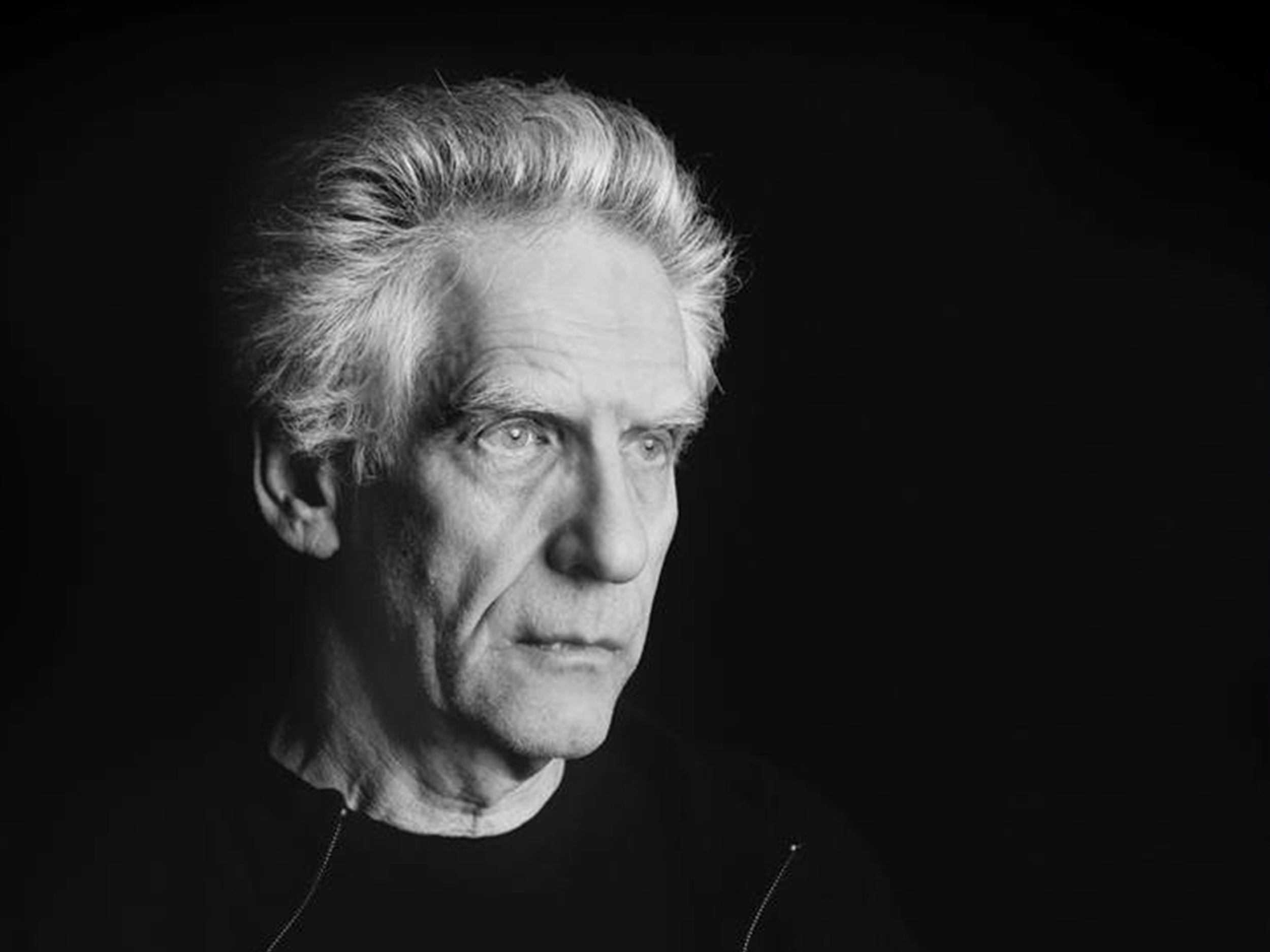

Image courtesy of Myrna Suarez / Simon & Schuster

In cinema, isn’t death a synonym for ending?

