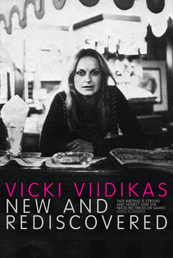

Ali Alizadeh: Could you talk about your decision to edit and publish Vicki Viidikas: New and Rediscovered? What's significant and exciting about Viidikas and her work?

Barry Scott: I first came to the writing of Vicki Viidikas through the prose poetry collection India Ink (Hale and Iremonger, 1984) and was so moved by her approach and subject matter that I quickly sought out her other three books, Wrappings and Knabel (Wild and Woolley) and Condition Red (UQP) all published in the seventies. A shared interest in India and spirituality can only partly explain the magnetic pull her writing exerts over me.

Vicki was drawn to outsiders and the empathetic way she writes about them could only come from someone who at times also felt marginalised and outraged at the way people who were individual or different could be ostracised. ‘I gravitate towards people who are misfits or trying to be themselves,' she said in a 1975 Vogue interview. For Viidikas writing was an emotional, intuitive act, often confessional but always carefully honed and realised.

While she often stated that her writing was not intellectual, it is intelligently crafted. There seems to be an impression in some circles that she wrote quickly and never redrafted which is dispelled by the extensive archive of her work that exists in manuscript form. The lengthy story ‘Cretan Boy, Sailor Free' published in New and Rediscovered for the first time, is further evidence of her fiction writing powers and her ability to write about sexuality and relationships in a way that was both perceptive and truly brave.

Writing well about emotions, male and female relationships, and the spirit is risky business, but Viidikas does it without sentiment and without aligning herself to contemporary theories and structures such as ‘feminism' and ‘political protest.' When asked in Vogue if she would be interested in writing protest poetry or social criticism Viidikas commented, ‘Writing a poem about the Vietnam war would be a futile gesture. Real value comes from personal experience. I am interested in personal truths for the poet.'

In the ABC Radio National broadcast ‘Feathers/Songs/Scars' produced by Robyn Ravlich, a fellow poet and friend of Vicki, Robert Adamson described Vicki's writing as ‘organic, holistic, courageous, adventurous, foolhardy, delightful, dangerous, non-conformist.' When reading Viidikas's work I always have the sense that she is holding nothing essential back, that her life and her art are inseparable, that here is a writer driven by the need to write and is ultimately always positive. In one of my favourite poems ‘Mamallapuram (Tamil Nadu)' she writes: ‘The ancient calendar revolves its execution – there's no moment too small for the birth of another dream.' It's a line that has become something of a personal ‘seize the day' mantra.

AA: Looking at her first published poem ‘At East Balmain', published when she was nineteen, it seems to me she possessed the desire to look for the extraordinary within the ordinary. She writes: ‘This day will be submerged in a thousand other days / yet I know distinctly I felt the glance of a figure / in a singlet, rolling cigarettes as his barge went / up stream.' Could you speak to this desire for distinction, attention and intensity of feeling in Viidikas's work?

BS: Yes, I'm glad you have focused my attention on that poem. It's finely observed, hinting at the connections between people that so come to motivate her later writing. It would be hard to imagine a piece of Vicki's writing that in some way didn't bore down into a feeling or emotional centre.

Elsewhere in the poem ‘a hermit dog lives here, in a burnt-out boiler turning / orange. He stays inside all day – I‘ve seen his eyes / glint in the dark, he is huge and black and solemn.' It's a poem full of understated feeling, of now and forever, of ‘the feeling of walking across the water, / without moving a muscle.' The poem's final emphasis on the fragility of life, the description of a dead rat ‘grey and stiff, with his tiny mouth open, arms stretched about his head' is counterpointed with an earlier description of the eternal nature of the river, ‘clear water washing million-year old stones.'

