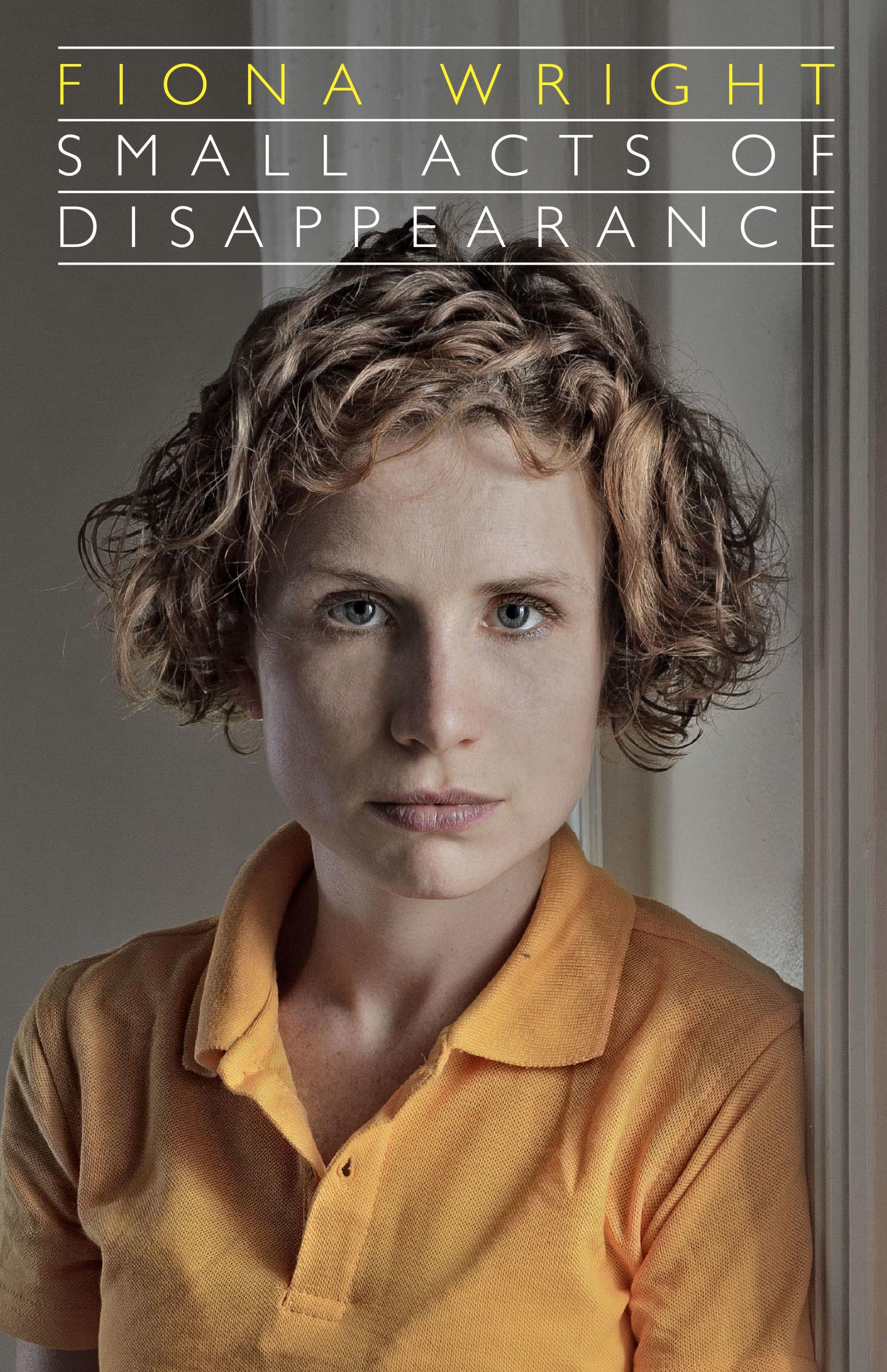

Small Acts of Disappearance: Essays on Hunger by Fiona Wright

Giramondo Publishing, 2015

The essay collection is a form that writers are turning to more often and no wonder, when the form offers so much potential, a potential totally realised by Fiona Wright’s Small Acts of Disappearance: Essays on Hunger. There are many things to admire in this collection, not least being the fact they defy categorisation.

All ten circle the theme of hunger and are ordered in a vaguely chronological fashion, but they also take on broader concerns, and seek to identify the points at which language, literature, love, illness and memoir overlap. Together these essays in form a consideration of the ways the body politic inhabits one particular body: the author’s.

In her late teens Wright developed a physical illness, which became a mental one. She came, over the years, to crave hunger. ‘Hunger is addictive, and it is intensely sensual, pulling the body between extremes of hyper-alertness and a foggy trance-like dream state.’ But when is hunger personal and when is it political? Sri Lanka, a country where the hunger of the people is ‘many-faced, insistent’ is a powerful place for Wright to begin her enquiries. Her first essay, ‘In Colombo’ is not just evocative of a place and a time (Colombo, 2006, three years before the end of the Civil War) but of the work that food does. It keeps us alive but it does more than that: it acts as a form of social cohesion. In refusing food Wright finds herself isolated not just from her self but also from society, at just the point when she needs to remain open, available and curious. Her hunger is beginning to shut her down.

Wright’s insistence on a wider view is particularly clear in the essays ‘In Book I’ and ‘In Book II’, which both discuss novels that have anorexic characters. Sometimes the illness is stated, but other times it is not. Here Wrights concern is to provide a critical reading of works where the author’s concerns might have slipped by, unnoticed. You need to look, she is telling us. To understand. One of those books was Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet, a book that I edited and had connected to intensely – yet I carried no memory of Rose Pickles’s to starve herself. I was shocked to be reminded of my erasure. There is also an analysis of Teresa from Christina Stead’s For Love Alone and Virginia from Carmel Bird’s novel quite remarkable novel, The Bluebird Café.

In her essay ‘In Miniature’ Wright considers the way tiny figures and objects cause both fascination and unease. The sense they convey that the world is out of kilter in some ways. One of the ironies that Wright touches on here is that her attempts to disappear herself make her loom larger. People cannot look away. And while this reader was relieved that some people noticed how unwell Wright was, one also feels frustration that the female body has no rights, can never hide itself, is always on display. Certainly these essays invite both projection and identification and I found myself doing both, remembering the admiration my appearance elicited many decades ago when I was ill and dangerously underweight. The cultural rewards of just the right amount of starvation.

While Wright has written these essays from a position of self-awareness, that awareness is hard won and remains in doubt until the book’s end. What does it even mean to recover? Who will she become? ‘I was so unwell that I only escaped forced hospitalisation because an administrator miscalculated my BMI, but I was also so deluded that I still thought, even at that point, that I was fine.’ While Wright is tough on herself she’s not excoriating. These essays are too good to take the route of self-flagellation and nor is she interested in the confessional mode.

Above all else Wright is interested in language and the writer’s work. Her poetic perspective helped her survive her illness in part because of her sense that writing and hunger come from the same creative place. But such perspective also encouraged disassociation. This is just one of the complexities Wright must navigate. Hunger endangers her but it also provides definition, both of experiences and of the self. ‘Hunger allows us to hold our potential as potential,’ Wright says, reminding us that hunger is an addiction like any other with its own compelling and insular, logic. One of this collection’s achievements is the way in which Wright conveys all this without romanticising anorexia. It is language, with all its seductive qualities, that kept Wright in her head out of her body and it is her return to embodiment – her greatest struggle – that language must be found for.