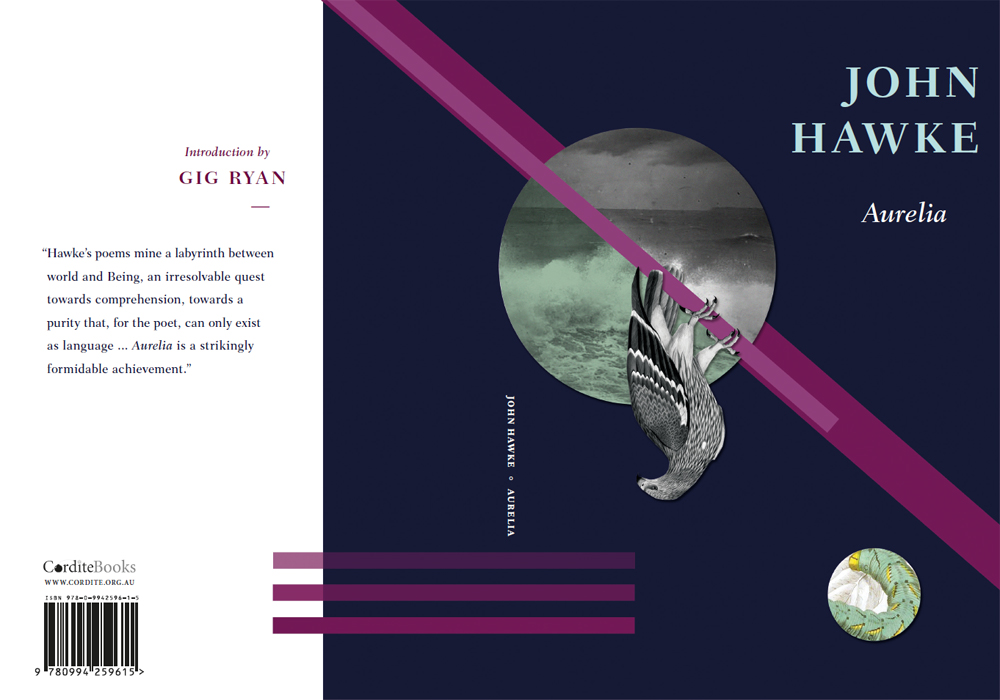

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

John Hawke’s forensic inquiries in this book are layered with casual erudition – Diderot, Czech poet Vladimir Holan – and locate the poem as transformative state. Many of these poems conclude with a mystical ascent into nature, reminiscent of Patrick White scenes in which the division between consciousness and the universe wavers, signifying that any reconciliation is epiphanic, claimed by art or religion. Yet nature belittles human effort – ‘The path to the point is marked by a scattering / of impermanent hand-made memorials’ – that is, the poet’s endeavours are precariously, though heroically, makeshift, overlaid; but nature is also that which threatens or devours, ‘digesting light’.

The title poem alludes to Gérard de Nerval’s prose poem ‘Aurélia’, which begins ‘Le rêve est une seconde vie’, in which the desperate poet sees the universe as a giant alphabet – inspiring Baudelaire’s later ‘Correspondances’ with its ‘forêts de symboles’. (Nerval in 1854, the year Rimbaud was born, wrote ‘Je suis l’autre’ beneath a photo of himself). The spectral Aurelia symbolises yearning for completion, her image embodying universal truth, a theory-of-everything, which the poet can only glimpse. Aurelia is a manifestation of art – ‘I first fell in love with Aurelia / in the face of that woman painted by Giovanni Bellini’ – that is, love clasps the actual simultaneously with its ideal, just as Proust’s Swann imagines in embracing Odette, he embraces Botticelli’s Zipporah whom she resembles.

and we enter that forest of symbols where everything coincides. These correspondences find their relation in the name of the absent beloved, as if the world of visible signs were itself a vast and scattered alphabet ...

This book’s tour de force is its longest poem, ‘The Conscience of Avimael Guzman’, a scrutinising cubist portrait of Peru’s Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) leader, which begins with this former philosophy professor strangling a woman. Justifications gnaw and collapse into a weird crescendo of turbulent ambivalence.

The strings of your nerves drawn shrill by the need to maintain a single extreme moment, but that was an error, a point of mathematics: better to proceed by denial, eating your own words, phrases compacted and swallowed in gutters. The fabricated voice of the journals dissolves behind you ...

Hawke’s poems mine a labyrinth between world and Being, an irresolvable quest towards comprehension, towards a purity that, for the poet, can only exist as language. Plated with consonance through quasi-rhymes such as the end words in ‘Early Spring’ – ‘leaves, anemones, bees / hips, imprinted / stream, eel / step, breath / planet, radiance’; ‘Link Wray’ and ‘lisping rain’ in ‘Halley’s Disappointment’ – Hawke’s descriptions are as fastidiously observed as Kenneth Slessor’s or Robert Gray’s – ‘tea-coloured river’, surfers ‘skate / across the lucid skin of a dangerous break’.

In other poems such as ‘The Police-spy As an Owl’, Being, exiled from transcendence, is submerged into its activity, ‘Only productive things have meaning … it is use / which defines’; this also reiterates an earlier poem – ‘the artist’s signature / which is death’ here becomes literally ‘His signature is death’. There is a vast array in these lucent metaphysics, from the ominously Oedipal ‘On Woodbridge Hill’ to celebrations of children and love in ‘Early Spring’, ‘The Night Air’ and ‘Emily Street’, to the satiric or even apocalyptic ‘The Poet Speaks’. Hawke’s much-awaited Aurelia is a strikingly formidable achievement.

Pingback: Various lockdown hacks and escapes — 66 — Glebe, Neos, John Hawke: poet | Neil's Commonplace Book