Poet, raconteur and cryptogrammer Arjen Duinker may be one of the few writers living in the Dutch city of Delft. Cordite editor David Prater caught up with him recently for a wide-ranging discussion about books, writing, festivals, travelling and Australian Customs sniffer dogs …

Poet, raconteur and cryptogrammer Arjen Duinker may be one of the few writers living in the Dutch city of Delft. Cordite editor David Prater caught up with him recently for a wide-ranging discussion about books, writing, festivals, travelling and Australian Customs sniffer dogs …

DP: Arjen, the first question I wanted to ask you is – obviously, I'm interviewing you today as a representative of an Australian magazine, so for our readers who maybe have no idea what it is to be a poet in Delft, I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about your connection to the place where you live?

AD: Well, I was born here in Delft. Delft is a small town let's say between The Hague and Rotterdam; Amsterdam's just a train's hour away from here … so it's the west of the country. I was born here, I was raised here, my school was here – okay, I studied a bit of psychology and philosophy in Amsterdam and Groningen, but I came back and I have lived here ever since.

Can you expand on that a bit – what does Delft mean to you as a poet?

Well, I don't know if it means a lot to me as a poet. It's where I want to live. As long as I live here in this country, I want to live here. I could not – no, I wouldn't want to live anywhere else in this country. This is the place I like. I hate it as well, of course, that's how it is.

But I love it, I feel comfortable, it's a quiet, well, let's say smallish town, not even one hundred thousand inhabitants … so I know a lot of people, I know the streets, I can go on, ah, shouting at people, waving [makes strange noises] you know, like that – it makes life very easy for me, and a good thing is that I'm in no way part of any scene. You know, let's say most poets live in the bigger cities like Amsterdam, and Rotterdam as well, also The Hague, Utrecht – not me. So I don't play any part in any scene, any quarrel, any – you know, I don't see poets when I go to a bar, I don't talk poetry, hardly ever talk poetry; that's lovely, really, fantastic.

Which I guess leads me onto my next question, in that perhaps in your position as a person living and writing in a small town, separated, as you say, from the so-called scene, you're in a better position to describe for people who've never been here what that scene is?

I don't know, it's very difficult. You know.

How does it appear to you?

It doesn't appear to me. Look, another thing is I don't read newspapers. So, if anything is happening, I may hear about it a month later, or a year later. There are a lot of things possibly happening that I don't have any knowledge of.

Yep. Okay.

So, I don't know. Here – there's one other poet here, living here.

Okay. Right.

There are a lot of poets pretending to be, wanting to be a poet, but they're not. Well, that's life. No problem. That's how it is. I know there's more activity in the bigger cities, you've got readings, you've got clubs, organising evenings and soirees, and smaller or bigger festivals … every now and again I'm invited, so I, well, I go there, but I love to come back as well, as soon as possible, please.

[Laughter]

I really cannot tell you about how it works – I don't play any part there, in those environments.

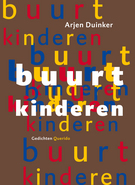

But you are of course a poet, and Querido has just released your eleventh book of poems, Buurtkinderen ('Neighbourhood Kids'). In what year was your first book published?

But you are of course a poet, and Querido has just released your eleventh book of poems, Buurtkinderen ('Neighbourhood Kids'). In what year was your first book published?

Rode Oever ('Red Shore') was published in 1988.

Can you tell me a bit about how that book came into being?

The first one was, ah, well, let's say a result of eight years trying to write poetry and convincing myself that it might be poetry that I was writing, you know. In the end, I thought – after a few years I thought my god, this could be poetry, eventually. Well, who knows? You know, and this goes on and on and on, and I started really liking it and, well, at least maybe getting some experience in writing.

Of course there's also the element of comparison, when you read stuff written by others and you read your own stuff, you can reach this point of saying very happily, facing yourself: my god, this is good, this is actually very, very good.

[More laughter]

That's a good feeling, you know! No, it's encouraging, you know. It took me about six or seven years to write that one. Because I'd never liked poetry at all. It was a strange decision to head in this direction, you know.

Before you started writing poetry, then, what sorts of things did you write? I know that you have done work as a crossword puzzle writer. Can you tell me about that?

Yeah, yeah, I made them, that's right. Of course, I studied psychology and philosophy but didn't finish them, and I also did sports columns because, well, sports were my life, more or less, far more than writing. I liked to read, though – when I was in school I loved reading, I read a lot then, I think. I don't read a lot any more.

Is that right?

No, not at all, no. But it started, I think, by writing letters to friends here when I was in the north, studying, the north of this country – it's extremely small when compared to Australia, it's ridiculous, it's three hours by train but it's, my god, an eternity for me, you know. So that's why I started writing letters to people; let's say my father, my mother, friends. This developed slowly, slowly into writing different things, that may be, might be, someday, poetry.

