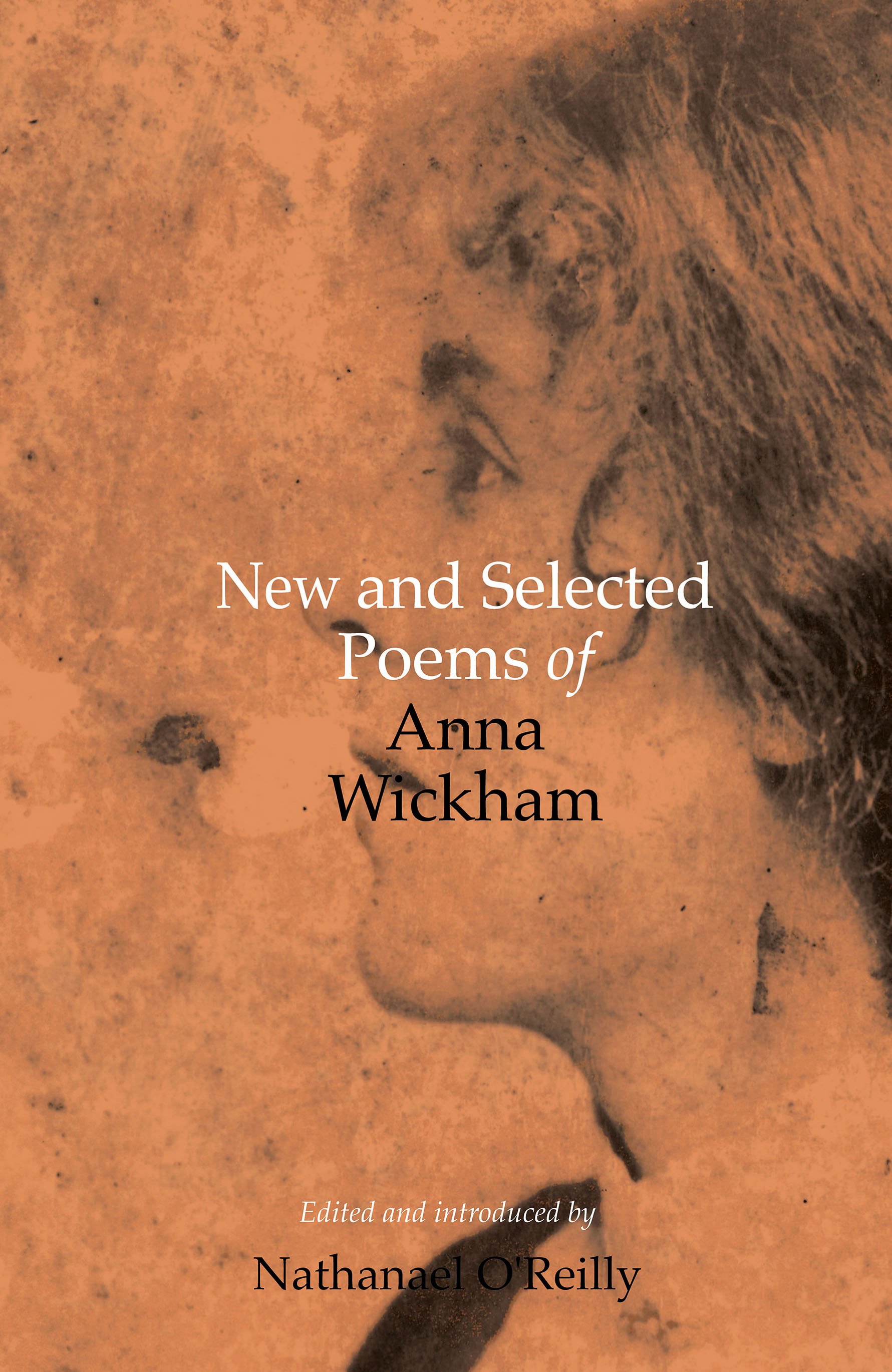

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham edited by Nathanael O’Reilly

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham edited by Nathanael O’Reilly

UWA Publishing, 2017

Devotees of Australian literature are unlikely to possess more than a half-dozen single volumes by poets born before Federation, and their reading of such poets is generally limited to anthologies. The problem, I’d suggest, is one of availability more than desire. University of Western Australia Publishing (UWAP) is one publisher looking to redress this through an intermittent series of titles, which include Lesbia Harford’s Collected Poems (2014) and the Collected Verse of John Shaw Neilson (2012), together with more recent classics, such as Francis Webb’s Collected Poems (2011) and the Selected Poems of Dorothy Hewitt (2010). UWAP’s latest volume is the elegantly produced New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham, edited and introduced by Australian-born, poet-scholar Nathanael O’Reilly, which republishes 100 poems from Wickham’s five collections together with another 150 previously uncollected poems.

