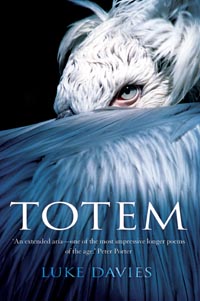

Totem by Luke Davies

Totem by Luke Davies

Allen and Unwin, 2004

I'll let you in on a secret: I think Luke Davies is in love.

OK. So it's not much of a secret. Still, while descriptions on the jacket refer to it in a variety of glowing terms (‘A sustained aria' — Peter Porter; ‘the great Australian long poem' — Judith Beveridge) what they basically elide is that ‘Totem Poem', and its 40 companion poems are pretty much all about love. And so we pass the microphone to Davies.

If you were expecting Davies to make a sombre and restrained meditation on the nature of love, then look elsewhere. ‘Totem Poem' announces its intentions from the very first stanzas with the exuberant and almost Biblical imagery of the sky erupting ‘in the hail of its libation' as Davies and his lover sensuously enter the gap into love with ‘wet-thighed surrender'. Then there is the forthright playfulness of

The monkey swung between our arms and said I am, hooray,

the monkey of all events, the great gibbon of convergences.

(‘Totem Poem')

Such tones and motifs recur throughout the poem's length as Davies and his lover see out their days in the timeless daze and languor of love… and sweet lovin'.

On this journey, they are accompanied by a variety of spirit guide-like creatures. But the facts of the mundane remain. Here is a city where ‘The air / fitted like a glove two sizes too small and too many / singers sang the banal'. There is a rusting car near Yass where the lovers sleep, shivering with sickness.

Circumnavigating all these elements are death and the dwindling measure of time between it and life. Add to this the temporal and spatial immensity of the physical universe into which all living beings enter, and the question then becomes 'how to love (and what is love) in the context of this pending nothingness and this infinite space?'. The seeming timelessness of love falters. Yet Davies proclaims:

And the fact that the wind howled every canyon

(those facts again, like bones) into nothingness meant nothing,

since love we came to understand was held

in life just as the world was held in time.

He also understands that:

… To grasp the eternal

and the ravenously brief we had to learn

to begin to come terms with imperfection.

Thus he and his lover move towards some sort of salvation, albeit an imperfect one. In this state, the world and its decay inhabit them, and they, intimately, sensually, inhabit it. In this state, each moment is impregnated with tenderness and wonder.

And so we come to part two of the book, ’40 Love poems'. Rarely have I seen a book so stylistically divided. Whereas the 270 odd lines of the aptly titled ‘Totem Poem' are almost stream of conscience-style exuberance — playful, sexual, shamanistic — Davies's ’40 Love Poems' are an exercise in controlled quatrains, each poem composed of three stanzas with an ABCB rhyme pattern repeated throughout most.

Unfortunately, this formulaic approach to form is somewhat reflected in content. Davies does not truly develop from the ambitious ‘Totem Poem'. For the most part his love poems, some of which rhyme and flow better than others, are snapshots recounted in a language which, while tender, flounders upon certain images, such as when he compares the glow of his lover's cheeks to that of a lantern, or when he notes the lovers floating in a river with their ‘midday blisses' and the sun blessing their ‘watery kisses'. It is in ‘(Blade)', ‘(Shudder)', ‘(Bearing)' and ‘(Nine Hours)', Davies's knack for incisive metaphoric observation re-emerges. ‘(Nine Hours)', a definite highlight among its 39 brothers and sisters, is concise portraiture, as he conjures up the image of an empty Los Angeles (‘Everyone's off making films today') and combines this with a smart metaphor involving travel, love and flight-paths.

All right, I'm probably being a bit harsh. There are other highlights that display Davies's intelligence, sensitivity and poetic eye. But I want to know, where is the conflict? Where is the doubt? Call me cynical, but having emerged from a previous relationship and its consequences, it strikes me that love is both incredibly complex and incredibly personal. What haunts me less and less now are particular moments of hurt, pain and happiness. A poem such as Robert Adamson's ‘Flannel flowers for Juno', by contrast, takes us into the midst of such emotional turmoil, the aftermath of a terrible event: ‘I can't ask you for forgiveness. / Words aren't part of this landscape.'

How can this depth of feeling be gleaned through statements such as Davies's ‘Her nakedness is all'? I agree, when someone is in front of you, the horizon slips away. But beyond that there is the real — and how, exactly, does love relate to this, beyond the metaphoric? Where are those elements that even love cannot reconcile? Where are the lovers' quarrels? Where is the emotional and linguistic complexity of learning how to say ‘I love you'? Somehow, most of these poems seem too easy, almost as though, having completed the psycho-sexual journey through death, time and love that was ‘Totem Poem', Davies feels he is able tell us, in poetic terms, what to think and feel.

Poetry and poetic language do not in themselves offer any particular connection to the universal, even in rhyme. Indeed, the idea of poetry as higher-language, as privileged connection to Truth, is problematic, if not archaic (as is the idea of truth with a capital T). An inquisitive and detailed exploration of the sites of conflict located in the particular is what foregrounds language as an equivocal entity by which one can hope to inhabit and imbibe an equivocal world.

Davies understands this. Take, for example, the poised and prosaic ‘North Coast Bushfires' (from The Best Australian Poems 2003) where a description of driving at the edge of fatigue through a bush-fire ravaged day conjures up a stark image of mortality: ‘Then lightning / lit up that tree which said: ‘I have / grown into a god.' In poems such as these, Davies demonstrates his ability to counterbalance the visionary qualities of ‘Totem Poem' with a down-to-earth eye for the every-day, a balance that draws him towards the enticing precision of a poet like Jennifer Maiden, to whom I shall leave the last words:

… I think

only a small portion of the brain

has capacity to learn the fact of death.

The rest

of it still expects another conversation.

– Jennifer Maiden, 'Still-Life: Jack-in-the-Box with Moonstones', Mines (Paperbark Press, 1999)