–Serge Grünberg, David Cronenberg (1)

‘It’s over. You’re finished.’ And then, after a pause: ‘Goodbye’. These are the last five words uttered by Christopher Walken in the concluding scene of The Dead Zone (David Cronenberg, 1983). His character, Johnny Smith, has been tormented, up until this point, by an unusual gift that has made him the ostracised loner within his community: if he grips someone’s hand, he can foresee the moment of their death. If they take his advice, they can alter this destiny; but many, considering Johnny to be a nut or a freak, ignore it and suffer the consequence.

In the film’s finale, Johnny takes the initiative of hiding out in a hall where a political rally is being hosted, and then firing a rifle shot at a political candidate, Greg Stillson (Martin Sheen), who he knows will, in his right-wing insanity, lead the world to a tragic, nuclear apocalypse. Stillson doesn’t die on stage, but he performs the gesture that derails his campaign – grabbing a baby and using it as a shield – and hence the world is saved from destruction. It is Johnny who, in instant retaliation, receives a fatal bullet. To Stillson (whose imminent suicide he previews after grasping his hand) he says: ‘It’s over. You’re finished.’ And to his lost love, Sarah (Brooke Adams), who tearfully bends over his body: ‘Goodbye’. We cannot tell whether his consciousness lasts long enough to register her reply: ‘I love you’. The ultimate image of the film shows the two of them, he on the floor and her bent over him, his hand falling into a position signifying lifelessness.

It’s over, you’re finished. As dramaturgy, there is something deeply Christian about this ending – a veritable echo of Christ’s own ‘It is finished’ spoken during the Crucifixion, marking both the ending of a story and the fulfilment of a mission. Johnny Smith is certainly a sacrificial hero, dying for his love of the human race. The same ‘it’s finished’ line, or close variations on it, recurs often in narrative cinema. It receives a blackly comic subversion in There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007) when, after fatally bashing in the head of his preacher-rival with a bowling pin, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) mutters: ‘I’m finished.’ And, logically enough, we hear it spoken again, rendered more reverentially this time as ‘It is accomplished’, in Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) – but with the added embellishment, here, of the film strip seemingly flaring out, chromatically, to a white void, as if it cannot bear to contemplate this momentous death for a moment longer.

Scorsese makes explicit, in this reflexive gesture, the equation between the consciousness of his divine hero and the whole apparatus or machine of cinema itself. The end of a life – the élan vital that has guided and driven the entire story – spells the end of the filmic work; and it also can gesture to the end (grand or tragic) of something larger: a mission, a way of life, a world.

Seven years after The Dead Zone, Christopher Walken is fading away once more in a final scene: but this time as a more ambiguous kind of Christ figure, the megalomaniac gangster Frank White, paradoxically both bloody-minded master-crook and community benefactor, known as the King of New York (Abel Ferrara, 1990). His demise follows the path of those unreal, slowly-bleeding-away guys who have staggered out of the Billy Wilder classics Double Indemnity (1944) and Ace in the Hole (1951) and into the contemporary context including The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (John Cassavetes, 1976), Dead Man (Jim Jarmusch, 1995) and White Material (Claire Denis, 2009): a shot has been fired, we don’t quite know if it made contact, so the plot continues until a hand reaches inside a shirt and reveals the seeping blood … Frank White keeps running until he can run no further, stuck in a traffic jam, abandoned by his taxi’s driver, surrounded by an armada of cops. We tense for the big shoot-out – but it does not arrive. Instead, same signifier of the end of a life, providing the final shot: Walken’s limp hand, this time in close-up, and holding a gun.

