There simply is no easily had “brief record” of modern and contemporary little magazines held by the University at Buffalo’s Poetry Collection; even if we were to divide by era, geography, or special interest—there are, after all, over 9,000 such little endeavors held. I have decided instead to pull a random sample of these little magazines—those with titles beginning with symbols or numerals, marked “Shelve at beginning of alphabet.” This is, approximately, a mere two shelves from the archive’s total holdings of little magazines—two shelves from 1,260. 1 These readings are meant to be cursory, to advertise for and invite future enquiry.

+R

Officially, the Poetry Collection does not collect collegiate publications; to do so would go beyond the intended statement of exhaustiveness, far more prohibitive in time even than by funding. There are of course, as with all rules, exceptions: and these would be instances of otherwise significance: collecting by region, by notable contributor or editor, or by meritocratic hindsight. +R , per editor Bill Brown’s preface, was born out of “the cancellation of The Black Mountain II Review,” for which Brown had served as editor. 2 One may thus materially traces the transfer of Black Mountain influence from North Carolina to Western New York, in step with the professional moves of Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. According to Brown, funds continued to stream in following the demise of the former magazine, needing allocating.

Born of excess, the title takes its symbolic translation from the French “plus d’aire”, “and it can be translated as ‘(no) more air,’ that is to say, both ‘no more air’ and ‘more air.’”3 Well noted: the University at Buffalo’s simultaneous intellectual ancestry to French theory. (Through the editor’s affiliation with UB, the magazine states clearly its academic happenstance, with especial regard to funding.)

The back cover—as often—serves as shortlist table of contents, boasting poetry, narratives, criticism, and graphics. One finds poets at work in the Buffalo academy at this time, like Lisa Jarnot (whose biography tells the collector that she edits a further little magazine, No Trees) and Slade Adamson (contributing a “Poem-By-Numbers” piece among other works, including “To R,” dedicated to Jarnot).

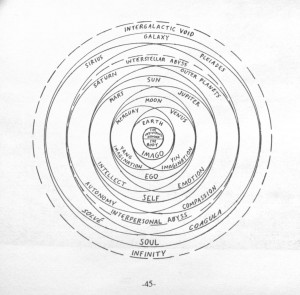

The poetics is contained in a mere 64 staple-bound black and white pages, ranging from Mikhail Horowitz’s spatial-musical ekphrasis, “Dave Holland Trio,” to Joseph Brennan’s Phillipsian cross-out texts from Behavior of the Orgasms , to the diagrammatic “The Metasphere” by Joseph Kerrick (below) accompanying narrative excerpts from The Passions of Secret Gods.

Fig. +R

0 to 9

Vito Hannibal Acconci and Bernadette Mayer began this New York-based endeavor in April 1967. Rife with cipher aliases (presumably for Mayer), the contents bridge categorizations of the visual and the poem writ time and again, including contributions from Hannah Weiner and Jasper Johns, Dick Higgins and Sol LeWitt, Clark Coolidge and Robert Smithson. Issue One also carries an interview with Morton Feldman.

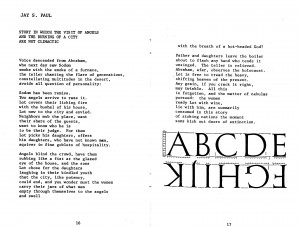

The format is large, American standard, 8½” by 11”, side-stapled in that archivally frustrating way—far cheaper in cost, unable to hold together well over time. The cover of issue three brings together that signature mimeograph typescript with a hand-stamped alphanumeric titling.

Fig. 0 to 9—a

and features a lushly laid-out “Six Works” by Clark Coolidge, in which three or so words island in the center of the page-field—something commercial publishing might not have afforded to a minimalist and as-yet uncanonized poetics.

And No. 4 ran Jackson Mac Low’s early “biblical poems.”

Fig. 0 to 9—b

019890

This was more of a Buffalo music zine, transferred to the Poetry Collection within a cache of publications collected during the heyday of Hallwalls. Hallwalls is central to understanding literary, visual, and performance art in Buffalo from the 1970s going forward. Founded in 1969 by Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, and other local luminaries in the visual arts, many (like Sherman) had been students at Buffalo State College (another branch of the State University of New York system) back in a time when public funding was rife.

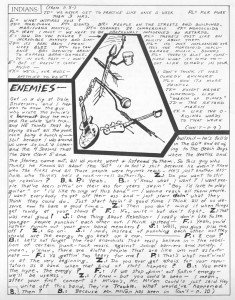

I like its newspaper-like page layouts that cascade from cover through interior, with hand printed fonts spliced with image and gnarled declamation. “Calling all advertisers…” shouts the inside front:

019890 is being circulated in New York City, Boston, Toronto, as well as in Upstate New York and the Buffalo area. Advertising in our mag will not only bring you business, it’ll make you famous! If you want to be famous, write for our rate card at…”4

Clearly a feigned distaste for commercial funding is jettisoned here—these editors would rather extort commercial money against a return of underground credibility, or at least for a laugh.

