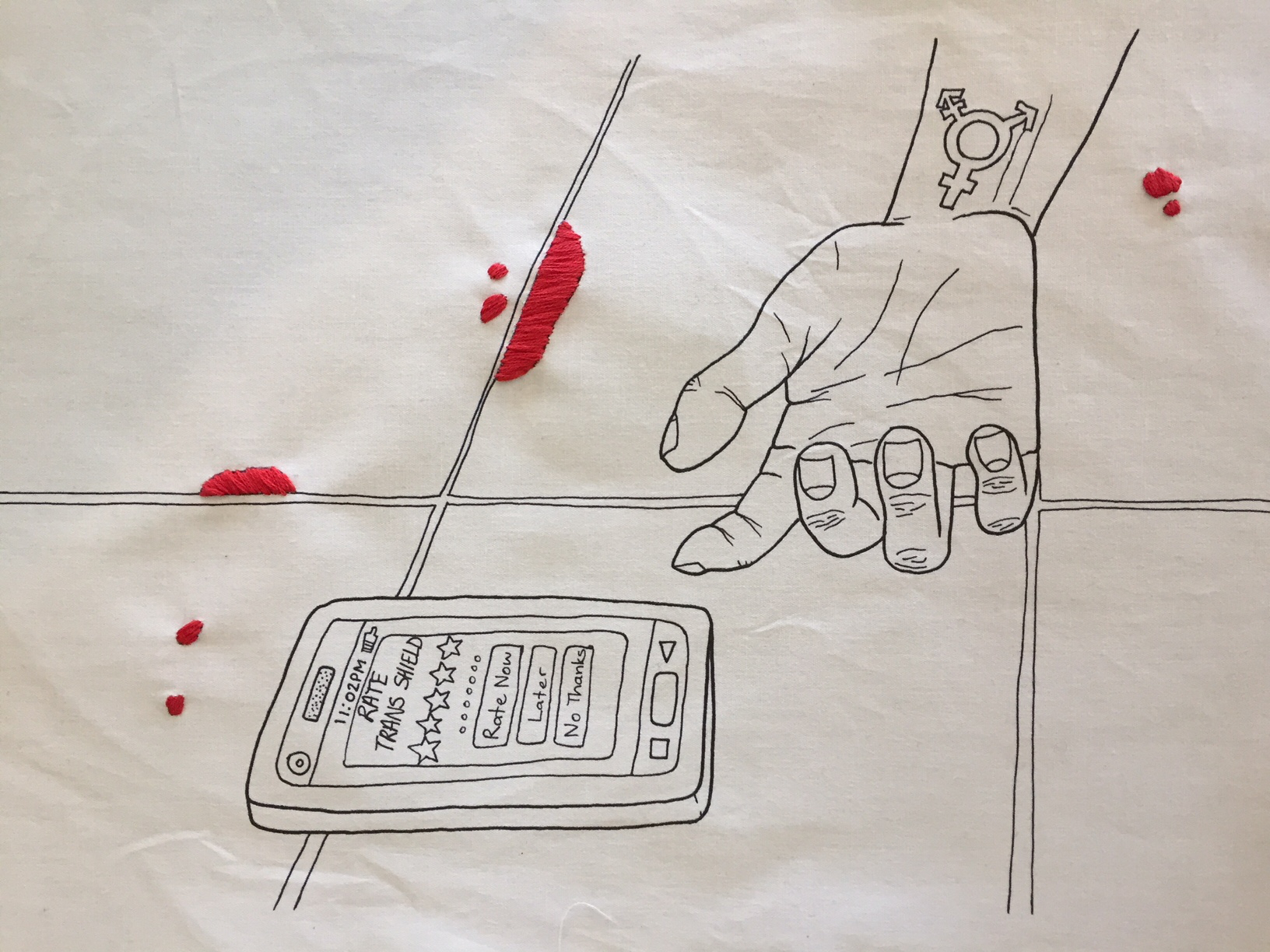

‘Do more, do better’ is a poem in four parts that explores transgender discrimination through a hypothetical augmented reality (AR) mobile app. The accompanying inked and embroidered art pieces reiterate key themes within the poem using a medium that could be considered an analogue to tech culture’s digital: craftivism. In combining elements in alternate modes, the pieces point to the ways in which these media may have commonalities, but may also be divergent. This aligns with the subject matter of the poems, drawing as they do on the everyday experiences of trans and gender diverse folk within public spaces. Public spaces should be safe, but are instead revealed as fraught with the threat of, and direct instances of, public violence.

In the first stanza of the poem, a new mobile phone app for transgender, non-binary and gender diverse people is introduced: a Band-Aid, a quick fix ‘until society catches up.’ This is not a trans utopia, but the creators of this app are doing their best with the tools they have at hand. The illustration of the Trans Shield logo is half embroidered in satin stitch while the other half is unraveling, trailing threads that fray and fall away like bandage fibres covering up an old wound, reiterating that this app is only a stopgap. In the poem, the question is posed: why do we ‘see [trans people] differently’ and why should an app like Trans Shield be needed in the first place? Indeed, the title ‘Do more, do better’ asks the reader as well as the wider community if they are doing enough for trans people and others in marginalised communities.

The second and third stanzas of Part 1 acquaint us with the ‘bloody upsetting’ realities of being trans and gender diverse, like being ‘politely misgendered,’ and highlighting the simple changes people can make in their lives in order to make trans people more welcome: using correct pronouns and terms, and respecting trans identities. The use of ‘polite’ is heavily ironic, demonstrating that politeness does not result in inclusive discourse and can be used to deliver a microaggression. Sonny Nordmarken in Transgender Studies Quarterly defines microagressions as commonplace, interpersonally communicated ‘othering’ messages which either intentionally or unintentionally relate to a person’s perceived marginalised status (Sue, 2010; Nordmarken, 2014). Part of the cruelty of microaggressions is that they come from friends and family as well as enemies, and here the politeness is positioned as an essential aspect of the misgendering, making it a ‘bloody upsetting’ reality for trans and gender diverse folk. The use of humour and sarcasm in these stanzas and throughout the poem draws upon the idea that comedy can be used to cope with the anxieties of life, and can have a beneficial effect in response to both positive and negative life events (Martin, Rod A. et al, 2009). The reader can laugh at and relate to just wanting to ‘buy / your fucking groceries,’ but this poem stresses that when you are trans, this simple domestic experience is often fraught with ridicule and dehumanising misgendering.

When reading these stanzas, augmented reality (AR) games like Ingress and Pokémon Go probably come to mind – games that layer our reality with computer-generated perceptual information. In the case of the fictional app Trans Shield represented in the poem, these data include multiple sensory modalities such as visual and auditory augmentations (Schueffel, 2017). While a game like Pokémon Go can layer your boring walk from home with competitive gamification, Trans Shield promises to shelter you with layers of trans-inclusive AR, turning an antagonistic walk home into a peaceful one. This does not, however, as we see later in the poem, remove the physical violence of transphobic attacks. It also does not change the structural transphobia of mainstream society.

The fourth stanza presents us with fantasy tech jargon, stating the app ‘syncs with your / BrainChip’ and uses ‘the latest / AR breakthroughs’ to give the user visual and auditory peace of mind. The line ‘glazes of hands / and sign language’ reminds us of the intersections between marginalised communities, in this instance the transgender and disabled communities. It is important to remember that ‘a voice / and mouth’ may not be a sensory option for everyone and that experience is intersectional.