There are no tears, no symphonic surge on the soundtrack here, as in The Dead Zone. King of New York presents itself, dispassionately, as the flickering-out of the strange, largely unreadable, opaque subjectivity of its Thin White Duke: back from the dead (his prison term) and out in the world for a fleeting moment, Frank White gazes, moves and acts only as long as his body holds out; the moment his consciousness is extinguished, the film too is gone, like a motor suddenly shut down. In its kinetic, nervy register – Ferrara even turned the snap of Walken’s dead hand into a funky, rhythmic motif for his clip of Schoolly D’s King of New York theme song – it is like the endings of Once Upon a Time in America (Sergio Leone, 1984), Carlito’s Way (Brian De Palma, 1993) or Heat (Michael Mann, 1995), but without the oceanic waves of sentimental regret bathing those films. King of New York substitutes something else in place of personal elegy: the sense or intimation of a collective, urban, social crisis. A world in collapse, evoked in the sheer cut-to-black from Walken’s hand.

When the heroic (or anti-heroic) consciousness is extinguished, bringing a film to its abrupt or elegiac conclusion, everything seems to end at once. Francis Ford Coppola played on the grandiloquence of this device, once again within the terms of the gangster genre, in his The Godfather series, whenever a Great Man (Marlon Brando in Part I of 1972 or Al Pacino in Part III of 1990) carks it, out in the garden after playing with kids, or just falling off a chair at the end of his time. A generational line ends, or an empire, or an era. After this, there is nothing more to be seen or heard except the pure blackness or whiteness of the screen. (At least until the credits roll.) It can feel like an apocalypse for the film’s viewer, even if an actual apocalypse does not (as in The Dead Zone) figure in the storyline.

Indeed, ambitious films (beyond the routine disaster-movie blockbusters) that dare to imagine an actual apocalypse – from the bracing pulp-fiction of Miracle Mile (Steve De Jarnatt, 1989) to the cataclysm of both society and the five human senses in Perfect Sense (aka The Last Word, David Mackenzie, 2011) and the cosmic metaphysics of Melancholia (Lars von Trier, 2011) – almost always conclude with these shock-cuts to either black or white. Music composers, performers, producers, engineers and mixers speak of sudden death endings: a simply logical cut-off, where a phrase or a segment ends, rather than the ‘big finish’ rave-up consecrated (sometimes ridiculously so) by live rock.

Some films have gone even further along this sudden-death path: the odd in medias res shut-off of Limbo (John Sayles, 1999) while a fairly normal shot unspools and much remains to be resolved; or the absolute run-out of the film reel – no credits, no black strip, no nothing – after the devastating final scene of L’Enfant secret (Philippe Garrel, 1982), in which a woman confesses to her lover her helpless return to heroin addiction.

In his book Cinema 2: The Time-Image (first published in 1985), Gilles Deleuze described the ending of this director’s subsequent short, Rue Fontaine (1984) starring Jean-Pierre Léaud, in these terms: ‘he kills himself, his body toppling slowly over in a long image to become one with snow, as in a posture which has no end’. (1) In truth, the philosopher betrays a fanciful faculty of memory here: all that happens on screen is that Léaud falls swiftly out of frame, and the film cuts to black – no fall, no snow. But this mysterious ‘posture that has no end’ speaks imaginatively to a way that we often experience – or want to experience – the endings of films: as a necessary act of mourning, a leave-taking that is either going to require a long time, or indeed ‘no end’ whatsoever, that somehow keeps resonating in our heads beyond the material movie. This is exactly what Deleuze went on to theorise in his reflection on Garrel: these ‘irrational cuts’ in narrative-based cinema to the black or white screen which allow the phantom sense that ‘the series of anterior images has no end, while the series of subsequent images has no beginning’. (2)

Theorists of narrative in several media speak about the thresholds at the start and end of a story: those phases were our attention is still with the material situation or condition of opening and inspecting a book, or getting into our seat in the cinema – the initial moments when ‘your foot is not yet in your shoe’, as Jean-Luc Godard once delightfully put it – or we are just beginning to emerge from complete immersion in the story, involving a reorientation that can sometimes be highly disconcerting (all that bright sunlight out in the street beyond the cinema, how rude!). At such liminal thresholds, we can be very aware of the highly theatrical gestures of the work itself – the myriad ways it can show us into, or guide us out of, the particular, ephemeral bubble of sensation and intellection it has created. Hence all those luxurious prologues for tales of aristocracies, from The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942) to The Great Gatsby (Baz Luhrmann, 2013) via the collected works of Wes Anderson – usually replete with voice-over narration, genealogical trees, and a guided tour of mansion grounds – and those equally extended epilogues which are (as Simon Frith once pointed out) like a pop song fading out as if moving off into the distance and hence farewelling us, as the camera withdraws and rises, the image slowly fades, and the music ‘plays us out’ …