Fig. 019890

And while the music review remains the idiom of this organ—“Interviewing this band was sort of like, well…taking a big bite out of a brick building”5—it showcases an affable fuck-all editorial (“There are no mistakes at all in this magazine”6) and gives greater depth to the Buffalo scene of the late 1970s, a time when organs like Top Stories, Inc., and Works and Days were starting up or aleady at play.

2+2=1

When Judy Shepard spoke here at the university last semester, she answered this question from a young audience member: How does a location overcome the stigma of a hate crime? Laramie, Wyoming, Shepard answered, is a beautiful place full of kind people; it is also where a despicable hate crime was committed against her son in 1998. Extending Shepard’s words: It is poetry’s place to go to and come from everywhere. Laramie is no exception, and it is where this poem (in excerpt here) by John Macker was published, circa 2000:

equinotcial for Annie

(after Bob Kaufman)our Tibetan Om flag waves

narcoleptic goodbye in the slightequinoctial breeze; manana:

the desert has broke the back

of winter.

When I was born, the last Jesuit

was martyred in Mozambique &

my lives became synonymous with

white buffalo moon

the cotton candy sadness of turquoise

sunsets

digital rattlesnake

The page trim is double that of the folio—twice that of the quarto-sized 0 to 9; four of an octavo like +R —displaying expansive terra cotta landscapes of print and visual text, as with this page featuring Elizabeth Winder and Ronald Rowe:

Fig. 2+2=1

3¢ PULP

The archive holds only one issue of this twice-monthly folded broadsheet from 1970s Vancouver.

Why not from Kris Larson’s “A Euro-Agrarian Dream”?

A curvature in the road

and a dark sea, almost paintlike.

Long white farms led to it

on the glacial pasturage of hills.

I was awoken by the sound of a chainsaw

I thought was a cow bellowing

from one of the fields. 8.]

3×4

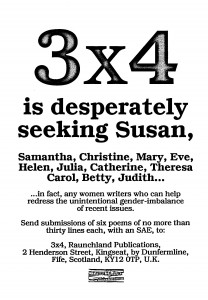

Purest in its approach to the little magazine, this version, edited by John Mingay, presents four voices (generally, though not, as with any proverbial rule, as rule) in folded and staple-stitched papers, issued from Durham and Fife, England between 1989 and 1995. Its numerical poetics of three poems by four poets is a popular one, popularized by such later examples as Brooklyn-based Ugly Duckling’s 6×6 (below). Among its investment in many not-so-well-known poets it also carried Harry Guest’s “The Lion of Venice / in the British Museum,” reminiscent of the modernist ekphrasis by icons like Ezra Pound and Marianne Moore.

I include here 3×4’s “desperately seeking Susan” call, exhibiting the politics and attention of one editor to gender, and the kinds of calls one comes across enclosed within these small issues. Also, this (instead of an) editorial: “No reviews. No editorial. No adverts. No graphics. No squeeze.”

Fig. 3×4

3-D Roadmap to Hell

Poems know no territory, and so again with the zine; this one replete with cartographic papers for backdrop: all poems, travel diary entries, and illustrations are pasted on top of reused maps. In one such issue, and presumably penned by editor Dee Allen, one finds a metatextual edit where Bayonet Pt. meets Bayonet Point—both geology and geography are encircled, with an arrow from print reading “I WANT TO MOVE HERE.” 9.]

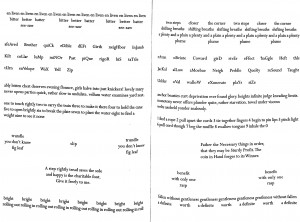

3rd bed

Expansive funding does not dictate expansive poetics. But in 3rd bed the format meets the poetics: trade sized for savvy retail; resilient matte covers; a poetics expansive in that it moves the field of the page to include the critical, the graphic, and translation. Such formatting affords great spreads, like these (2 of 3) untitled panels by Margaret Frozena, from Issue 8 (Spring/Summer ’03):

Fig. 3rd bed

Begun in ‘98-99 in Seattle, the contributors tend toward the unheard of, or—more likely—the student group, herein finding a serious and well-(at)tended forum. 10 Large commitments in trim and expenditure also require largesse in staff, and this biannual waved a masthead of founders, patrons, benefactors, and supporters. The journal also bears some connection to Brown University, at one point giving a prize judged by none other than the Waldrops and Amy Hempel.

All in all, the endeavor grew through eleven numbers, eventually including a section headed: Chapbooks, Excerpts & Novellas. No. 10 is prefaced with manifestos plus Yankevich’s translation of Daniil Kharms’s “The Saber.”

