Among the most extreme, in the sense of horrific, writing places for poems bequeathed to us would be the conditions in which Ezra Pound produced The Pisan Cantos.

There is some speculation as to the exact number of those Cantos (or which versions) Pound wrote while incarcerated in 1945 by the American military in their Disciplinary Training Centre near Pisa, Italy. However, Pound certainly communicated via letter that almost all of the work was produced during his containment.

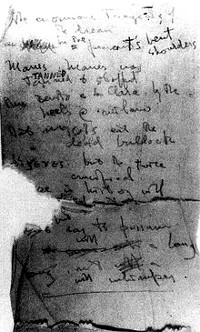

Pound was initially held outside in a reinforced cage, open to the elements, and is reputed to have slept on the ground. After three weeks – and in a state of mental and physical breakdown – the authorities gave him a cot and pup-tent in the medical compound. He had access to a typewriter, but only three texts were initially allowed to him – resulting in the in-turning into his own memory bank within the poems. The cage and Centre provided glimpses of the exterior world which are rooted throughout the poem. These progenitating vantages include the image which opens the work: ‘The enormous tragedy of the dream in the peasant’s/ bent shoulders’.

The fractured yet minutely and consciously controlled themes and language rhythms, and their recurrences – what the Times Literary Supplement called ‘a system of echoes’ – across the Pisan poems are powerfully linked to the place of their genesis: its madness-making, the content and metrical devices used by Pound to ‘ground’ or ‘peg’ the work.

Another series of famous poems whose making is linked to place is Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies, begun in 1912, a decade before their completion. He says he heard the first line as if from an external voice while walking along a cliff-top over the Adriatic Sea, near the Duino Castle, where he was staying on the invitation of a patron. The poems were completed in a Swiss chateau especially purchased for Rilke by yet another patron so the poet could concentrate again on his work – this after an interim decade of war and the poet’s traumatised ‘writing’ silence. (If place can be critical to the writing of certain poems, so too is such generous patronage, surely.)

Where dedicated writers write, when they write (their daily rhythms), how they seek and sustain inspiration and motivation … how they clock off the concentrated time given to deepening their craft … this is intensively chronicled. What is the passion, among both writers and readers, for knowing this stuff of a writer’s life? I think it’s a desire to clue in to the magic – in the arcane sense of the word – of the creative act, via the pragmatic rituals writers often use to do so.

We are interested in these histories, perhaps, because it educates us around certain clues that other writers can provide us in bolstering our own commitment to the structures we create in. Committing to a daily timetable, or a certain word-limit to be produced daily (in the case of prose), and choosing a particular place or set of places to write in or at: these are definitely commonalities among many esteemed writers. Of course, given the crankiness of the writing art, some writers will have no need of a regular place, routine or touch-stone.

The examples of Pound and Rilke demonstrate another aspect to the issue of place; the sense of labour which is compulsive and imperative – like that of a human birth – gestating the creation, then ‘birth’ of some poems. Many poets have experienced the power of creative force unleashed in this way. Where, exactly, a poet is writing them can become irrelevant: the poem will be written, regardless.

However, having a particular place that serves poets’ writing on an ongoing basis – and one which, for poets, assists them in being ‘ready’ to write poems – is important to many.

Numerous Australian and overseas poets have been interviewed at length about their poetry-writing habits, including place, in a long-term project currently under way by poets and academics Kevin Brophy and Paul Magee.

Alison Croggon told Magee on the subject of research:

‘I don’t intend as such, to write a poem. I wait for the poem to intend itself. I think most poets work that way. While I’m actually writing it, I usually have no idea what it will be and what shape it will have until I get to the end.’

Croggon considers it important to have your ways of ‘keeping fit’ or ‘supple’ in order to write poems, which involve, among other things for her, reading criticism and seeing art. ‘I think about language a lot, consciously as well as unconsciously’, she says. ‘A lot of the work I do is about keeping myself occupied and mentally alert.’ Croggon virtually always writes (and not just her poems) at her desk at home.

Alex Skovron, at times prompted to write poems when travelling, also described his study at home to Magee as ‘a great environment for writing. It’s peaceful, it’s well-lit and it’s quiet. I have an outlook on trees and an open space. In that sense, it’s conducive. Yes, it’s an excellent environment.’

In a recent exchange, Skovron told me that he has adapted this habit – over the past few years, ‘most of my first drafts (though not all) seem to have been written away from my study, in a variety of cafés and similar establishments. After bringing home a new draft, I type it up as a fresh poem-document and simultaneously commence the editing process – on-screen in the first instance, until I’ve produced a first typed draft, and then in subsequent sessions both at my study desk and at the computer.’

With Jan Owen, talking to Magee, the focus in her interview became what she called, ‘places in the mind’ … the ‘places’ she cultivated in order to write poems from.

So: poets write in locations where they can inhabit the inner ‘place’ – including the visual, external inspiration of a certain landscape or environment – that underpins their poetry.

Owen, in an email about this article, says that she ‘often finds ideas when wandering along the beach or in the local scrub (she lives in South Australia). I write early drafts longhand and usually revise and edit in the evening at my desk with classical music as a sort of white thought background. Occasionally, when I have a few hours to spare, I sit on the verandah of the old homestead type café at the little local airfield with a pen and blank pad: good coffee, bright little biplanes landing and taking off, 1930s’ mementos – another time and place that sparks the imagination.’

