginal family and country, it also lays bare the Federal Government’s 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response, also called the Intervention, and its effect on Aboriginal autonomy.

Unlike these two works, her verse novel, ruby moonlight, published by Magabala Books, an Indigenous press, explores frontier contact between Aboriginals and Europeans in the mid-north of South Australia in the late nineteenth century. To speak of frontier is to ignore the reality of colonial Australia: space was wholly Indigenous and into this space emerged the white ghosts of ruby moonlight’s terrain to contaminate its integrity. Ruby moonlight demonstrates how first contact was a disorientation of violent intrusion and irrecoverable harm: members of a family group are murdered. Yet a subtle promise of co-existence emerges out of the trauma of a forbidden relationship.1

Across these three works, Cobby Eckermann articulates among other things the lived reality of Aboriginal presence in extended familial relationships and connection to country, notwithstanding the violent legacy of European disturbance. She traces a story of personal loss, trauma and reconnection in poetry and memoir, as well as a public story of political disempowerment, and a shared story of loss in ruby moonlight. She reminds us how Australian space, saturated in Aboriginal connection, suffering and resilience, has become a shared but troubled space between Aboriginal and European Australia – a space that isn’t necessarily emotionally recuperable as wholly one or the other. There is no remorseless anger or brutal self-pity, merely the deep cleft of history whose legacy is division but not defeat, since something is simultaneously remaindered and re-absorbed. As Cobby Eckermann says in ‘Circles and Squares’ (the poem appears in both Love dreaming & other poems and in Too Afraid to Cry) of her journey of reconnection to her Aboriginal kin:

I have learnt two different ways now I am thankful for this That is part of my Life Circle My heart is Round like a drum, ready to echo the music of my Family But the Square within me still remains The Square hole stops me in my entirety.

To read Cobby Eckermann with an attenuated attention to the experiential necessity of her Aboriginal identity is to experience displacement at the level of one’s own lived reality. This can amount to a double displacement among migrant groups attempting to negotiate their entry into mainstream society only to experience a strange sense of alienation as they confront an emptiness at the heart of settler society: its appropriation of a landscape to which it lacked traditional association, a lack it projected onto the country itself as though it were its lack, not theirs. Post-Mabo and post-apology, Cobby Eckermann’s work is as affectively political as it is strongly personal, since it addresses issues of our time, such as the legacy of separation policies and other paternalistic measures.

The sexual abuse with which Too Afraid to Cry opens, or the racism of the schoolyard, may be shared human dilemmas of trauma, but in refusing to collapse the distance between settler and Indigenous we can begin to absorb the necessity of the narrator’s reconnection with her Aboriginal family as a journey of the utmost healing and breakthrough.2 Too Afraid to Cry demonstrates the need for Indigenous connection to family and culture as an abiding reality that is necessary for what is after all a human right: the right to be with one’s family and people. This is not to insist on bankrupt notions of difference, racial or otherwise, but to acknowledge a broader need that cannot be quenched other than by the spatial enactment of connection to country and culture. As Cobby Eckermann says in ‘Hidden Water’:

there is love in the wind by the singing rock down the river by the ancient tree love in kangaroo, goanna and emu love when spirit speaks no human voice at the sacred sites eyes unblemished watch wedge tail eagle soar over hidden water find the love

In Too Afraid to Cry, Cobby Eckermann unveils the story of her reconnection to her Aboriginal family. It is a spare narrative whose economical language yields a concentration on the affective detail rather than the panoramic sweep. The story emerges slowly and painfully. In four parts, the poems interspersed throughout the narrative turn the text into a landscape of anguish and hardiness, hope and connection. The love of a white family, which is not in doubt, is not enough; the yearning is for a connection that can allow for a full blooming of the narrator’s Aboriginal identity.

The memoir begins in a child’s voice, darkening intensely until a voice of hope sounds. Cobby Eckermann’s journey of reconnection to her Aboriginal family begins long before she leaves home – in the way she is made conscious of her Aboriginal identity in the schoolyard, in the public outings with her white family, in the slim connections that she makes with other Aboriginals. To connect with her desire to find her Aboriginal family is to connect with a deep yearning. It is an absence that only reconnection can recuperate.

Late in the memoir, Cobby Eckermann describes being invited to attend Women’s Business on her grandmother’s land south of Uluru, with ‘dots of campfires … scattered across the meeting ground’. Without sentiment or rhetoric, she states that ‘it is a special place’. One of the women tells her that the despair and wailing that she hears across the sand dunes ‘are the Spirits of the people who died from the atomic testing at Maralinga’. Cobby Eckermann is told that ‘many of the Spirit people are my family’. She cannot stop crying. In dance and song around her, the women welcome her back to her traditional country and heal her. It is a powerful scene that highlights the need for kin, language and country and the particular spatialisation of Aboriginal life: the ceremony cannot take place just anywhere.

What makes Too Afraid to Cry a remarkable narrative of reconnection is the way in which Cobby Eckermann negotiates its painful territory without the dramatics of blame but with all the moral force of affective truth. Cobby Eckermann needs both worlds, but not one at the expense of the other; thus, she is ‘happy when my two families are together’. It is a narrative of political as much as personal hope that points to the future, as Cobby Eckermann experiences the richness of her extended Aboriginal familial connections, ‘turning the past hurts into healing’.

Some of the poems in Love dreaming & other poems also appear in Too Afraid to Cry. In total, there are thirty poems interspersed between passages of personal memory. Like points of reflection as much as emotion, they turn the narrative into a three-dimensional landscape of journey and reconnection, one that articulates the bewilderment of growing up Aboriginal in a white world that insists on exclusion, of growing up without the recuperation that lies with reconnection to her Aboriginal identity. The insistent question ‘But where you from?’ from a girl in the bed next to the narrator in hospital, a girl who looks a bit like the narrator’s big brother with ‘the same beautiful dark skin, darker than mine’, operates as an insistent marker of a necessary journey of reconnection which is intensified by the narrator’s experience of violent schoolyard racism and white adult condescension. Cobby Eckermann’s desire to be friends with other Aboriginal children she meets at her new school is a recuperative encounter, which signifies the original familial connection that is lacking in her young life.

- The work won the Kenneth Slessor Poetry Prize and the Book of the Year award in the 2013 NSW Premier’s literary award; it has also won the 2012 Deadly Award Outstanding Achievement in Literature; moreover, it was awarded one of the inaugural kuril dhagun Indigenous Writing Fellowships offered through the State Library of Queensland’s black&white project in 2011. ↩

- In The Postcolonial Eye: White Australian Desire and the Visual Field of Race (Ashgate, 2012), Alison Ravenscroft discusses how ‘reading practices based on identification risk collapsing differences’, suggesting that such reading practices do not address how things come to take their particular meaning (10). ↩