THE 3RD THING

Fig. 3RD THING

Sticking to archetype, this mag ran for one issue in the summer of 1974, edited by Shaun Farragher, unbound and folded within heavy cloth-textured prints. A mix of the literally charged erotic with the illustrative does not dilute the rayographs by art editor Marlene Tartaglione, nor Barbara A. Holland’s

Who else

skims in heroic

shadow

down a rain-bright street

on tread of whispers,

in certainty;his hope-filled satchel,

heavy with eventful futures,

slung over a possible

wing root? 11

4 ELEMENTS

Claiming the poetics of a poetry review, these lean numbers ran ads plus the ever-interesting occurrence of a published list of its contributors’ addresses; this is a common feature of the smallest of the small, where coterie is so likely yet tenuous that the magazine courts influence through and outside its own bounds.

There are at least two known issues of 4 ELEMENTS, both dating from the mid-‘70s, the second showcasing this poem by Jay S. Paul of DeKalb. 12

Fig. 4 ELEMENTS

4 New Zealand Poets

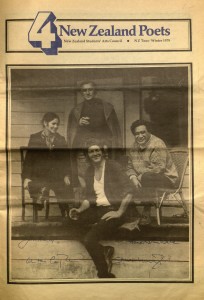

Published by the New Zealand Students’ Arts Council in the late 1970s, this newspaper-styled journal brings together—you guessed it—four poets from New Zealand, in an expansive field of poems, photos, and the social.

The Poetry Collection holds only Issue Two, featuring Alistair Campbell, Sam Hunt, Jan Kemp, and Hone Tuwhare, each having signed the cover in blue pen.

Fig. 4 New Zealand Poets

4th Street

This is what Poetry could have remained, with less budgetary and more coterie.

4th Street is quaint in an utterly non-pejorative way, its contributions at times so macabre I want to weep happily. Its trim is the supple and slender octavo; its expense heavy resume-like free endpapers. It even features a page “0” at the beginning of each. For biographies, it offers “Name Droppings” and postscript by editor Wendy Ortiz, of Inlet Press, Olympia.

For poetics, it takes invitation seriously: the scope spans schools like it’s its mission. And even with only 12-16 pages of print, the editor isn’t afraid to give six of those to one poem. It appears bimonthly. It is also not afraid of confession or of experimentation. It develops a stable, like most magazines do in kind, and from these we learn Pam Ore (“I can write an alphabet, / Then: I can make a cage. / Language is the key singing in the lock.”13), Curt Duffy (“girl girl girl boy girl / boy Wed girl boy girl boy / boy girl girl girl boy boy” 14), Brandi Dreery (“be my beak / my fall, lover / fuck me liar / fuck me over” 15), Bill Yake (Floating in the turquoise Bismark Sea above sunlit worlds, supple. Soft coral. Salt wave.”16), and Amy Holman (“To cosset is to make a pet of a lamb / without his dam: coss, kiss, kyssa, cosset. / I’m woolly, too. Lust is from / listen – to please…”17).

Perhaps my samples reflect too much my taste. What of the November/December issue, 1999? These four excerpts in sixteen slim pages:

You wished the sea could talk

You thought it would comment on

Human ballast jettisoned from cargo ships

Of slaves, money be damned at a time like this18—

O emotions sulking on the sofa

What are you sad about? A candle on the mantle?

The Shoji screen? Recalling Rimbaud & Reverdy?

You are feigning for my sake.19—

200 billion gallons—

tritium, cesium, strontium, iodine-129

contaminated reactor water

creeps a thirty year pace

through the Hanford aquifer

towards the Columbia river.20—

and sing words salmon fingerlings

salal and huckleberry

they sing Makah Nisqually

logging clear-cut fir fern trillium

they sing of Seatown and P-town

railroads and hot shot freight trains

through mountain pass river valleys21

Atop all this unlike splendor, 4th Street also carried off publishing early work by Vanessa Place, and the laughing rubric “Good Poem/Bad Poem” by Neal Bailey.

Fig. 4th Street

5am

From Summer 1987 through the present, Ed Ochester and Judith Vollman (alongside a cast of changing coeditors) have curated a newspaper-formatted journal called 5am, trim on par with that of TLS and APR. Difference being—for all its widespread spreads and scope of contributors—5am does not adhere to any officiousness.

Take, from the second issue (Winter, 1988), these declamations by Polár Levine, along the lines of Madeline Gins’ What the President Will Say and Do!! (Barrytown, N.Y.: Station Hill, 1984), here in the style of the inquisitor:

Haven’t we been Eisenhowered long enough?

Haven’t we been do-nothinged long enough?

Haven’t we been fast fed?

Haven’t we been hatchet-jabbed?

Haven’t we been ashrammed?

Haven’t we been X Ray Gunned?

Haven’t we been New York New Yorked?

Haven’t we been Judy Chicagoed?

