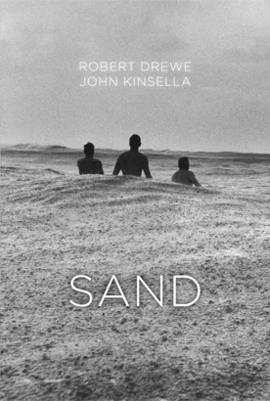

Sand by Robert Drewe and John Kinsella

Sand by Robert Drewe and John Kinsella

Fremantle Press, 2010

Sand is a substance which suggests abundant contradictions. Abundance and scarcity is one; others are leisure and hardship, isolation and revelry, and most starkly the infinitely small and the infinite. Yet, it is rarely held up as something sacred. It is not often treasured for its feel and its ubiquity. While not a paean, Sand, a collection of poetry and prose by John Kinsella and prose by Robert Drewe, does explore this element as a condition of place, in this instance Western Australia, and place as a condition of experience and memory. As such, place in this collection is not a passive subject. It is something constructed through artistic engagement.

Overwhelmingly, Kinsella’s work finds place not as something prescribed by borders but where those borders meet. In the poems, fragments of memoir and verse play, mingling is referred to time and again. Water mingles with the land and vice versa. The sea mingles with the river. Fish and sea birds mingle in the drama of nature, children mingle for games or fights, bodies mingle. There are jetties, where the solid makes a final reach into liquid, and when in the water the last border, our selves, dissolve: “the river fed us / ear, nose and throat infections, / mixed its fluid with our fluids.” (from ‘Learning to Swim’). Instability is, for want of a better term, the nature of place.

The first poem ‘The Dream Of’ expresses this intersection in both content and form. Kinsella writes that he “woke believing [he’d] been living someone else’s life.” This unstable self then segues into a (false) recollection of place:

A dead end becomes a creek

that sources water out of paperbarks,

the roots of marris and banksia

remembered only as street names.

The landscape melds into language. Water runs from the trees to the creek. By attributing the perspective to another, the viewing does not assign the moment to a self. It extends out. The voice itself mingles.

Such a mentality is most fully realised in ‘Perth Poem’, an 18 page poem which sprawls like its namesake. Again, its subject matter and delivery create an even more shifting sense of the West Australian capital. It starts, like many of the poems, with water, namely a river. For most people in this city, sand implies water either by proximity or scarcity. From the river, we are at a school oval with “mocking” and “lean” white lines, which are themselves a part of this intersection, literally in the sense of lines, and also symbolically of chemicals on grass. It is also the places where “church and state dissolve.”

From this point we continue to encounter a constant distention which does not privilege one feature over another. From the line quoted above, the poem continues thus:

the temple or meeting house next to the petrol station,

or near traffic lights: the odds are high,

like car wrecks in front yards

or high maintenance European gardens

The reader is caught in this ebb without the resolution of some specified meaning. The city’s sense comes from the experience of the reading itself, the images always deviating off. The one idée fixe is the word “branch”, which announces the sudden shifts. For example, “Branch: powerlines, those sails strung-up / over the river, as if a meditative religion”. While the word recurs, its use undoes the structure, pushing it ever on.

Nor is the poem resolved in its syntax. It is built mostly around phrases and participle and subordinate clauses – textual asides. Whether this device turns language on its head is debatable. More stirring is how Kinsella has brought that instability down to the linguistic level. This review abides by the rules that there is a point to be made and a syntax to do so. By way of contrast, ‘Perth Poem’ strolls off – a sun-baked flâneur – endlessly open, one clause implying another, to the elision marks, its natural end.

Kinsella’s work is rich in other themes. The above interpretation can overshadow the other layers of the poems which lyrically explore memory and place. The approach can also overlook the sheer exuberance of the language in a poem like ‘River, Bird, City … inland’ which rolls around on its lines. This poem also shows how Kinsella doesn’t shy from the uncomfortable realities of Australia’s colonial heritage, a heritage which is also part of the experience of place. Racial slurs are a part of the linguistic reality. Western Australia is not all cormorants, sunlight and dust.

These political realities are more deeply explored in ‘Signature at Ludlow: a verse-play of transliterated voices for radio’. The play partly deals with Kinsella’s ancestor signing a petition to pardon someone who murdered an Aboriginal man. Memory is not all comfortable vistas either. For Kinsella that colonial reality is expressed as part of the family past. In the same piece he also recounts the violent treatment of a young Nyungar man by police officers.

in Fremantle I watched officers

throw a young Nyungar bloke

back and forth between them

ring-a-ring-rosie

until he was as limp as a rag,

A powerful indictment, yet, his sympathies open up a great many questions about representation. I don’t doubt the authenticity of experience or intent. However, is that brutality his to recount? That such dichotomy is conceivable suggests there is a limit to this mingling. Our body politic is not as fluid as our bodies.

So how does Robert Drewe intersect in all this? Formally, his prose connects with Kinsella’s poetry and prose. Thematically, we expect there to be some overlap since both writers grew up in Western Australia. However, the deeper connection is in how they diverge in approach. Ultimately, what Kinsella leads to is some type of poetic thick description. He strives for the quiddity of place, not its essence. Drewe, on the other hand, comes at place as something already gone.

Drewe does a lot of remembering in the texts collected in Sand, texts taken from his memoirs, novels and collections. The memories are either his or those of his characters. He euphorically recounts sand, stones, grass and skin with a palpable texture. Take for example this passage from ‘Buffalo Sunday’: “In that drowsy quarter-hour I somehow realised that this sandy, windy place where even the grass had an individual character, was where I was from. It was the first backdrop that I remember having meaning for me. It felt right.” For most people, lying on the titular grass brings rashes.

His touch also works on the seemingly grotesque. In ‘The Sand People’, taken from The Shark Net, he describes with envy the children who “peeled sheets of skin from their shoulders and passed them around for comparison”. He makes the casual behaviour sacred, as though inviting readers into some secret rite. Even the way he writes about the preoccupations of kids, their digging tunnels in yellow sand and urinating on moss, has a way of elevating the suburban to the significant.

Where this differs from Kinsella is how the focus on memory keeps the place at distance. Place is somewhere you cannot easily return. It’s something which comes to us in this intense recollection of experience. Kinsella branches out. Drewe is borrowing in, much like his young self in the yellow sand. This difference is most stark in what sand can represent. In the piece ‘Gero Dero’, Kinsella associates sand with ostracism, his own and others. He shows in the same piece that sand is something people strive to remove. Drewe, however, seems to long for the sand. No wonder the young Drewe in ‘The Sand People’ tried to plug a hole of pouring sand, living in fear that it would one day pop.