The book’s short introduction provides a brief outline of Wickham’s biography. She was born Edith Alice Mary Harper in London in 1883, but lived in Australia for most of her childhood in Maryborough (Queensland), Brisbane and Sydney – taking her pseudonym from a Brisbane street. Wickham returned to London in 1904 to pursue a singing career and there she married a successful solicitor, Patrick Hepburn, who remained her husband for over 20 years. The marriage, which produced four sons, was unhappy, largely because Hepburn opposed Wickham’s artistic pursuits – in 1913 he had his wife institutionalised for three months. George Bernard Shaw, Dylan Thomas, Katherine Mansfield, Laurence Durrell and DH Lawrence were among her circle of friends. Having struggled with depression for most of adult life, Wickham suicided at the age of sixty-three, leaving over a thousand poems, most of which remain unpublished.

Among the work collected by O’Reilly are free verse and strict forms, monologues, sonnets and verse in ballad-metre, short chiselled lyrics of regular rhyme and metre, imaginative narratives and dramatic monologues, and some mixing of distinctly different forms. A reader is often struck by a deliberate asperity. Wickham asks in ‘The Egoist’:

Shall I write pretty poetry – Controlled by ordered sense in me – With an old choice of figure and of word, So call my soul a nesting bird?

The answer is a resounding no. Living in the age of aeroplanes, she reasons – in the line that resolves the poem and stretches to a comic twenty-one syllables – that she will write her ‘rhythms free’. The homely Georgian imagery of the opening stanza is not entirely rejected but the work is generally more direct than that of most of Wickham’s contemporaries – ‘Paradox’, for example, opens with the phrase: ‘My brain burns with hate of you’ – but it can occasionally be esoteric and obscure. It is an erudite poetry in a literary sense, steeped in the classical tradition, in Shakespeare and the Romantics. The content is often more radical than the forms, as she explores and interrogates gender roles, marriage and motherhood. Perhaps most modern of all, she celebrates the therapeutic power of poetry.

The strength of Wickham’s personality, and the power of the work is manifest in ‘Mare Bred from Pegasus’:

For God’s sake, stand off from me: There’s a brood mare here going to kick like hell With a mad up-rising energy; And where the wreck will end who’ll tell? She’ll splinter the stable door and eat a groom. For God’s sake, give me room; Give my will room.

The poem’s force comes not only from the equine imagery that Wickham often returns to but from a diction that is both rhetorical and colloquial. It is a charged language of strong verbs, spiked consonants and quick vowel sounds. The compound-adjective, ‘up-rising’, is particularly powerful, while the eating of the stable boy, or figuratively the husband, manages both to menace and charm. The repeated plea for ‘room’ is central to another of the book’s strongest poems, ‘Divorce’:

A voice from the dark is calling me. In the close house I nurse a fire. Out of the dark cold winds rush free To the rock heights of my desire. I smother in the house in the valley below, Let me out to the night, let me go, let me go.

Night is presented here, and elsewhere, as synonymous with the feminine and the creative. While the concerns of this poem are personal the imagery is, characteristically, elemental. We see the subtleties that Wickham is capable of in the adjectives ‘close’ and ‘rock’ and the verb ‘nurse’, the interesting use that ‘smother’ is put to, and the beautifully measured refrain. In other poems, Wickham prefers the role of the passionate lover to the dutiful wife, as in the ambiguous three-line ‘Function’:

I do not grudge you to your wife: but take a mistress And I'll have her life.

While the poet-speaker is resigned to dissatisfaction with marriage and concedes acquiescence to be the easier path, she refuses to be silent. The shrew is a trope to which Wickham often returns and, as the poet delighted in flouting social conventions in her lifetime, so the poet-speaker embraces this role with gusto.

In the poem, ‘Meditation at Kew’, which may remind of Thomas More’s Utopia, Wickham reimagines marriage. Written in rhyming couplets but set out in quatrains, it begins:

Alas! for all the pretty women who marry dull men, Go into the suburbs and never come out again …

Wickham goes on to lament the sufferings of such suburban women and, in contrast, presents a sort of Arcadia:

I would enclose a common in the sun, And let the young wives out to laugh and run; I would steal their dull clothes and go away, And leave the pretty naked things to play.

The dullness of the clothes the speaker steals picks up on the poem’s earlier uses of the word, which include the ‘old dull’ gentle classes, who ‘must breed true’. The sun contrasts the sterile drabness of the earlier imagery, as the looser spirit of play contrasts the passivity and stasis implied by the poem’s opening. In Wickham’s ideal the women are to see all the men of the world before they make their choice of partner, and the resolution that follows fuses Wickham’s critique of patriarchy and the class system:

From the gay unions of choice We’d have a race of splendid beauty and of thrilling voice. The world whips frank, gay love with rods, But frankly gaily shall we get the gods.

Though the wife-husband context suggests the primary meaning of ‘gay’ to be something like joyous or carefree, the term’s modern usage was becoming more common in Wickham’s lifetime, and this secondary meaning reinforces a subtext of lesbian desire.