Haven’t we had our lawns mowed by some crew-cutted stranger named Bud?22

The political, the geographic, the spiritual, and the mundane—just four of many cardinals pulling narrative into fractal range.

By Issue 10 (1998) the paper quality is refined, the design more minimal, and the editors have retained—in lieu of bio notes—a list of contributors’ recent publications. The poetics still unabashed, performing command as in Antler’s ejaculatory “Caress A Flower With A Flower”:

Let starlight that left its star before the

Earth existed

caress the retina of a boy who

doesn’t know

the difference between a solar

system

and a galaxy. 23

By the thirtieth issue, the work seems calmer if no less politically inclined (left), and 5am remains unafraid to publish the young or the unheard of. Quietists reign here, as with Kathy Engels’ fussy tanka “—after Muriel Rukeyser”

Windmill tilts me sun

mill melts me cormorant talks

to me mourning doves

souls me church bell confuses

me grass grows inside me.24

5&10+2

Maths aside, this is literary review as little magazine.

Littered with editorial and a scattershot of poetry, the review makes short work of ten books per tightly wound issue. The dominant voice that emerges, however, is that of publisher Maureen Williams, locust bird among locusts:

The BBC has long been split into two linguistic factions: old guard purists and new guard libertarians. A recent dispute between these two involved the changed name of the capital of China. Although it had been declared official policy that the BBC should use Beijing, stated to be the correct name of their capital by the Chinese themselves, the purists reverted to the name given it by the British: Peking. The result was that a listener knew to which faction the broadcaster belonged by whether he or she said “Beijing” or “Peking.”25

5’9”

In the ‘70s, taking a cue from Kostelanetz and from found poetry, Al Drake’s Happiness Holding Tanks began to issue “assemblage” issues: contributors sent a thousand or so samples of their own work, and the editor collated these into 1,000 editions of the issue for viral redistribution through the contributors. Enter, circa 2005, Medicine Hat, Canada’s 5’9”.

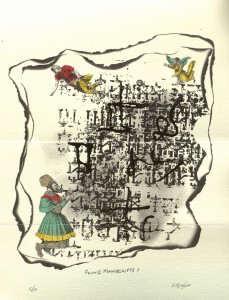

Fig. 5’9”

Editorial attributed to derek beaulieu, these wrapped or banded hand-fans—from the mimeo to the typo, the button-in-a-bag to the stencil—remind, as with Carlos Luis’s “Found Manuscripts I” (above), that collage is the medium of the 21st century.

5th Gear

“Free” is another term associated with the stapled and the small—Rarely does the small publisher see a profitable return, and so the gift economy of poetry. No exception in 5th Gear, an ever-changing format of photocopied papers out of Virginia, late ‘90s. Edited by Andy Fogle, issue sixteen came out the day after Valentine’s Day, 1997, on the editor’s twenty-third birthday, featuring this from Graham Foust’s “Official Transcripts”:

On this day

In history, there were no executions, layoffs,Rings exchanged. I have the potential for

Potential; I can even get vertigo underground.

As I speak, my papers crossA border, disheveled and unread26

5th Wall

There’s something winning about the care that goes into a library’s making containers for unique objects. The Fall 1998 “yellow issue” of this mag is snugly housed within an envelop glued to meet its dimensions (14 x 5½ cm, staple-stitched), envelop then pasted inside gray boards, with green cloth spine; it’s not handsome, but it sure is homely, in each sense of the word.

I give you, from the tiny, S. Harris’s “The Alphabet in alphabetical order”—

Fig. 5th Wall

6 Hz

Sometimes the lil mag is a broadsheet. This can be spun from the home laser printer, folded, taped, and mailed. It can be internal, sent only to friends, biweekly, monthly, for only one year; yet it may still foster a poetics, such as: “in chaotic interest pertaining to word placement, uncommon literary themes, strange diction, transcendent locution, and other delves into audience compensation for physical absence…”27.

]

6ix

Rooted in a Bay Area-Philadelphia-East Coast trifecta of Language Poetry, these ample pages gave freely of Vol. 1, No. 1 to “Draft #7: Me” from Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s ongoing epical meditation-mediation, an excerpt from Dodie Bellamy’s The Letters of Mina Harker, plus poet-publisher of Singing Horse Gil Ott and a young Melanie Neilson, cofounder of Brooklyn’s Big Allis.

The trajectory may at first appear typical: the second issue swelling in contributors, and doubling in size. Vol. 2, No. 1, though, from 1992, offers the same lush standard trim, with over half of the issue designated for one poet’s work: Kathleen Fraser’s “Etruscan Pages”; a similar redux in the following issues, with roughly eight poets sampled; and with Reviews appearing at the rear of Vol. 3, No.1 (1993).

