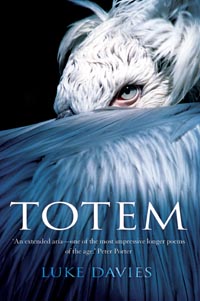

Totem by Luke Davies

Totem by Luke Davies

Allen and Unwin, 2004

The efficacy and strength of Luke Davies' Totem lie in its drawing on a long familiar tradition of mythological narratives as a vehicle for romantic verse-tellers – from Publius Ovidius Naso (known to us as Ovid), to Giovanni Boccaccio, to John Milton. Davies' tastes are eclectic; he even tries a poem in Jamaican English, such as it is generally recognised in reggae songs, in one in the series entitled '40 Love Poems' following his 'Totem Poem'.

Unlike the strict styles followed by these predecessors, Davies brings to his work a free verse-style punctuated with refrains, such as: 'In the yellow time of', 'In the blue time of', 'A practised ear', 'Oh my most girl of light'. He also repeats words, such as, 'fields', 'sky', 'memory', 'time'.

These refrains, in a sense paying homage to that poetic inheritance of Latin and English verse-makers and all lyrical song-writers, re-create in Davies' poems' the insistence on form, as well as on romantic and mythological themes, for effect. These strike me, in their progression, as the sorts of refrains that are more common in Norwegian folk tales, where choruses imbue narrative with an ominous strain of music accompanying anthropomorphism. There, bears, transformed by night as men, become princes, more often than not destined to live happily ever after, who comfort their trusting brides-to-be with, for example, 'You can sit upon my back, and I shall carry you there'. Davies patiently shows us the route of his seductive journey, like that white bear, in his 'Totem Poem':

I have migrated through Carpathians of sorrow

to myself heaped happy in the corner there.

[p. 7]

He makes you want to fall in love, v-e-r-y slowly – to be as 'bees plump with syrup' or 'lions glutted with poetry'. In these full, intoxicating moments, time is expansive and measurable, yet can offer no precision to human feeling. As a subtle study of love and time, 'Totem Poem' offers love as we would have it – falling in love forever. Davies describes what it could mean to seek this timelessness by pointing to all that has the ability to exhibit flux and inhabit it. The world in time and how we measure that, through light, stand as his 'medium'. A coming to terms with this results in a necessary transformation.

…

To us the photon spread through space

in studious propagation. In an ocean the waves

had water to ride on, and sound waves fought their way

through air. But light was the medium itself.

Thousands of birds, the tiniest birds, adorned your hair.

[p. 17]…

Velocity wound down. We all relaxed.

Even the tetchiest rabbit was engrossed. Even the ash horizon

budded and cornflowers flared. Then what I knew

to be the case was death has no velocity.[p. 20]

…

Oh my most girl of light who, astonished, accepts:

the curve of all around us pulled us here &

everything rode on stretching space. To grasp the eternal

and the ravenously brief we had to learn

to begin to come to terms with imperfection.[p. 23]

The wealth of Davies' approach is buoyed up by the smoothness with which he incorporates himself into this ever-expanding love-world, so large it must be drawn as mythic and, by including himself, draws him into mythic propositions too.

At night inside his eyelids in the heart of the maze

the Minotaur kept counsel with the void, singing Clearly clearly the deep

forces of the universe are hope and electricity. I was the only human

for dreams and dreams around. In there with him

one dream inside another.[p. 35]

'Totem Poem' is charged with the first throes of love and rendezvous to rekindle first moments. It bends to the totemic and worshipful. '40 Love Poems' focuses on the companion to this flight, a gravity (in the chief senses of the word) – sobriety, gravity feed, the attractive force of bodies to the earth's centre. I take these poems as expressions of what it might mean to fall in love with any thing to which you become attached, to the point of feeling that your existence depends on it and its existence on you. '40 Love Poems' describes the gravity of sustaining such a high-maintenance relationship and the consequences of partings and yearnings, the effort of renewal, especially so when the two lovers are in isolation, separated by choice or accident from each other. It leads to a happiness where you may become in love with love itself. Here, even the landscape, the world as an act of love, the place where love is enacted must, by necessary participation, become and remain part of the picture of the self-in-love. In my reading of the book, I'd say that the parenthetical titles in ‘40 Love Poems' complement the idea of the aftermath of affections. That is, the previous life continues to qualify the present one, attached to it, as it were, ‘in parenthesis' – all of these titles appearing from the body of 'Totem Poem'.

Idea that earth crunches and body repairs

Is idea conceived in love.

Impatience is the only sin.((Shudder), p. 49)

Love is when green turns to silver

In the last light of day.

We barely knew each other then and yet

The frogs croaked that hypnotic lullabye((Horizon), p. 51)

And only the bird is the witness,

Its long tail trailing colours through the air.

And we are so hungry we are speechless

And you say Stop we will hold each other here.('(Blade)', p. 53)

After the timeless, high moments of 'Totem Poem' in '40 Love Poems', time in the aftermath of first-love is a threat. Now, the thought of this is occupied best by that which can fully afford abstract adoration, poetry itself.

And those walks come to nothing if the taste

Of you is elsewhere, the future for instance,

Or Switzerland, where the hell is that?

Nothing gets right in Love because

Of Time, and Motion; poetry touches that.('(Hell)', p. 73)

Readers will also find that they have fallen for Davies' gravity as well as his flight. This seems inevitable because the strongest point of his style is the ease with which he blends the personal and specific into the large scheme of things as he sees it. He reminds us that the apparently futile desire to rekindle love's high points (such as we can pin them down) have a place in the greater scheme of a world-in-love: 'All mammals myth, pliant, love-haunted' ('(Slide)'). Even the unknowable is seen to be known; the world-before as well as the world-after the recognition of love has the capacity to be Edenic.

Oh to lie upon her

Her nakedness is all

I simply orchestrated

That horizontal fallAnd had no wrong intentions

And cared about no tree

I simply lay with her

And she with me.It is all Chinese whispers

It all gets told askew

I simply kissed the lips

That kissed the apple dew.('(Adam)', p. 75)