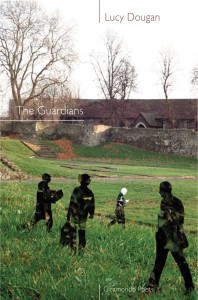

The Guardians by Lucy Dougan

Giramondo, 2015

‘The dog ran in there / It had been a mistake / to take up his old trail.’ The bold lines that open ‘The Old House’ (48) from Lucy Dougan’s latest collection, The Guardians, deliver a fine sample of Dougan’s deceptive simplicity. What better emblem for the concept of guardianship than the family dog? But the sentimental cocktail of love and loyalty embodied by this familiar friend is immediately crosscut by the ‘mistake’ of memory, an error of the senses that leads directly to the unheimlich. The protector brings us to precisely the wrong place, the site of loss. The scene here speaks for the broader interests of the collection: the intrusions of the past into the present (or of the present into the past), the rituals that make and unmake intimacies in the physical world, and particularly, the complex aspirations of watchfulness. There is a problem embedded in Dougan’s notion of guardianship that animates her poems, a dyadic relation that sets the pleasures of looking against the unsettling ethical responsibilities of custodianship, and love.

‘Atavism II’ draws the reader directly into the delights of looking:

That boy lazing in the truth of his tattoos (deep inside himself deep inside the way light from the sheet of water talks to the ceiling) (7)

‘That boy lazing’ recalls the stunning opening of Sappho’s famous fragment 31, ‘That fellow strikes me as god’s double …’ The tone of ‘Atavism II’ temporarily evokes a Sapphic scene of youthful repose, a limb-loosened sexiness that seduces both speaker and reader by wondering at what the one that is looked upon sees. But there is a swift cut away from eroticism as the speaker then surveys the quotidian view of the change-room, ‘small shoes / side by side / with the larger pair / that walked here / with them.’ A language of concern enters the poem, a touching, yet troubled vision of the care small people require of the big. Why should these two visions coincide? There’s a lovely return to Sapphic optics where the speaker observes in the mosaics by the pool:

Bodies tiled in place: a man mid-dive, a woman alert to a child, each attitude repeating an anonymous civic grace

In the triangulation of the speaker watching a woman watching her child, there is perhaps an urge to rewrite the moment of ‘alert’ concern with the ‘grace’ of pleasurable looking. But the image is suspended in time, unchanging. An urge unfulfilled, an unimaginably old artefact repeats a never-resolved watch-duty.

In Dougan’s sensitivity to alternative visible orders there is a debt to the writings of John Berger. ‘Old Sarum,’ for instance, carries his gorgeous cadence: ‘At the walls of Old Sarum we meet ourselves / … our skins as paper’ (15). But beyond such aesthetic echoes, Dougan develops Berger’s confluence of attentiveness to the sensual world with the imperatives of conscience (to paraphrase Susan Sontag). The Guardians’s poems cover a lot of ground, with villas and museums surveyed alongside old ruins, blackberry patches and abandoned homes, but rather than showcasing topographical insights, Dougan’s relation to place is perhaps best characterised by a vague sense of liminality:

We’re all like this, you see, all kaboom and splutter – who knows where we’ll fall. Somewhere between Piazza Dante and Piazza Gesù (‘Wayside,’ 12)

In a recent review-post, Jonathan Shaw quibbles with Dougan’s lack of ‘clarity’ in her sense of place: ‘so abstract in these poems that – apart from those poems where places, all but one of them European, are named – it’s not clear even what continent we are on.’ However, it might be possible to read a distinct ethical intent in Dougan’s uncertain constructions of place, which imagine only-temporary meeting zones, navigated by treading lightly. Put another way, the poetry seems to endorse a disavowal of territorialism – a form of ownership supported by the familiar sense of belonging. Dougan’s uncertain relation between speaker, subjects and terrain advances a difficult, but admirable alternative based on transitory custodianship. Loss of place, a significant theme of the collection, takes on a provocative ethical dimension. While the poems often register complex emotional responses to disorientation and loss (‘She was not ready for these feelings / that came at once together / That she wanted to hit him. / That she wanted to kiss him.’), loss itself offers the delicious secret of transformation:

I was banished to stand or squat, sometimes running my fingers over foreign ground to find the spot that might pull me down again. Death seemed lovely, the secret promise of a last embrace. (‘A Bourne,’ 51)

If Dougan’s allusions to territorial inheritances seem unsubstantial or non-specific, the effect was probably intended.

The non-specificity of place provides an excellent foil to one of the major preoccupations of the collection: the spectacles witnessed from the speaker’s position as mother. The attention and specificity here is keen and explorative, the curiosity expressing a mode of desire one suspects will never be grown out of.

and when you were tired she’d say to sit on the edge and watch (you can learn a lot like that, girls). It was always the better performance, seeing you all draped against each other. (‘Bump & Grind,’ 71)

The speaker’s description of the lead-up to her daughter’s dance concert again recalls a Sapphic vista: didactic second-person address to the ‘girls,’ delight in relaxed soft-limbs. While the logic is not strictly erotic, the youthful spirit of Sappho is the prevailing mood of the poem, even – in fact, precisely – as it registers rapid tonal shifts.

Much later you’ll slash the tutu, wear it over jeans and I will harvest the rose buds … and they’ll get dusty in a red cup on my desk the year that you start bleeding and I stop. (71-72)

The abrupt ‘stop’ dramatises the speaker’s menopause in an ambivalent exploitation of the end of the line, at once mournful and playfully flip. The Guardians consistently stages these conflated ways of seeing, working through configurations of delight, desire, and loss that inform an uncertain sense of guardianship. How do we watch over and care for what we love? The collection is subtle, its inner-logic accretive, and so will benefit from multiple readings. For all its ostensible concern with aging, decline, and ‘concern’ itself, the lasting effect of Dougan’s poetry is profoundly youthful, alive with compassion and uncynical intelligence.