Eventually the volumes take a second slice from Alice’s cake, evolving into a trade-like journal, once yearly. Still, these revised and cleaned-up pages are able to fairly present the expansive field of Mickie Kennedy’s “White Noise” (below), as well as Jonathan Brannen’s residually footnoted sonnets “from Deaccessioned Landscapes.”28

Fig. 6ix

6×6

When I was a teaching adjunct, this was always a student’s favorite when examining small press exemplars. As mentioned in 3×4, the poetics is fitting: six inches either way, with six poets inside, each contributing six poems. Let loose from Ugly Duckling Presse, the artifact of the example must also present; therefore, a notch taken out of each upper-right corner to unsquare the form, and every issue’s signature held gently together in a fat rubber band.

The covers are lovely, for even indie print shoppes develop standards of brand recognition: the 3-D font for issue number; the (sometimes) surprising couplings and triplings of contributors; the use of the first line of the first poem from the first poet for issue title. 29 Consider no. 7, “i will give your back”: David Cameron, Steve Dalachinsky, Joanna Fuhrman, Jason Lynn, Tomaž Šalamun, Jacqueline Waters.

10 point 5

Interdisciplinary—and this is the 1970s; it took a while to get back to this mode it seems.

And if not for, one wouldn’t find Mark Garrabrant’s companion pieces of conceptual happenstance, “How Some Move” and “Shadow Box.”

Fig. 10 point 5

10×3 plus

This editor’s poets are John Kay, Lisa Zimmerman, Marilyn Dorf, Michael Gessner, Martin Turner, Tomas De Faoite, Wendy Mooney, Ralph Culver, Grace Cavalieri, and so on. Here, ten poets, three poems, plus remainder; you do the math. This is how geography is bridged, networks forged. The little magazine remains the evidence printed in sand for a short time after the luau.

The 11th Street Ruse

It had something to do with St Mark’s Poetry Project. It was mimeographed. It editorially crossed out its own columns. It featured bylines from the likes of Violet Snow. It ran a Vocabulary Kornur that taught you words like “Tunguska” and “tungstic.” It offered a posthumous interview with Kurt Cobain, another with O. J. Simpson. It followed up with a Vocabularee Review. It even offered this limerick, “Size,” by Rick E. Lim—

There once was a woman named Thesaurus,

Whose skin was remarkably porous;

She stood in the rain

In Bangor, Maine,

And became the size of the Mormon Tabernacle Chorus.30.]

And it makes you wonder if something of poetics isn’t tied to technologies, and that in the coming of the digital something wasn’t lost.

12th Street

This is the vanguard, or a consideration of what’s vanguard, from 1940s New York, written and published by students from the New School. Like its famed institution, the magazine deals with many questions of European intellectual ancestry in the modern American metropolis—most notably as these pertain to questions of Marxism, assimilation, discrimination, and—as the quarterly progresses—aesthetics.

A few notes from Vol. 1, No. 4 (1946): Eugene Boykin’s “Civil Rights and Discrimination” noting comparable “Examples, ‘Minorities,’ Immigrants, Jews, Catholics”; Reuben Abel’s investigation of The Great Man, or Carlyle qua Marx; reviews of Huxley and Santayana; Jean Rhys, Associate Editor!

What fascinates most is the growing inclusion of poetry, symmetrical with changes in format, as the thinly printed quarto became the heavy papered octavo. After 12th Street begins including poetry it will become a mainstay of the journal without dissolution of its political inclinations, asking significant political questions as they pertain to poetics. Vol. II, No. 2 (Spring, 1948) carries a poem like “Against Secularity” by Albert H. Ledoux, plus Karl Marx’s “Alienated Labor.” The sieve of politics does not refuse its own scathing, and 12th Street remains affectionate toward the polemic and the critical.

The coinage of “vanguard” comes by way of Cedric Dover; he writes, in his clustered review of two 1948 anthologies of “young writers,” 31 on the statistics on canons. Specifically, Dover tallies the genders and ages of each contributor—and this over sixty years before Amy King’s gallant VIDA headcount.

Eleven of Professor Wolfe’s authors are women, twenty-seven are men. The average age of the women is twenty-eight, of the men twenty-nine years, but three of the women and eleven of the men are above thirty. Nevertheless, the group is described, inevitably, as young. It is as old as Henri Munger’s beard.32

Allusions and archetypes aside, Dover goes further, plumbing the gender of influence in and across the sexes—in his words, “[t]he influences acknowledged by the group add further details to its composite self-portrait.”33 Contributors were asked to list authorial influences, and Dover categorizes his table as follows: Classics, Minor European Classics, American Classics, Modern Europeans, Modern Americans. (And it is interesting to note how and where Woolf falls on these axes.) Thus we might read Dover’s analyses with intrigue—

There is no evidence of purposive reading for style or large literary perspectives in the thirteen minor European classics, three American classics, thirteen modern Europeans, and seventeen modern Am[e]ricans mentioned by the mean. The revelations of the women are still more shocking: all but four of their thirty-three authors are assorted moderns.34

The above would be enough to reopen 12th Street as a site of investigation. By the end of its run (the Poetry Collection’s copies end with Spring 1949), the dimensions of the quarterly could no longer hold its poetics: the last issue is bifurcated into two companion volumes, one the Faust Issue, the other the Poetry Issue. The latter’s contents includes David Gascoyne, W. C. Williams, Earle Birney, James Broughton, Harold Norse, Weldon Kees, Lysander Kemp, David Ignatow, Oscar Williams, and more.