So polarities exist regarding distractions or noise. In Auden’s highly mastered and long meditation on his home, Weland’s Stithy, in ‘Thanksgiving for a Habitat’, the third section, ‘The Cave of Making (In Memoriam Louis MacNeice)’, is about his writing study. Earlier in the cycle, Auden reminds us – he did not own his own home until into his fifties, due to finances – that ‘what I dared not hope or fight for/ is, in my fifties, mine, a toft-and-croft’.

For W. H., absolute silence and freedom from any distraction was imperative:

For this and for all enclosures like it the archetype

is Weland’s Stithy, an antre

more private than a bedroom even, for neither lovers nor

maids are welcome, but without a

bedroom’s secrets: from the Olivetti’s Portable,

the dictionaries (the very

best money can buy), the heaps of paper, it is evident

what must go on. Devoid of

flowers and family photographs, all is subordinate

here to a function, designed to

discourage day-dreams—hence windows averted from plausible

vivenda but admitting a light one

could mend a watch by—and to sharpen hearing: reached by an

outside staircase, domestic

noises and odors, the vast background of natural

life are shut off. Here silence

is turned into objects.

Ted Hughes, in a Paris Review interview, talked about the multiplicity of places in which he had written, and how place definitely affected what was produced in it:

‘Hotel rooms are good. Railway compartments are good. I’ve had several huts of one sort or another. Ever since I began to write with a purpose I’ve been looking for the ideal place. I think most writers go through it … Didn’t Somerset Maugham also write facing a blank wall? Subtle distraction is the enemy—a big beautiful view, the tide going in and out. Of course, you think it oughtn’t to matter, and sometimes it doesn’t. Several of my favorite pieces in my book Crow I wrote traveling up and down Germany with a woman and small child—I just went on writing wherever we were. Enoch Powell claims that noise and bustle help him to concentrate. Then again, Goethe couldn’t write a line if there was another person anywhere in the same house, or so he said at some point. I’ve tried to test it on myself, and my feeling is that your sense of being concentrated can deceive you. Writing in what seems to be a happy concentrated way, in a room in your own house with books and everything necessary to your life around you, produces something noticeably different, I think, from writing in some empty silent place far away from all that … But for me successful writing has usually been a case of having found good conditions for real, effortless concentration.

Elsewhere, when asked to nominate the tools he required in order to write, Hughes’ answer was simple: ‘A pen.’

Poet Petra White tells me she will also often write her poems in a busy café environment. Lately, she has been writing them ‘on the go’ on her iPhone, she says.

But White also undertook a deliberate self-apprenticeship in poetry in the Domed Room at the State Library of Victoria (where I am, coincidentally, writing this piece today) in her early twenties. Here she read all the poetry in English that she desired to; and began to teach herself German in order to be able to read poets such as Rainer Maria Rilke in their original tongue. Other well-known writers who have worked in this room include Chris Wallace-Crabbe (as a ‘young poet’, in the 1950s), and novelists Peter Carey and Helen Garner – she wrote Monkey Grip here to escape the clatter of a communal household.

So, among so many places to choose to write, ‘the Dome’, as it is known colloquially, is a place that is creatively haunted and resonates with a remnant aura of a century of thoughtfulness. Particular public writing and research places have this sheen, bestowing upon a writer, poet or not, a place in which to establish habits away from home. A daily ‘seat’, of sorts, in which to write – which can also grow itself, I feel, into a kind of ‘portal’. You step into it, deliberately, and become absorbed by what you are there to do. (I am struck, after writing for a number of hours into the early evening, when the room’s antique-green desk lights glow dimly in the nocturnal cavernousness of this space, that only a handful of people remain of an earlier crowd. I had not noticed a single person leaving.)

What is also true: we grow to love a place where we have written what we wanted to write, which has housed us in what we might call … kindness.

We can return to Rilke on this point for the habitat (the Château Muzot in the Rhone Valley) in which he completed the ten Duino Elegies – and then the entire, extensive sonnet suite of Sonnets to Orpheus immediately afterwards (in three weeks of February 1922) – within what he described as ‘a hurricane of the spirit’, was one he described with tenderness. Rilke moved there with Baladine Klossowska, with whom he was in relationship. His thoughts about the chateau during this period of gargantuan writing are important, as noted in a letter to Klossowska: ‘what weighed me down and caused my anguish most is done … I am still trembling from it … and I went out to caress old Muzot, just now, in the moonlight.’ And in another letter at the time, to previous lover Lou Andrea-Salomé, he wrote that, ‘I went out and stroked the little Muzot, which protected it [the writing] and me and finally granted it, like a large old animal’.

These words were to inspire Auden’s own reference to Rilke’s composition of the Elegies, in Sonnet XIX from his 1936 21-sonnet cycle, ‘Sonnets from China’. I quote this work, along with the ‘Thanksgiving’ poem, from a collected edition of Auden’s titled W. H. Auden Collected Poems – The Centennial Edition. Here, from Auden:

Who for ten years of drought and silence waited, Until in Muzot all his being spoke, And everything was given once for all. Awed, grateful, tired, content to die, completed, He went out in the winter night to stroke That tower as one pets an animal.