It did not surprise me that the word ‘eternity' was mentioned so much in her unpublished writing. In an interview with Hazell de Berg Vicki said ‘writing for me is process of drawing the spirit out of myself … It is to me in its simplest sense a religious feeling that I want to pursue and discover in myself.' Vicki was someone who saw and felt things acutely and possessed the gift to write those feelings and experiences into words.

As her friend Kerry Leves writes in the introduction to New and Rediscovered, ‘Vicki lived a full life; she embraced experience, even flung herself into or out of experiences, but not in search of something to write about. Her living like her writing was guided by a commitment to going against the grain.' The intensity of feeling in Vicki's work comes from its lived and often unconventional truth, a lifetime of seeking answers to the big questions that never ignored or sidelined those people the mainstream often saw as losers.

AA: Viidikas's first collection of poetry, Condition Red, was published by the University of Queensland Press in 1973. It's a remarkable debut, both in its confidence and courage to deal with deeply personal, sexual and unsettling themes (something that was perhaps considered controversial in the context of 1970s women's poetry) and also for its subtlety and sophistication. The poem ‘They Always Come', which I'd like to quote in its entirety, is a candid, gritty, and at the same time ironic and uncanny anticipation of her literary afterlife.

They Always Come

When they have taken away

the childish laughter and dog-eared books,

peeled off the last mush embrace,

given the girl

her lipsticks, hair rinses and pillsWhen they have poured back the drinks

as long as empty deserts,

returned the spurs to the one-night stands,

taken off the overcoat

and riddled her bed with songThey'll find

a mirror smothered in lips

a vacant room with stale cigar ash,

an unpaid bill for a Turkish masseur,

a woman's glove by a handsome typewriterThey'll see

charleston dresses of the mind

with their fringes running like blood,

a list of men's names

from childhood to eternity,

they'll dig the very fluff from the floorboards,

examine the stains on the manuscriptsWhich drug did she take?

Which pain did she prefer?

What does the lady offer

behind the words, behind the words?

Their criteria will be:

so long as she's dead we may

sabotage and rape

The possibly sardonic tone of the poem notwithstanding, what do you think Viidikas offers ‘behind the words' of her poems?

BS: I agree Condition Red has become a legendary classic because Viidikas wasn't afraid to write about previously taboo topics such as rape (‘Punishments and Cures'), drug use (‘Loaded Hearts') and sexuality. ‘They Always Come' seems to arise from an intuitive feeling about how the writer, the artist, the woman life's may be inappropriately used after her death.

In some ways it has come to be seen as a feminist poem and as presaging Vicki's own fate, though Viidikas was a complex person who, when asked by Sandra McGrath in Vogue if she considered her poetry feminist, answered, ‘I suppose it is – though I don't see it that way. Sometimes when I am writing a poem I am conscious of being a female, but not overall.'

My sense of Vicki's work is that in focusing on the body, the spirit and the emotions she was drawn to and understood the vulnerability that exists in us all, male and female. She writes sensitively and intelligently about men and women. In the very early story ‘Tambura in Darlinghust' there is an exquisite understanding of Gray's infatuation and ‘perfect loneliness', and elsewhere Viidikas taps into the vunerability of her male characters, the alcoholic in ‘Not Harry' or the burly slaughter man in ‘Letter to a Macho Man'.

The sardonic tone, the anger is often there but is counterpointed by a depth of understanding and an exploratory intent. As Kerry Leves has commented Vicki has the ability to make ‘a single image ramify into a nuanced conceptual arrangement.' Her poetry and prose often reverberate with a single image that opens out into layers of meaning. Behind the words the lady/writer/individual is ultimately alone, ‘the last permanent resident' (‘A View of the Map' from Wrappings), conflicted about which world to live in, always ultimately searching for Love. ‘Did You ever have this conflict / of which world to be in, / Queen, with cards stacked/creation on Your deck?' (‘Durga Devi' from India Ink)

AA: With the publication of books like Condition Red and others, as Stephen Oliver has written, Viidikas had ‘the Australian literary establishment of the late ‘60's and ‘70s […] open their arms to her – success was hers for the taking.' But it seems to me she preferred to live a full, eventful life instead of pursuing literary glory. Could you talk a little bit about that, about Viidikas's travels in particular, and about how experiences such as living in India shaped her writing, culminating in her last published book, India Ink (1984)?