15 Minutes

(Citing Warhol,) this single issue probably fell into the archive because the editor published a poem by Gerard Malanga. But it tells a lot about post-punk influence in St. Louis, Missouri, circa 1990. Contributors from Bowle Movement to Sandra Moanium could tell you about music, furniture, punk cinema, and review “the first female-to-male transsexual love story,” “Linda/Les & Annie,” while running ads like AIDS IS KILLING ARTISTS / NOW HOMOPHOBIA IS KILLING ART along those for local businesses. Zines are ever overtly demonstrative: of locale, of engagement, and of community support.

21st Century

While its wag doesn’t always match its swagger, this “magazine of a creative civilization” remains of interest primarily for its revealing discussion between Sydney and California in the 1950s. Handsomely in original covers35, this is little magazine as postwar publication, willful as the year 1913 to charge ahead of the past.

Fig. 21st Century

24-7

Subtitled “Rhode Island Art and Literature,” this free publication bears witness to the livewire poetics of the 1990s zine. With black and white newsprint pages and a touch of red splurged for for cover title, 24-7 harkens to an interdisciplinary page exemplary of a poetics cantilevering poetry and music reviews with social politics and the visual, like this spread from Vol. I, No. 3(1994), “For the South Side I” by David Baggarly—

Fig. 24-7

Issued in runs of “500+”, the publication was distributed for free; and whether the contents relays authorial or aliased bibliography, the span remained topical in a way that today’s fracturing makes seem lamentable. For instance, Vol. 3, Issue 1 boasts Allen Ginsberg in conversation next to a review of Lisa Loeb, over a dozen poets plus a feature of work by Sylvia Moubayed, and editorials on road-tripping the American Midwest, why “Björk is the best musician of the past two decades,” and “Gay youth in the 90’s.” These alongside gallery reviews and music ones, ranging from hip hop to grunge and alternative.

26

The project of collaboration as it configures an editorial is an interesting one, and not without interesting projections of a poetics. 26 took this as template when Avery E. D. Burns, Rusty Morrison, Joseph Noble, Elizabeth Robinson, and Brian Strang gathered in San Francisco’s Bay Area, refusing consensus, and started out with issue “A.” Translations were welcome, as were essays and reviews, alongside a civics engaging with the milito-political, as exhibited Andrew Joron’s “Statement on War & Terrorism” (this is early 2002), which later went viral. And while west coast-centered, the editors—presumably through call, suggestion, and deliberation—arrive issue and again with a broad wingspan of selective inclusion.

By issue F only two editors remain, Burn and Strang, signaling a closing down of the projected abecedary of issuance. Close to the end of the last, this again from Joron:

The swing of the pendulum represents not propagation but merely alternation. Unlike the alternator, the propagator never returns to an initial position. Once that light that inhabits fails, it fails with finality.36

(And this, 2007.)

80 Langton Street

Sometimes the periodical is a flurry of correspondence, relaying the accounts of a scene in formation. Such is the case with this Artists and Critics in Residence program, and its circulars posted to like-organization Hallwalls, in Buffalo, illuminating the goings-on of San Francisco throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. These fliers, postcards, and catalogs inform partners-in-the-arts of daily happenings, and leave trace of the burgeoning of scene.

Through archival troves as these one learns of these happenings:

April 1977 “eye music” film series emerges.

Oct. 1977 A month long exchange occurs between Tokyo artists and the Bay Area.

Dec. 1977 Michael Auping serves as the first critic-in-residence.

April 1979 Alison Knowles performs Natural Assemblages and the True Crow.

Sept. 1979 There is a showing of films by, with appearance from, Red Grooms.

Nov. 1979 “Masters of Love” group show opens, including Robert Longo.

Aug. 1981 Kathy Acker curates “Extravaganza” w/ Factrix; Lyn Hejinian serves as writer-in-residence.

Jan. 1982 Mal Waldron performs with Jana Haimsohn.

March 1982 Bob Cobbing performs sound poetry with P.C. Fencott.

July 1982 Allen Fisher serves as writer-in-residence.

This is cultural ephemera of the first order, from the calendar to the reception notice, like this one from Sonya Rapoport’s “netweb: objects on my dresser.”