In what sense do you feel as if your books are published for a specific audience? I guess, you know, when you write a sports column, you have a certain sense that the people you're writing for have an interest in exactly the same thing – the same subject area, you know. Do you write for a certain audience now, in your poetry?

No, not at all. I probably write just for myself.

Yeah?

As long as I like it and I can grin and laugh and curse a lot, you know, I think I'm on the right track. That's about it. And, of course, there's nothing wrong with being patted on your shoulder or flattered or whatever, it's nice now and then, but it's unimportant in the end, to me. I know, in a way – it's not a very conscious thing – but I know what I'm doing and I know why I think this is good poetry. That's more or less what keeps me going. It's not about a public, it's not for or to a public or an audience at all, not a special one, no.

[audio:http://cordite.org.au/audio/duinker_schippers.mp3]Arjen Duinker reads his poem 'K.Schippers, moet je horen!'

[you must have javascript enabled in your browser]

Click here to view a video collaboration between Arjen Duinker and Paulien Oltheten, entitled 'Vogels Antwoorden Niet'.

So I guess in terms of performing your work – you've performed your work at various festivals, around the world and I know that you've seen some parts of the world I'd very much like to see myself –

[Laughs]

– and you've also recently performed at the Rotterdam International Poetry Festival. In the context of what you just said, how do you approach a performance or a reading of your work?

Well, I hardly approach. I'm there, of course, I take a few books with me. An important thing is you've got to have translations to go places, and the amount of translation is limited, so your choice is a limited choice. My choice is sometimes, most of the time, a limited choice – not here in the Netherlands, of course, but elsewhere. And then it's just, well, I don't want to just please the public, I know there are poems people really love. Okay, I may read two or three of those, but I also want to read a few other poems, which maybe the audience wouldn't like, or wouldn't immediately like.

In that sense do you see performance as a way to take a risk, to experiment?

In a way, yeah, I think I do. It's, well, it's not such a big deal, but yes, you could say that. You know – but perhaps Australian people do not know – that I have written quite a lot of poems for two voices, reading them with a good friend of mine. We always read them in a different way. We don't rehearse. And it's the same with the poems I read on my own. I'm not in my room, I'm not here in my apartment rehearsing and rehearsing, let alone looking in the mirror – how do I look, how is my face, how is my mouth? No, no. Are my eyes okay? No, no I don't do that. Sometimes, in the train, I look up a few things; think 'Jesus, did I write that? God, let's read it! God, when was that?!'

It must be very convenient to have so many surprises up your sleeve when you need them.

True.

As we've just been discussing –

No, one more thing: in a way, it's about keeping some kind of freshness, you know. I don't want to sound, at least to myself, the same all the time – the same for writing. I've got to go on, move on. Of course, I will always be my own poet, I mean, writing my poetry, but I've got to have this feeling of going to the left or to the right, or backwards – who cares! – but doing something.

There seems to be a sense within your poetry itself, a sense of travelling that is perhaps not quite the same as the physical act of travelling. In some of the more recent poems that you've written, which will be performed at the Rotterdam Festival, there's a sense of being on the way to somewhere, or of travelling or experiencing another place. But it seems to me that there's a very strange – well, not strange – but a tension between some of the things you don't like about travelling around the world –

[Laughter]

– and the things that make travelling so good, you know? The moments where you think, 'oh, that's a poem', you know? Do you know what I mean?

No, not really, I –

Okay –

Not really, no. The thing is, I like to be here, at home, and I like to go places, but not all the time. I feel very, very comfortable here, in my place. Now and then, okay, a trip to wherever, that's good. But no, no – I really like to be here, I do my writings here, I hardly ever write when I'm travelling. Of course, one sees things, one hears new things, okay – but that doesn't make me write poetry.

Okay, next. I guess what our readers are most interested in are your impressions of our wonderful, wide brown land, Australia –

[More laughter]

– which you visited on at least one occasion.

Yes, just the once. It was just Melbourne, I didn't see any of the typically Australian animals – maybe one bird? No, I saw just a bit of Melbourne. I did a lot of readings, radio, interviews, a workshop, which was quite busy, and full. And it was lovely to be there. Later I wrote a poem called 'Melbourne Is the Best Restaurant In the Whole Wide World'. Yes, I loved it, the food, and I so much enjoyed the people I met. It was a fantastic trip. And I really, really loved being checked, you know, all over, coming into Australia, because a dog had reacted –

Oh-

I didn't notice the dog, but the dog noticed me!

[Laughter]

So it took me at least two hours to get out of the airport. After such a long journey, oh god, I was tired! But I kept my politeness, I think. I tried to. They said, 'What brought you here, where are you staying, sir', all this sir, you know, like in the States, sir, sir. In the end I seem to have convinced them I was okay-ish.