This is the classical type of ‘character walking out of the story and into their uncertain future’ trope that Charles Chaplin perfected long ago, and that comes relayed through the endings of The Searchers (John Ford, 1955) and a thousand other movies, all the way to the final shots of roomier or more experimental narrative films like Up Down Fragile (Jacques Rivette, 1995), Blue is the Warmest Colour (aka La Vie d’Adèle – Chapitres 1 & 2, Abdellatif Kechiche, 2013) or Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the 1960s in Brussels (Chantal Akerman, 1994) – where, in every case, the camera comes to a halt, placing a pictorial parenthesis around what it records, while the performer moves, increasingly smaller in the frame, toward the far horizon, whether in a desert or on a suburban street.

Beginning in the mid 1980s, a particular fad arose in popular cinema (it’s still around today), especially its light-comedy genres: the fun just couldn’t be stopped while the end credits played, and beyond them, too. So, in zany, hyperactive films including Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (John Hughes, 1986) and Married to the Mob (Jonathan Demme, 1988), as well as more run-of-the-mill romantic comedies like Legal Eagles (1986), we were treated to a cavalcade of outtakes, flubbed lines, technical gaffes, polaroids of cast and crew (perhaps as children), and even glimpses of plot intrigues and subsidiary characters shot but not included in the final cut. Ferris B’s very last moment on screen – exhorting anybody still left in the theatre (or still watching the tape or disc) to ‘go home’ – is the commercial entertainment industry’s way of playfully acknowledging and prolonging its direct ‘aim to please’ contract with the audience.

The numerous ways in which films can bid farewell to us as viewers is a topic worthy of long study by scholars, for it is a scarcely understood or appreciated area of cinema aesthetics – and yet, at the same time, something that all good filmmakers already know well, intuitively or otherwise. (Such, in a nutshell, is the history of film in relation to film criticism!) Let us consider, for example, a screen phenomenon that, to simply speak it or write it in a script, must seem preposterous: characters/actors literally waving goodbye to us (i.e., to the camera) at the end of their story. An extremely literal, obvious way of signalling the end of a movie, to be sure; but what a powerful reservoir of emotion it unleashes when expertly wielded by Hou Hsiao-hsien, stretching the gesture out over several minutes in the final scene of The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982); or Eugène Green in his ultra-Bressonian La Sapienza (2014), where young and middle-aged couples send each other sunny smiles and greetings; or John Cassavetes, as he sadly flops his hat up and down in what subsequently became immortalised as his ‘final screen moment’ in Love Streams (1984).

Then there are the movies which seemingly refuse to end, and gesture this not cheerfully (as in the comedies) but frantically: by keeping the story moving on, even in a rapid acceleration, as if to beat back those inexorable, rolling credits. This is particularly characteristic of horror movies in the manner of Dario Argento and crime-mystery-thrillers in the vein of Claude Chabrol: both these filmmakers would keep a certain frenetic aftermath – the arrival of police, the discovery of a corpse-strewn crime scene – going during the official name-parade, giving us the feeling that we are surely missing something, and that the labyrinthine plot is, once and for all, overflowing the boundaries of script and screen. This is quite different to the Brian De Palma trick, used in Sisters (1973) and Snake Eyes (1998), of stretching out the final shot, under the credits, as if to slowly drain its last vestige of life, the camera leisurely zooming or panning, seemingly with no particular goal in sight – until, at the very last second of the image’s existence (and before the stark production company logo), some small, forgotten, hitherto hidden but absolutely essential detail is revealed, such as a bright green jewel just poking out of a concrete slab.