K/

In Garbage Ammons writes:

garbage has to be the poem of our time because garbage is spiritual, believable enough to get our attention (18).

I can’t get away from this idea that garbage is spiritual. I am always looking for the spiritual. I joke often that I was raised a heathen. My family seemed to worry when they found me reading the Bible, especially unsupervised. The pagan texts were safer. My mother believes in ‘something’, feels twinges. My dad was cured of faith by Catholic boarding schools, the scars they left, the contradictions. Asked to write a wedding poem for my brother, I rang each member of the family to ask their beliefs. My oldest brother is an atheist, but believes marriage is sacred. An army padre waved the prop of a tennis ball as he conducted the ceremony in an army hall.

That tennis ball is likely in landfill somewhere by now, or else a decaying layer of earth. I remember as I write this an American photographer Don Hamerman – walking his dog in the neighbourhood, he finds lost baseballs, also decaying. He takes them home, and eventually photographs them, makes portraits. I have prints of a few. The portraits vibrate with personality.

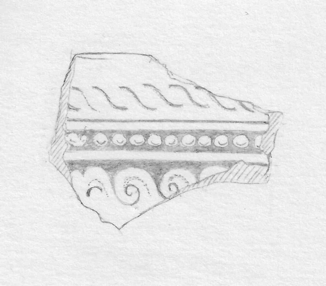

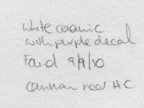

In Vibrant Matter Jane Bennett happens upon a configuration of debris and sees it as vibrant. I once mentioned my own understanding of the rock mind in a poem – a panpsychist reading of the aliveness of things that perhaps chimes with Bennett’s vibrancy. The cracks that appeared that led to those shards – were they the inevitable response to clumsiness, or some will in the clay? I think of Bennett noting the uneven distribution at the atomic level within metals, the instability that emerges over time. And I think about gold. I learn that it is a ductile metal. Ductility a particular resilience. Gold sits at one end of a brittleness/ductility spectrum. I think about brittleness: about the shards again. About other shards to come – the plastics of the past century cracking up. I think of words like resilience and brittleness in terms of emotion, as reactions to trauma. The ideas expand and fragment at the same time. The poem I write as I look again and again at the images S. gives me becomes a poem-essay with multiple centres.

In Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories Elizabeth Freeman names chrononormativity. The schedule that the traditional marriage plot strongly suggests. I listen to an interview with the author, and a question about queering time. I think about the ways in which that tea time, that break, taken off clock time, could be resistance. And I wonder if its shattering across the ground of Hill End is a queered time or the return of normative time. Explode restfulness, be productive. I can’t decide if which temporality the cracks belong to. I think about the weird schedule of creative time. The burst of ideas S. and I shared, then the months of going dark, then a new frenzy of – if not understanding, certainly new questions. Thinking and making and following attentions: these never fit into clock time.

Or Jenny Odell’s How To Do Nothing: I dwell in her concern with bioregionalism as a redirection of attention. She talks about learning local plants and birds, but also about the sociology of place, about garbage. As artist in residence at a dump, she found materials. In Hill End, in walks around Leichhardt and Iron Cove and Balmain, I find material too. I think with walking, and I think with rubbish. One is a remedy for my body and my mind, both disordered. The other disorders me. In the unsettled space between these states I try to make something of the friction.