It's very reassuring that our customs services are doing such a good job in letting the good poets through, yeah. Now, another project you've been involved in that has also involved a number of other poets has been a translation of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass.

It was a project organized by two friends of mine. They asked, oh, let's say twenty four Dutch poets to translate a part of Leaves of Grass. So the book was divided into that many parts. It was published four or five years ago. And, well, of course, all of these translations were very different, some literal, some very, very freely done. It made for an interesting book, I think.

I loved doing my part, I really liked it; my god, lovely, lovely! Yeah.

What did you like about it?

I don't know, in a way it was so … it was quite easy for me to translate Whitman into Dutch. In a strange way it was close to my own poetry, now and then. I can't explain this very precisely, but it's easy going, I liked it – and that was the main thing: I really, really liked it. Also, when the book was published, the whole of the book was read at the Rotterdam Festival, by all these poets. How much time did it take? Six hours or something like that. But it was lovely to read, as well. Stunning. It may be tragic, it may be hm-hm-hm, it may be democratic, I don't know, but it's also very funny poetry to me.

That's an excellent project to be involved in. If you had to recommend a Dutch writer or a Dutch text or a book that non-Dutch people could read, that for you sums up the kind of writing style that you admire …

Ah, that's difficult. I don't really like Dutch poetry at all.

Right.

No, to be honest, no. I understand that there are in this small country six hundred thousand people writing poetry … well, okay, you've got this figure of one hundred or one hundred and fifty, you know, poets publishing quite frequently, with good publishing houses. I think, in my opinion, there's three or four really good poets, that's about it. The rest is very, very average – or even worse.

Okay, yeah.

But like anywhere, they've got a big mouth, they talk about one another, they write about one another, they turn into things far bigger than they are. Happens all the time, of course. Nothing new. The one poet I really like, and have liked, is someone who doesn't really like poetry anymore. But I don't know, I've been influenced by some of the poetry that I've read, like Chinese poetry, American poetry, Latin American poetry, some Italian stuff, poetry from Iran, from Africa, things like that. No English poetry, funnily enough.

Is that right? I was waiting for you to say that!

And no German poetry, either. No, no. I liked a few Russian poets, a few from Poland, from Croatia, Turkey as well, very good poets. But there's no German poet in my top twenty list. And no English one. No, really, honest. I don't want to offend.

Not at all! I'm not offended at all …

[Laughter]

So one of the last questions I wanted to ask you is, what's on the go for you now? Do you write all the time, or are you finished for the moment?

Well, for this moment, yes – I just finished the book that's out now. It's over 200 pages long. My god, I'm fed up with myself for at least a few weeks, a month! But I'm doing collaborations, writing with a Slovenian poet, another one with a Brazilian poet. And then I want to write four plays, and I'm planning to write a script for a movie. And, of course, now and then despite myself I will write a poem, a simple [laughs]…

Ditty?

Yes, something like that – it's inevitable. I think that's about it.

Finally, in terms of the collaborations and working with poets from different countries, I'm assuming that a lot of that collaboration is done via email?

Yeah, yeah, yeah… practically everything.

As someone who, like me – you know, I include myself in this description so that you don't feel like I'm making a sly comment – but as someone who can remember what life was like before the Internet –

[Laughter]

– do you think your use of the Internet has changed the way you write?

Hmm, maybe. I find it very convenient, to be honest. No, I don't think I ever – I'm not good at thinking. No, I never think of the past in that way, I'm not – a past man. I find it very easy, and I like to combine the two things, you know, simply be there at my small table, trying to write a bit of poetry, and at the same time sending mail, or answering mail, and it's a funny way – like Australia, what's the time difference, nine or ten hours? Depends of course on where you are, but I'm doing a project with a poet from New Zealand, the difference is eleven hours, I think. So it's funny, when I am 'fit' and healthy and raring to go, he's on his back, or he's drunk. No no, the funny thing is he doesn't drink. I do. Sometimes I send an email to the States, or to Latin America, and I realise they're still asleep-of course, I've got to wait! Shit!

I may wake them up!

Ha ha! Yeah!

You've got mail!

Ha ha, yeah. But I like the medium, you know. It's silent. I'm not someone who makes many phone calls. Of course, I answer them. But I like this silent medium – go anywhere, anytime, even without being noticed, okay, no problem. It's good.

And I guess, ah, my very last question – how comfortable do you feel about your work being available online? Or knowing that there is a Wikipedia page about you?

Yeah, I saw that. I wonder – I think I can find out who made it.

Maybe.

It's okay. I never read my own stuff on the Internet. I'm not looking at my Wikipedia page, I know more or less who I am. Or not. Both are okay.