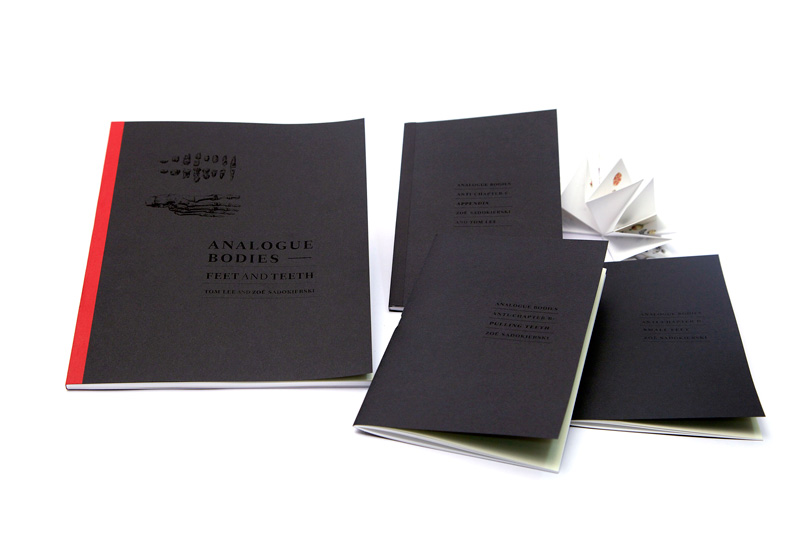

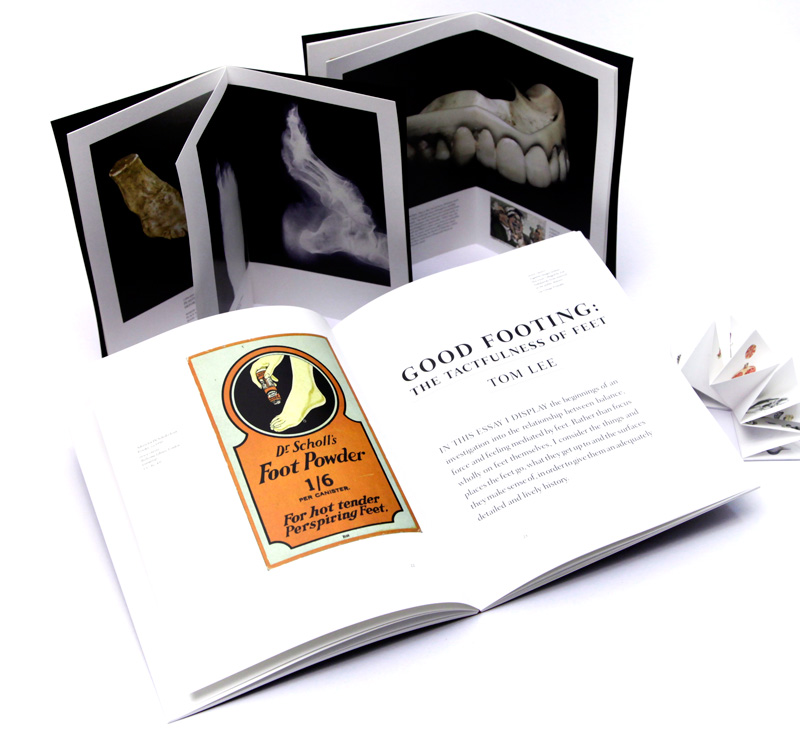

Analogue Bodies is a collection of essays by Tom Lee, materialised as set of illustrated books by Zoë Sadokierski. The project looks at different parts of, and events within, the human body and historical ways of depicting and making sense of them. It aims to humour and, on its day, to educate. It was presented as part of the recent Emerging Writers’ Festival 2014 at the Wheeler Centre in Melbourne.

Here, Tom Lee and Zoë Sadokierski discuss their collaboration, Lee’s motivation to write about feet and teeth, and Sadokierski’s motivation to turn those essays into book object, to get them into the hands of likely readers.

Tom Lee: I recently watched a brilliant BBC documentary hosted by Simon Schaffer on the history of clocks and automata. Schaffer is a historian of science who teaches at Cambridge University. The documentary is distinguished by his detailed and wide-ranging scholarly knowledge and the delight and sense of drama he brings to the presentation. His diction has a forceful, yet eccentric rhythm, which is accentuated by the shape his face gives to the words and his incredible, what I consider stereotypically British, teeth.

The subject matter too is often astounding. Automata are moving, mechanical devices that imitate living beings. Some of the specimens from the 17th and 18th centuries are no less impressive in their intricacy than the inside of a laptop, and they are without doubt more spectacular in terms of their appearance. As Schaffer notes at one point, some of these mechanical beings share in the ancestral matrix of ideas and practices which spawned computing and moving image technologies, now pervasive in modern settlements. So in a sense, the on screen Schaffer, the Schaffer speaking to me through the laptop screen, is conducting an analysis of his of own DNA. He too is a mechanical, moving image.

Schaffer’s meditations on the artisanal and artistic genius of these automata prompted me to reflect on my own vocation, in particular this project, the shape of which I was only beginning to intimate. Spending good portions of the day trying to come up with clever and surprising ways to describe parts of the body, one finds oneself asking questions of their activity: what was I up to, writing unprompted essays on feelings of the feet or mythological understandings of tooth structure?

Which historical precedents could I nominate as touchstones or accomplices? Schaffer’s documentary and his automata makers seemed to me an ideal reference point to weave into my own program. I was no artisan, engineer, jeweller or artist: I was a writer, more specifically, someone writing essays with a commitment to the idea that poetic thinking is essential in providing things with adequate and lively histories.

The similarity between my activity and the activity of the automata makers lay in our common effort to imitate the human form through the use of technology. Theirs: resistant things like woods and metals. Mine: the softer medium of writing, and its associated forms of display: the screen and the page. The word poetry comes from the Greek word ‘poiesis,’ which means, ‘to make.’ The distinction between those who make with materials and those who make with writing has a blurry edge.

The way I like to think of it, I am engaged in the task of producing an expressive and convincing account of the human form, just like the builders of automata. To me such an account seems contingent on seeing the human body as bound up with a continuously growing series of things, or, to use a word of the times, as part of an ecology: mud, fruit, tin cans, aliens, x-rays, soft toys and glass.

Although the sentences of my enterprise lack moving parts, they were written with a strict adherence to the notion that I must capture the movement of thought. That evasive, difficult to teach quality of rhythm which makes it seem as though the written word is chatting away to the reader.

Something else in this writing enterprise seems in communion with Schaffer’s toy tinkerers: it is about the body in parts. At one point in the documentary, Schaffer notes that the artisan clockmakers of Europe were a specialised and distributed workforce, with some city streets being defined by the different clock parts they produced: springs, drives, tiny gears and so on. As a friend who also watched the documentary helpfully pointed out: ‘This is what you are doing too. In order to build and then animate the body through writing you are first breaking up its constituents and dealing with them in isolation.’

This series is an examination of the human body piece by piece, with each part spun through sequences of sentences and paragraphs.