A Handwritten Modern Classic by Finola MoorheadSpinifex Press, 2013

Be shot survive drink hemlock.

These three lines from The Seventh section of Finola Moorhead’s A Handwritten Modern Classic, first published in 1977 and re-issued March 2013 by Spinifex Press, close out a varied discussion by the author on the political nature of death, that Socrates’ death ‘was political’ (as underlined in the handwritten original), that Socrates was not a writer and that writers ‘need teachers like Socrates’. In the same section she argues that artists often use ‘Another’s pain … for the success of expression’. ‘Art as comfort’, Moorhead follows on, ‘ — strange concept. / Such assumptions aren’t questioned often enough.’

In an example of the dizzying range of subjects trawled by the book, The Seventh also includes a meditation on her lesbian relationship and its powerlessness to escape the poly-political. She and her partner move to the country to escape the broil of anti-freeway protests in which she had been involved: ‘A quiet, bushy place with tall bush & clean icy water’ and where the two could ‘eat fresh fruit & relax. Listen to the birds’. Instead of tranquility,

‘Suddenly there was horror … Many different camps of men: guns, trail bikes, cans, cans, stubbies & bottles. Boys sold things to rape the bush with. Come to piss & shoot at anything that moves. What could two lesbians do? … That we could not escape is a reflection on our romance.’

The cross-genre quality of Moorhead’s ‘classic’ is one of the reasons the book remains relevant. Part-memoir and part-manifesto, it’s a long, fragmentary love-letter, an on-her-record account of stoushes with peers, a radical-lesbian-feminist tract:

‘Oh shit. I reject the Institution of the Family. I must … Families all start wrongly with heterosexual monogamy & the children suffer all sorts of resultant tensions arising from that.’

It’s also an incendiary incantation whose language, at times, incorporates the swell and fall, the self-impelled syntax, the short/long lines, the sudden breakages, of poetry. The first three lines quoted qualify as an English-adapted haiku.

Spinifex publisher Susan Hawthorne says she decided to re-issue Moorhead’s ‘unknown treasure’ (originally published by Post Neo in 1982 and out-of-print for over a decade) because of its ‘clear portrait of the literary scene in Melbourne during the late 1970s’ in what was ‘a very exciting period of change, experimentation, political protest and all that comes through in the book and in her aphorisms’.

But when reading the new edition – published in the handwriting of Moorhead, as was the case with the original edition – I found the localised, literary and political historic aspect may not be as great a hook for readers who were not of the first edition’s generation. I’m lured instead by its enduring vitality – the mark of a classic. Moorhead dips her courageous, argumentative stances in the acid of impending postmodernity’s wrestling with what can be said to be real, true. In that, the book’s double-act constant of porousness and intellectual wilfulness keeps it and its questioning lines alive.

Note, however, that Moorhead is conclusively against writers being indulgent. As she writes in The Ninth section:

‘While there is pain, there is choice, but one can’t rush around all the time in hysterics, as if our coats were on fire. We must refuse to.’

‘The only reasonable escape is the effort. / We must confront the corrosion in ourselves.

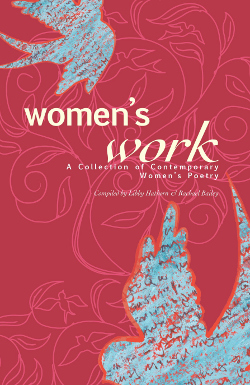

Women’s Work: A Collection of Contemporary Women’s PoetryLibby Hathorn and Rachael Bailey. Pax Press, 2013

The best poems in Women’s Work – A Collection of Contemporary Women’s Poetry (compiled by Libby Hathorn & Rachael Bailey, Pax Press, 2013), compiled to mark this year’s International Women’s Day and launched on that 8 March day at the University of NSW – have the corrosive, enquiring and discomfiting power of ‘good art’ (read, writing) as debated by Moorhead in her book. Such outstanding poems include contributions by Gig Ryan, Sarah Day, Tricia Dearborn, Rachael Mead, Kathryn Lomer, Felicity Plunkett, Susan Hampton, Brenda Saunders, Lucy Dougan and Louise Wakeling.

Mead sharp-keels the typical, lamenting description (ad infinitum) of housework’s overload in a poem that both disorients and agitates to the madness of the domestic’s repetitive strain. In five triplet stanzas, the poem rolls out:

fold the plates away / iron the bench tops / measure the clothes on the line // shave the carpets / exercise the rubbish / escort the dog off the premises … peel the bathroom / steal from the hens / paint images of the self on all shiny surfaces //

before closing with what resonates like a machine-gun knock-on to Moorhead’s ‘drink hemlock’ (having read the books concurrently):

repeat / repeat / repeat

In Virginia Woolf’s landmark essay, ‘Professions for Women’ (1931), the author discusses the necessity of killing whom she calls ‘the Angel in the House’ – that lovely, sympathetic phantom who ‘was intensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg … Above all – I need not say it – she was pure.’

Woolf kills her. ‘My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self-defence.’

This act of murder is related to the uncompromised writer present in the stronger poems of the Women’s Work collection – the writer now engaged instead in the ‘difficult arts’ of the ‘work’ of writing. In this way, this poetry collection is a double-take: on women’s ‘work’ and related matters, but in its best sense, it is also about women at work in their writing, implicitly. These poems include Gig Ryan’s ‘Fake Work’, on the treacherous compromise, and mortal consequences, of desolate employment; Sarah Day’s two excellent ‘Exits’ poems, describing nursing work; and Kathryn Lomer’s ‘Sorrow of the Women’, describing the practice by Chinese women of using their own, encoded script in secret letters (tattooed on rice paper or via embroidery) to female relatives or friends, to describe their terrible woes, a script banned by the State in the 1950s.

In these, there is no sentimental or genteel rumination about ‘women’s work’, associated work experiences and life-experiences – which can be the case with some runs of weaker poems in Women’s Work. Instead, the achievement is in how the unflinching, poetic exploration of these experiences transcends gender – when it is relevant to do so – or when it is equally necessary to deepen our connection to the female humanity of the subject.

Interestingly, in both Ryan’s and Day’s examples, the poems could have been identified as having been written by men, and about men. I like this gender-neutrality. Among the most moving poems in the collection are Brenda Saunders’ ‘Innargang’, on the horrific experience of a grandmother removed from tribal land to be in service … ‘nights with white men smelling of grog./ Black arms cradle a new fear / beneath her swelling apron’ … and Susan Hampton’s ‘Lily Bailey and the English Lesson’, quoted here in full:

the oblique edge of fear entering

her face

over and over as she fails one thing

after another

both her hands shake, even

the one holding the page flat

at 14 she wants

to be 4 and start again

before she was put in the Emily Penshurst Home

before her mother broke down and gave her away

to another suburb

before her father beat blue patterns on their

solid white arms

before her father drank

Lily wants to be re-conceived

but she cannot name the wanting

Lily shakes

as she tries to write NOUNS and the date.

Forgetting enough to make survival possible,

she can’t remember nouns, either the spelling,

or what it might mean

In 1909, International Women’s Day began as International Working Women’s Day, a radical initiative by the Socialist Party of America, to commemorate the struggles and achievements of working and disadvantaged women. Hampton’s and Saunders’ poems reminds us of that original legacy and of Moorhead’s power to espouse an art that is not a ‘comfort’. Women’s Work collects many worthy poems to meet the injunction Moorhead proffers in The Handwritten Modern Classic – and eye to eye. It’s a tough gaze.