Immune Systems by Andy Jackson

Transit Lounge, 2015

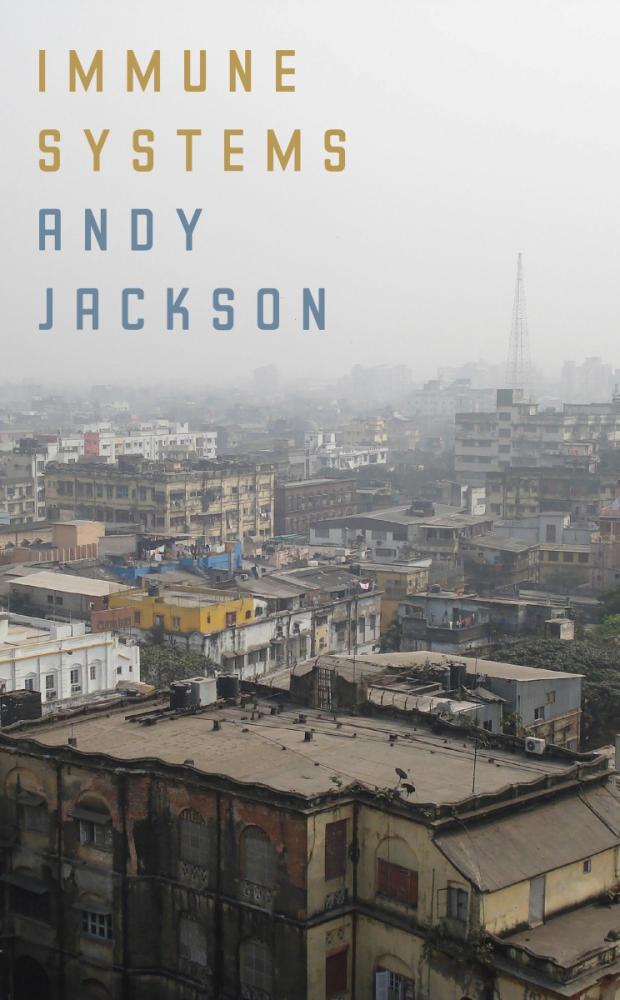

Andy Jackson’s viscerally potent anthology Immune Systems exposes the reader to the bloodline of medical India, where medical tourism leaves the general population battling fraught poverty and the medical afflictions which accompany it.

Tripartite in structure, the series begins with a verse novella which explores medical tourism with an uncanny and thought provoking lens. A series of quick witted haiku’s offering small dense exposures of humour follow, while the series ends in a suite of complex and lyrically engaging Ghazals.

Jackson uses the insights of poetry to blur the lines of the physical experience, dissolving the state of otherness which exists when rigid physical boundaries are used to establish a sense of self and other. Jackson demonstrates the personal body and the societal body of urban India, to be experiencing the same contingencies and complications. This allows the reader to establish an empathic solidarity for the portraitures and circumstances presented throughout the series, rather than generating feelings of sympathy and otherness.

Jackson attaches you to the beating transport – ‘ the heart of this city of millions’ (15) – with a warm touch which takes in and acknowledges the desperation of people, evolving a tourist experience beyond the untouchable and distancing ‘ clichéd images of India’ (11). Abject vagrant bodies are observed with an eerie silence as city noises are decomposed and images are evoked like a ‘light film’ (15) which settles over the eyes.

An intimate connectivity is developed Immediately as the boundaries separating tourist from local are scattered by the reflective mirror surface present in the anthologies first poem, ‘Apollo Hospital’. Beginning at a point of vulnerability, the sweat fuelled and panicked speaker searches skyward for a hospital – an emergent layer – amongst a population condensed within an unrelenting street level filled with ‘crushed plastic and food scraps’ (11). The skyline holds a ‘white and mirrored’ (11) luxury hotel. The hotel’s reflective state creates a symbolic socio-economic barrier which perpetually projects poverty back onto its own reflection. Whereas the non-reflective steadfast ‘white–grey’ (11) water of the canal – which the speaker passes on the way to the hospital – threatens to pull its surroundings ‘down [into its] … banks’ (11). With these images Jackson illustrates the post-colonised space which the poverty afflicted are forced to hover in between. Progression is left ‘unfinished’ (11), and medical infrastructure suffers; ‘a British surgeon gives up translating/ Ayurvedic texts’ (31). The speakers taxi driver later says ‘The British brought good things,/ but divided us, kept people uneducated’ (15). Taking this in the speaker ‘keep(s) walking’ (11) and instead focuses on the portraitures of people – observing them with a tender observatory gaze – without letting the ‘shocking/ clichéd images of urban India‘(11) amount people to a state of caricatured otherness.

Jackson breathes humanity into the societal body locked out of medical treatments and forced to live ‘in clusters of concertinaed flesh/outside the best hotels, the five-star hospitals’ (19). He uses space and rhythm to symbolically embody the state of the medical infrastructure in a man with ‘no legs … crossing the road,/ using his calloused hands,/ moving slowly towards the gutter, backwards/ [while] An autorickshaw honks in protest/or warning’ (31). All encounters are felt with a devastation, as the sense of normalcy with which ‘you just have to accept suffering’ (25) is felt like the bloody reports of ‘newsprint (staining) your fingers … black’ (14).

The language is hygienically simple and unflinching and, despite the haze brought on by the sheer density of desperation, the anthology does not shy from questioning the fraught system which perpetual cycles poverty.

The speaker’s anger emerges in ‘Whatever exists in the universe’ where statistics of ‘unlicensed medicine factories’ (33) cover a prose type space, while excerpts for medical tourism marketing sit neatly aligned and centralised attempting to cover the poverty fuelled edges;

India is an extraordinary destination, Ideally suited for recovery and unwinding after a stressful surgical intervention. Our after-care … (33)

Jackson turns a fraught interwoven society characterised by poverty into an ‘inverted jewel’ (17, Sadhu) through its efficacious portraitures. He skilfully demonstrates urban India as an intrinsically and inextricably connected body, characterised by ancient tradition and globalised entrepreneurialism. The series feels as intimate as a heat driven dream in the first few glossy moments of waking and ‘the sun is everywhere … swollen’ (22) and unforgiving.

Jackson forces poverty to be seen as a unattended wound, which despite ‘police/ resorting to batons to subdue’ (14), remains a festering limb infecting and disturbing the whole immune system of society; he refuses to let poverty be reduced to a phantom limb. Immune Systems raises pertinent issues about the effects of medical tourism on an already impoverished society, while its efficacious portraitures itch and stay with the body like a ‘mosquito’ (37) bite.