Fig. 80 Langton Street

88

Just after the last would be-zeitgeist, on-demand printing started making glossy, perfect-bound journal publishing available to editors everywhere, including Hollyridge Press of Venice, California. Founding editors like Denise L. Stevens and Ian Randall Wilson could now make new and inclusive choices, as shown in Issue 2 of 88, without the stricter limits of finance and school: yes, kari edwards; yes, Rachel Hadas; yes, Terrance Hayes; yes, Mark Jarman; yes, Jeffrey Jullich; yes, Terese Svoboda.

96 Inc

Ubiquity may be better by nature than by artifice when poetics. Sometimes the organ is a sign of one geocommunity. The editors of Boston’s 96 Inc advertize their poetics through the blurb “[i]t’s a bit like a patchwork quilt…the more disparate, the merrier.” 37 With a board as long as its Contents, these local journals may sometimes, amid diverse effusions of taste, display the early output of a Louis E. Bourgeois, or the sheer ubiquity of a Lyn Lifshin.38

108

Of 3rdness Publishing, )ohnLowther’s Atlanta-based magazine seems involved with a countdown toward issue “one”—featuring a special DC Poetry issue, edited by Tom Orange, for number 92—as presented in this afterword to issue 106:

Fig. 108

109th Street Vision

For subtitle, “The Letters of the Poets” – at least, for issue one. Thus: the little magazine in service to anthology. Presumably of previous published works (some in translation), rendered herein without admission, a curious and exciting premise persists where one reads easily between Holderlin and Rimbaud, and Pound (to Iris Barry, June, 1916) and Pound’s Li Po.

Further excitement exists between Neruda’s

My dear Rosaura,

Here I am in Iquique, under arrest.

Please send a shirt & some tobacco.

I don’t know how long this dance will last.39 Herron and T. O’Connor: 14.]

Rilke’s “to a young poet” of 1903, and Whitman’s war letter,

tried by terrible, fearfullest test, probed deepest, the living soul’s, the body’s tragedies, bursting the petty bonds of art. To these, what are your dramas & poems, even the oldest & the fearfullest?40

Why not continue in this vein, a cross-era compendium of letters?

(But by #3 this serial has become a single-author chap by Bill Herron [1981].)

The 432 Review

I become aware of what’s known as a second wave of mimeo, this example being New York Mimeo. 41 The trim size is luscious: a narrow folio; stapled along sides; in hand-illustrated covers. This is New York in the ‘70s, specifically: St. Mark’s in the wake of O’Hara. Regular contributors include Alice Notley, Bob Rosenthal, Kathy Acker, Rochelle Kraut, and Simon Schuchat. Not least of all, an issue dedicated posthumously to Frank O’Hara’s work (1977), plus this collaborative piece from a Jim Brodey feature (1976):

Fig. The 432 Review

491

Culled from the ever-nascent copulating of the sacred and profane—here a confluence of popery and Dada 42 — this is a zine from when zines were zines. Saved from its own ephemeral intent by collages from pop culture, politics, and pornography, this manifestation of a South Buffalo underground also references Dick Higgins and Ray Johnson.

Fig. 491

1844 Pine St

Taking impetus from the Beat legacy, editor david kirschenbaum blends ‘90s zine flexibility with “messy” mimeo, making bread of Waldman and Ginsberg for a sandwiching that changes pace with every turn, mixing the established with the yet unsounded. Jack Collom’s pseudo-mesostic “for Jackson Mac Low” (issue 3 or 4) along with Ann Charters’ opening remarks at the Beats: Legacy and Celebration conference (issue 1) and Matt Corry’s conceptual post-Ono instructions (presumed issue 5, below) are examples of this admixture.

Fig. 1844 Pine St

Of note on the quicksilver longevity of such endeavors, the editor’s fulfilled intent to issue only five editions in a period of five weeks.

1913

This seems an appropriate place to end—

Ben and Sandra Doller’s journal of the literary arts makes no rule it cannot break: trim never uniform, page orientation never a given, and category of poem, visual frame, or poetics need not obtain. It takes its name (presumably) from the 1913 Armory Show, famously: the translation of avant-garde Paris into its New York pronouncement. 43

Wild with the inspiration of that era, it welcomes anything that it excites in the quest for evidence of the modern, 1913’s fourth issue alone (2010) including Meg Barbosa’s sophisticatedly terse lyrics, page-frame-ups from Richard Meier’s “Little Prose in Poems,” language plates by Lynn Xu, and a digitally-negotiable paged presentation by Brad Flis; also, Tom Orange on the interdisciplinary journal Joglars, and the design-centered magazine-within-a-magazine piece “pP.” by Alejandro Miguel Justino Crawford.

In remaining utterly open to the field of poetics to come, 1913 is also grand retro-harbinger of wherefrom the little magazine’s myriad origins.

