SYDNEY. It’s aqueous. Shiny. Shifty. Stupid. Braggart. Gorgeous beyond measure. Cruel. Exorbitant. A geist that puts hooks in where you do your hardest wanting.

The town’s biggest fools are those who come from elsewhere and fall in love with it when they’re young. As a rule, these fools fall hard, beyond reason and recovery. I know because I fell that way. As you do when you’re twenty. All fresh and juiced up, you don’t worry about the decrepit infrastructure or the administrative corruption. Addled in every one of your glutted senses, you can’t see or care how the town gets everyday filleted in a deal serving a municipal cabal of legislators, police, realtors and gaming & liquor factotums. To use the local parlance, they don’t really like each other, but they’re all well and truly up each other.

I recall attending a lecture sometime in the 1990s, given by the screenwriter Ian David, who expressed admiration at how easily just about any scrum of rogues can skim their comfy percentages in Queensland so long as they suck up to the right two or three people. Queensland’s where I was born and raised, so I felt a little puff of pride. But then came David’s main point: Queensland is smalltime … what really makes you gape in awe is the system in Sydney. ‘Right from day one, January 26 1788’, he explained, ‘a crooked network of petty overlords simply seized the means of production! Police, pubs, property-pushers and pollies. No skimming. Direct, vertically integrated profit!’ And it’s never been dismantled, this 200-year regime.

When you first come to Sydney, the corruption seems rakish. What fun, this coalition of bandits. A few years stutter by till you wise up to the fact that, despite how visionary it was at the start, nowadays the graft is asinine, smug and lazy, gluttonous, ruthless and unimaginative, and its beneficiaries are mostly just a crass bunch of dumb pimps. (Don’t get me started.)

As the decades roll by, some lovelorn saps might try to get the hell out of town. They might even succeed. But don’t forget, they’ve already been whipped by that first love, so if they happen to backslide – – say they return for just a day and the town vamps one of its come-hither guises and gives off all that sparkle and wattle-nectar – – then every pledge and resolution has to go to mist.

Greg Brown, the great American songwriter, once lamented about a whole ‘nother stupid passion: ‘She says to me ‘come hither’ but when I get to hither she’s yon.’ He could be singing about the town. Think of Sydney as a woman, think of Sydney as a man – – it makes no difference with equal-opportunity duplicity. As an old friend once observed: regardless of what it is coming over the horizon, everyone here tries to make dough with it, once they’re done trying to make out with it.

In a long line of writers and artists who have composed heartsore love-letters to Sydney, I have been working for two decades with a collection of crime-scene photographs that were generated by the Metropolitan arm of the NSW Police between 1945 and 1960. A dozen different creations have loomed from the archive. The project I’ll sample for you here is a weekly minimalist blog called ‘Accident Music’. Every Sunday, I make a new post – – just a picture and a few words that chase a local mood.

But first, to catch and give context to the sly pleasures that always throng the town, here are some of my favourite writers from the thousands who have lolled in Sydney’s thrall and have known its amber strangeness before I came and fell.

From January 1788 till December 1791, William Dawes was a marine in the First Fleet colonising Sydney Cove. He was twenty-six years old when he composed his handwritten ‘Language Notebooks’. On ninety neat pages, Dawes recorded phrases from months of intimate exchanges that he enjoyed with a young Indigenous woman called Patyegarang. There’s a warm and hedonistic sense in the notebooks, in Dawes’ haiku-short records of scenes that play out at dappled harbour-beaches and sandstony dalliance spots:

Matingarabangun – – We shall sleep separate.

Mekoarsmadyeminga – – You winked at me.

Putuwa

wiaga– – To warm one’s hand by the fire &

then to gently squeeze the fingers of another person.Wirribara – – Shut the door.

Wanadyiminga? – – Will you not have me?

Gon. Mama Kaowi ngalia bogia – – My friend, come let

us (two) go and bathe.Nyimu ng candle, Mr D – – Put out the candle, Mr D.

D: Minyin bail nandyimi? – – Why don’t you sleep?

P: Kandulin – – Because of the candle.