BS: In 1972 Vicki received a young writers' grant from the Commonwealth Literary Fund and went overseas for a year – to England, India and Asia. India made a deep impression on her – and in spite of the caste system she could see that the different, the outcasts of society were allowed to be themselves.

Cities bared their souls and a richness of life and spirit was not tied to material wealth. ‘Listen … I learn more here in one hour than in one year of being alive in Australia, and there is no hot water on tap' (‘Rich in Madras'). I remember Vicki's mother, Betty Kunig, telling me how much Vicki wanted to take her to see India, to show it off to her. As journeys there grew longer and personal relationships developed it must have increasingly felt like home to her.

Certainly India, despite its frustrations, became her spiritual home and a major character in her writing. Gray, the character in the story ‘Tambura in Darlinghurst' fascinates Felina because he lives as an Indian: ‘He lived and breathed as an Indian.' India figures in Vicki's writing from very early on and India Ink is arguably the best Australian writing about the subcontinent. India is never romanticised, yet the poet captures its spirit and contradictions.

Viidikas kept an extensive diary of her time there and as well as India Ink worked on her novel Kali and the Dung Beetle, almost published by McPhee Gribble at the time. Hopefully a full version of the novel will be published in the future. Thanks to Vicki's mother, Betty Kunig, and sister, Ingrid Lisners, an excerpt is in New and Rediscovered. A number of illustrations that Vicki did in India also appear in the new book.

The volume of Vicki's writing and the seriousness with which she regarded it is indicative of a writer who deserved to be published more in her later years. Her exploratory subjective tone and voice seemed to lend itself best to short fiction and a form of prose poetry that was perhaps less fashionable in the nineties, while her novel Kali and the Dung Beetle always seemed to just miss out on appearing in print. Experience and art were, for Vicki, one and the same thing. And while I suspect that it was a disappointment for her that her later work was less published the rewards and daily discoveries that her writing revealed to her were significant.

AA: You've included ‘Lust', perhaps the last poem Viidikas wrote. It is a haunting meditation on a lifetime of rejecting social norms and conservative mores. She concludes the poem by writing: ‘I would rather live on flowers, / and a diet of grace. / I may be the last spinster.' Can you talk about the legacy of this exceptional poet?

BS: Vicki's question in that poem ‘Who will bring back the beauty, / the ecstasy, the mystery / of creation?' mirrors her preoccupations with writing the body and the spirit. In ‘Durga Devi' in India Ink she writes ‘why am I never right/to come to whole love/in this world of flesh and men.'

In a way ‘Lust' posits a rather unfashionable view that seems brilliantly Vicki but is also deeply felt. I am positive that Vicki's rich and undervalued legacy of fiction writing and poetry that so beautifully explores and questions relationships and spiritual meaning will speak to a new generation of readers. In her life the rich, glamorous ‘perfect stranger' driving her across the Harbour Bridge, Hendrix playing on the stereo (‘The Snowman in the Dutch Masterpiece' from Wrappings), became an ‘emptiness', but one perhaps she ultimately craved because it allowed her to be true to her art and herself.

‘I wanted to write a poem of the silence of the desert. I wanted to leave the body and enter the heart of the mountain … Right now I am mutating into a wordless book – when I‘ve done writing I‘ll send it to you. This is not a death wish, a severed tongue or a headless fool – I'm swearing with illuminated ink, to get it right, right.' (‘Illuminated Ink')

‘So I tied the red string and it/ fluttered like blood against pure white stone. In that moment I believed in eternity forever.' (‘Tomb and String' from India Ink)