- All examples cited come from the generous holdings of The Poetry Collection of The University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, with extra thanks to my colleagues there, especially Curator Michael Basinski and Assistant Curator James Maynard. All quotations and reproductions used under fair use. While the unusual numerical titling of a magazine may seem to slant the poetics toward the radical, I think the reader will find the sampling generously ill defined. ↩

- Bill Brown. Preface. +R, No.1. Buffalo, Spring 1988: 2. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- “Now Advertising.” 019890. Emily Zane and Marlene Weisman, eds. Vol., No. 1 Buffalo: 1979. ↩

- Ibid, “Subliminal Prophets: The Indians” (interview), p. 5. ↩

- Ibid, p. 1. ↩

- John Macker. From “equinoctial for Annie.” 2+2=1, issue 3. Laramie, WY: c. 2000. ↩

- 3¢ PULP, Star-Kissed Ecstasy, Vol. II (No. 14), 15 Sept. 1974: [2 ↩

- Dee Allen, et al. 3-D Roadmap to HELL No. 3. Hamilton, Ohio, 1996: [21 ↩

- Though most contributors to the first issue are relatively unknown (to me), it does boast work by Bill Knot, Heidi Peppermint, and a critical piece by Bei Dao on Allen Ginsburg. This first issue is the only one issued in untreated and perfect-bound papers. ↩

- Barbara A. Holland, from “None Other.” THE 3RD THING, Shaun Farragher and Marlene Tartaglione, eds. 1974: 52. ↩

- Jay S. Paul, “Story in which the Visit of Angels / and the Burning of a City / are not Climactic.” 4 ELEMENTS: A Poetry Review, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Winter 1976). ↩

- Pam Ore, “XXX / XXX / XXX,” 4th Street, March/April, 2001: 7. ↩

- Curt Duffy, “Broken Compass,” 4th Street, March/April, 2002: 7. ↩

- Brandi Dreery, “Ah Yes, My Love,” 4th Street, July/August, 2000: 12. ↩

- Bill Yake, “Perspectives—Notes for Postcards from New Guinea,” 4th Street, July, 1999: 11. ↩

- Amy Holman, “Is Kissed An Orphaned Lamb?” 4th Street, March/April, 2000: 10. ↩

- Susan Maurer, “Seashine,” 3. ↩

- Kenneth Tanemura, “Touch and Go,” 13. ↩

- Mac Lojowski, “Hanford Cleanup Project,” 10. ↩

- G. Dundry, “It’s the Heyday of Poetry in the Pacific Northwest,” 6. ↩

- Polár Levine, from “Nothing is Forgotten: Song 1.” 5am (Winter 1988): 1.

↩ - Antler, “Caress A Flower With A Flower.” 5am Issue 10, 1998: unpaginated.

↩ - Kathy Engel, “Block Island Tanka Morning.” 5am Issue 33, 2011: unpaginated. ↩

- Maureen Williams, “My British, Your American: Moving the Goal Posts.” 5&10+2: Essays and Reviews, Vol., No.1 (Spring 1993): 16.

↩ - Graham Foust, “Official Transcripts” (excerpted). 5th Gear #16. Norfolk, VA: 1997. The Poetry Collection holds only three issues, including nos. 21 and 22. ↩

- 6 Hz, No. 1: supplement. Attributed to Sean Winchester. [Reno, Nevada: 1993 ↩

- 6ix, Volume 5 (1997) and volume 6 (1998) respectively. ↩

- This has winningly puzzled many a challenge-loving cataloger, as each issue presents as anthology, a serial, a group endeavor.

↩ - The 11th Street Ruse, Vol. 5, No. 4 (really). Birthday Milk Issue: [no date ↩

- Cedric Dover, “Portrait of a Vanguard.” 12th Street Vol. II, No. 3 (Winter 1949): 117-124. Dover is reviewing American Vanguard (Cornell, 1948), edited by Don M. Wolfe, and U.S.A.: A Book Devoted to the Younger Writers (Privately printed, 1948), edited by Charles I. Glicksberg. ↩

- Ibid, 117. ↩

- Ibid, 119. ↩

- Ibid, 121. ↩

- No. 2 (August, 1957) decorated by the editors and others; No. 1 (September, 1955) in burlap, with some glue still eating away at the pages inside. ↩

- 26 no. F. San Francisco Bay Area, 2007: 227. ↩

- Mopsy Strange Kennedy in The Improper Bostonian. 96 Inc No. 9, 1999: inside front cover. ↩

- 96 Inc No. 14, 2005. ↩

- 109th Street Vision No. 1, c. 1980. The letter, in the form of a poem, is to Arturo Carrion. Translation attributed to B[ill ↩

- Ibid, 21. ↩

- Thank you, Mike Basinski, for cluing me in to this! ↩

- 491, No. 15. Buffalo: c. 1976: Among many images, one captioned “Cardinals Ignore Pope’s Funeral” and depicting four cardinals, their headwear spelling out “DADA.” ↩

- As Tzara had it (and here I’m paraphrasing): There’s no need for Dada in New York—All of New York is Dada! ↩