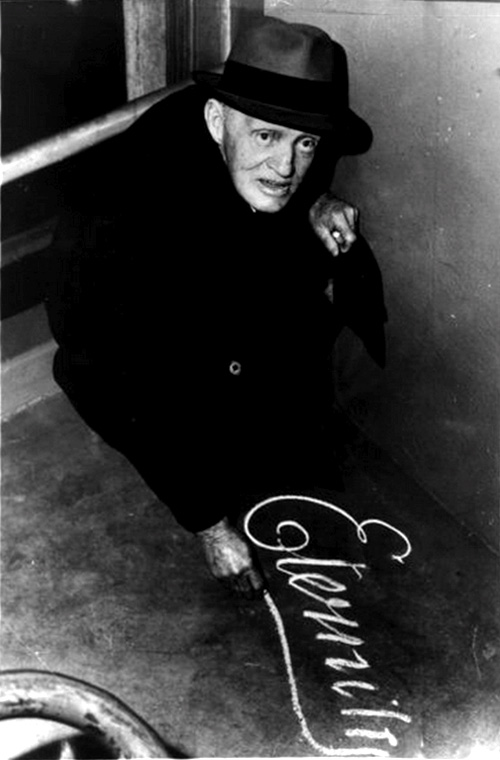

From early 1930s till the mid-1960s, Arthur Stace was the ‘Eternity’ man. Sometime in the 1930s this reformed alcoholic began his great writing project. His early versions exhorted: ‘Obey God’ and ‘God or Sin’. Written on the ground all over town. But within a year he settled on the single word that he would write more than 500,000 times – – ‘Eternity’ – – mostly on the cement pavements in the horseshoe of suburbs from Annandale around to Kings Cross, but sometimes along train and tram lines all the way out to Parramatta.

There’s no way to improve Stace’s tender, reiterant poem. With decades of practice he refined it exquisitely. There’s glory but also doom limning the delicacy in his copperplate text, so assiduous, so portentous, so pious and devotional.

See the plump avuncular ‘E’, see the ganged worker-bee letters saying the phonetic commandment ‘ernit’ in the middle, see the generous embrace of the recursive tail in the ‘y’, and see how the last thing he did with every inscription was to make a crucifix of the second ‘t’. Having planted that cross to finish his prayer-poem, he would make ready to start it again.

Half a million times, he wrote it, using a particular brand of crayon that he chose after some years of research. Better than chalk, the crayon, because it stayed legible for several weeks on the ground but always wasted to nothing as time stretched over months.

Each inscription would get weathered away, not wiped away. The people of the town found and cosseted his utterances as if they were rare ferns or burgeons of delicate moss. So striking was Stace’s mark, so ephemeral its form. Half a million times he failed and also succeeded to make his message eternal.

‘There are in our existence spots of time,’ wrote William Wordsworth. ‘Nothing beside remains,’ wrote Percy Bysshe Shelley. ‘Eternity,’ wrote Arthur Stace, knowing it couldn’t last.

In mid-November, 1947, an Unnamed Woman was detained in the Central St Police Station, just a couple of blocks up from Haymarket. Detectives pecked at her for a few hours and then they let her go, once she had signed this odd, exhausted testimony – – poetic because it’s so blunted – – which I found in the archives of the Justice & Police Museum down by Circular Quay.

I am married to Frank K***** but I live apart from him and we don’t argue these days. We have one child and I have called her Maureen. Because I don’t have a house of my own I live with my sister Beryl and her husband Harry. 20 Simpson St Bondi. The furniture in the house and the carpet and the lounge suite and the wireless and the curtains and blinds and the cabinet and the glass vase and the crockery and the sideboard all belong to Beryl. I have one bedroom with my child and it has a double bed and my child has one loughboy and I have the other loughboy. We share the dressing table. I have a Mullard wireless set but it is on the ice chest in the kitchen and we all use it. I am a barmaid and I work in town. I go to work by tram which I catch in Curlewis St. It goes up Edgecliff Rd and Woolhara and Darlinghurst. I have a square mirror in my bag but it has no stand on it. I was a nurse for two years. I have no relatives named Stewart at Mt Colo.

Signed ————– .