Shaggy Magpie Songs by Murray Edmond

Auckland University Press, 2015

Murray Edmond is a New Zealand poet of long-standing achievement. He published the first of twelve previous collections, Entering the Eye, way back in 1973 with Caveman Press; the most recent was Three Travels (Holloway Press, 2012). He is a dramaturge, with a career ranging from the experimental Red Mole Theatre Company to the present Indian Ink Theatre Company. He was co-editor of the 2000 anthology Big Smoke: New Zealand Poems 1960-1975, which restored marginalised voices from the 1960s and 1970s, especially women poets such as Anne Donovan, Kathinka Nordal Stene and Christina Beer. He is now editor of Ka Mate Ka Ora: A New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics.

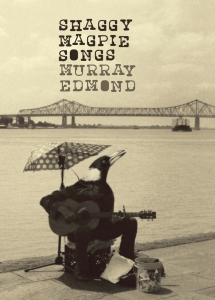

The front cover image of his most recent collection, Shaggy Magpie Songs fits its tone beautifully. A busker with an acoustic guitar and capo sits on two cushions balanced on a milk crate. Money is collected in an old paint tub. Behind him, an umbrella is attached to a microphone stand. The busker’s head is that of a magpie, looking upwards, purposively. He’s perched on the waterfront below Ponsonby near the Auckland Harbour Bridge. Insofar as the title acts as a premise for the collection, it’s a convincing one, as its thirty-four poems testify.

You can’t mention magpies in the context of New Zealand poetry without thinking of Denis Glover’s famous ballad ‘The Magpies’. In Edmond’s latest collection, the cadences of Glover are evident in ‘Mister Wat’ and in ‘Conversation with My Uncle’, even before the reference to Glover, or before encountering the back cover’s nod to this literary heritage. Edmond is not just making a reference but embracing elements of Glover’s style, rough-edged and profound.

Placing the concept of song lyric firmly in the centre of the collection sets up certain expectations but also aids the broader exploration of what might constitute a lyric, since the poems which have a less formal structure are read for their similar or different qualities to the others. In the rhyming poems, a firm pattern to the rhyme is not always detectable, but, importantly, the rhythms are compelling On the whole, the rhyme does not control the poem to the expense of all else. There are funny and original rhymes, such as ‘rode the railroad tracks of his undos’ with ‘choose’ and ‘shoes’ (‘Clown on Skates’); and there are elegant stanzas:

cook was scraping bones (thin soups are the best) for every Greek that groans there’s one who groans in jest (‘Swing Your Tiger’)

One is conscious of the rhyming sounds as simply another set of playful possibilities, rather than the rhyme becoming irritating because it is obvious or controlling, which is an all too common fault even in much published rhyming poetry.

Much of the book celebrates the ordinary. Ordinary moments, real or imagined, are shaggy ones, for example, graffiti described as being in ‘a young and scrawny scrawl’ in the poem ‘So-So Street (A Soliloquy)’. They recall Edmond’s quoting of Guy Debord in Then It Was Now Again – Selected Critical Writings (Atuanui Press, 2014), in which Edmond suggests that the poems in the Big Smoke anthology ‘constitute “fleeting moments resolutely arranged”’. They are fleeting here, too, and might go unnoticed but for the poet’s noting the situation. The understated ending to ‘With Jean-Paul Sartre on the Banks of the Waikato’ celebrates the ordinary even in the midst of a surreal scenario, as well as introducing ‘characters’ in a manner that reflects an understanding of dramatic potential. The poem ‘Painter Looking at Painting’ describes in the most pragmatic terms the way painter and painting form a relationship, and is beguiling in its mysterious ability to evoke an essential connection. ‘National Standards’ takes a satirical view of what I assume to be the proposal in New Zealand for single, unified courses for each subject at tertiary level, a kind of one-world curriculum; there’s something ominous and chilling about the poem which reflects one’s anticipation of such an homogenised educational strategy.

By contrast, the collection is not averse to something like the mystical, as these lines suggest:

your cousin tells you he knows a hole you can slip through to take a short cut it’s a portal to the thing you cannot imagine but know is there and the very idea of ‘short cut’ causes you to burst into relief for the relief it promises

Is this merely childhood play, or something more serious? Is mystical too strong a word? The text accepts each situation without judgment and suggests that the human spirit has ‘a certain flounce that never was seen before / in this universe’ (‘In the Purple Mists of Last Evening’); if anything is mystical or transcendent it’s us.

‘Forty-two Boxes’ focusses more purely, and adventurously, on language. Its diction is tight from the start, Curnowesque in its compression, but more playful:

dragon silk corn powder jade Buddhas with a gift for laughter green black and red phials of infused herbs

The poem is full of unusual words and connections, a microcosm of the whole, a time capsule. It’s not a poem to understand necessarily, but one with which to savour the aesthetics of language.

It is not only about language, of course; there is too much variety here, too much lyric and examination of the lyric that remembers song as close cousin and rhapsodises it, albeit in a suavely detached manner. In fact, one imagines the voice of many of the poems as shaggy, but in a nice jacket (‘a certain flounce’, above, suggests this thought most clearly). The poems embrace repetition, its use varying through a range of refrains, including one that could easily have come from the pen of A A Milne: ‘she points her little pinky oh she points her pinky / and points that pinky at the likes of you and me’ (‘Matataki, 1822’).

The extended sequence ‘Tongatapu Dream Choruses’ is a group of nine poems whose structures – from a loose prose poetry to short, haiku-like stanzas – showcase the diversity of musicality that well-arranged words can bring. Edmond has a penchant for hyphenated composite terms, for example, ‘reflected apocalyptic dreaming / from the One-and-Only-Will’ and the ‘Only-Lonely-Lonely-Only Ones’ (‘A Train Wreck in the Universe’). The compounding of the nouns has the effect of forming descriptions as well as musical jinglings which are refreshing, and show some daring in their arrangement of language in less familiar forms. The grammar of the poems often strays from correctness in useful ways, helping evoke the demotic, an element counterpointed with the prosaic, and sometimes with an unexpected sophistication. For example, in ‘Road Song’, the lines ‘now tell us who you are / now justify impetuosity’ contrast sharply with the everyday diction of the preceding stanzas.