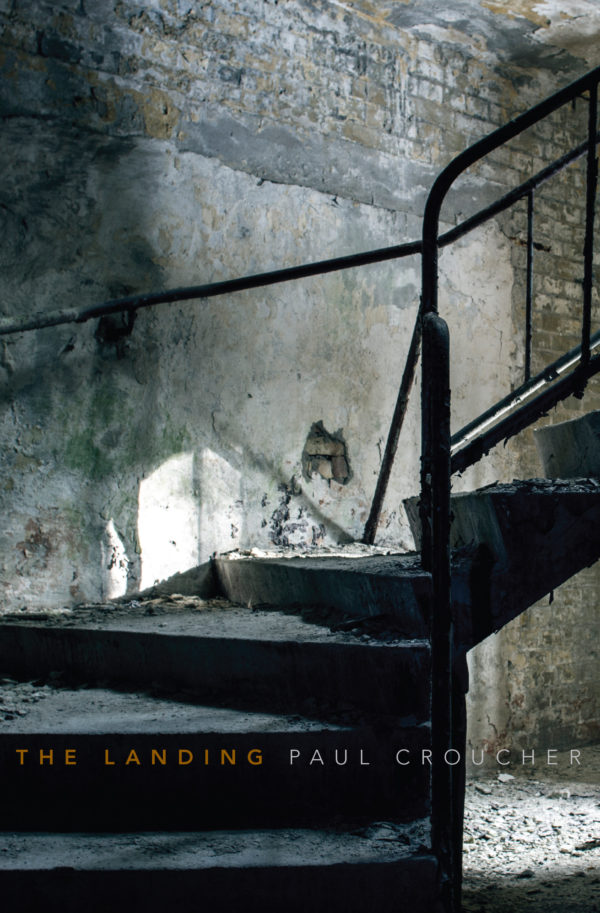

The Landing by Paul Croucher

Transit Lounge, 2017

While Paul Croucher has previously published A History of Buddhism in Australia 1848-1988, this is his first poetry collection. Embedded within the poet’s attention to nature is a Buddhist understanding of suffering as a necessary part of existence and at times his spiritual beliefs are expressed explicitly. In ‘Theravadin’ the speaker asks his ‘Ajahn’ (teacher) why he has been reincarnated and is told: ‘Not enough suffering / the first time’. The notion of ‘samsara’ – the cycle of birth and death to which non-enlightened beings are subjected – is reiterated in ‘After All’, a poem in which a courtesan states, ‘there’s / no future, / but there’s / no / end to it’. At first the courtesan’s attitude seems almost despondent, but this is undermined by the speaker’s description of an idyllic landscape:

In the sutra the courtesan says to Sudhana there’s no future, but there’s no end to it, in the foothills of Nepal, in the clouds of the countless rhododendrons.

Croucher’s tight enjambment – the poem consists of a single sentence spaced over eight couplets and a monostich – necessitates a pause after every couple of words. The pacing reinforces the Buddhist mindfulness and mystical themes of the book. That is, the poet’s spiritually informed comprehension of impermanence is both thematically and formally visible.

‘On a Bus Somewhere to the West of Minneapolis’, one of several poems which make reference to Croucher’s poetic influences, begins with the lines, ‘with a cask of wine / and a lover of Lorine / Niedecker’. At his best, Croucher, like Niedecker, demonstrates imagistic precision while maintaining a personal tone. Both poets are also very much concerned with the natural world and rural life, or at least the non-urban aspects of suburban life. For example, the opening couplets of ‘A Solitary Garden in the Seventies’:

Broad beans

in the winter sun.

The sounds of trucks

in the breeze.

Meghan O’Rourke and A E Stallings, in a 2004 review of Niedecker’s Collected Works, identify some of its main features, three of which show revealing relationships with Croucher’s poetics. These are ‘a chariness with syllables … the ‘I’ of the poet condensed out of existence … and a refusal to sentimentalize’, all of which are displayed in one of Niedecker’s untitled poems:

Popcorn-can cover

screwed to the wall

over a hole

so the cold

can’t mouse in

Niedecker, like Croucher, writes with a certain laconicism. In Niedecker’s words, ‘certain words of a sentence – prepositions, connectives, pronouns – belong up toward full consciousness, while strange and unused words appear only in [one’s] subconscious.’ In other words, her ‘chariness with syllables’ results from a prioritising of words she deems as expressive of something subliminal – ‘laurel in muskeg / Linnaeus’ twinflower’, or ‘mud squash / willow leaves’ (‘Wintergreen Ridge’) – over words whose principal function is grammatical. This is not to say that her poems are ungrammatical, rather there is a hierarchy with regards to the types of words she is likely to edit out.

Whereas Niedecker’s poems are syntactically economical, Croucher’s ‘chariness’ manifests in heavily enjambed verse with very few words per line. Moreover, his poems do not always conform to the rules of grammar and tend to be fairly quotidian – no precedence is given to unusual words. Croucher’s ungrammaticality is a technique which seems to evoke both stillness and a spiritual incompleteness – a sense that everything is temporary and therefore trivial. ‘Zen Keys’, for example, is a poem that consists of only two dependent clauses:

Recalling how Thich Nhat Hanh lost his temper with Frank, who had lost his keys.

In contrast to Niedecker, Croucher’s ‘I’ is not ‘condensed out of existence’ per se, rather the significance of ‘I’ is undermined by the spiritual tone of the book. For example, ‘A Proceeding’ from the ‘Arboreal’ sequence, is ostensibly about a mundane situation. On the surface, it deals with the speaker’s future lack of comfort, but there is also an implied reverence for nature:

A spring wind’s snapped the branch of the gum tree which in summer was to shade my room.

At times The Landing shows comparatively less of a ‘refusal to sentimentalize’:

The ordinary things, like a water buffalo with a dozen birds on its back.

His focus on nature and the absence of a verb gives the poem a haiku-like quality, a sense of stillness suggestive of transcendence. However, the way in which the presence of the speaker is implied is a little self-conscious. That is, the image of the water buffalo is intellectualised, albeit very slightly, by the inclusion of the initial four words, ‘The ordinary / things, like’, whose gratuity, although slight, make the poem sound, if not faintly sentimental, at least un-Niedeckeresque.

Perhaps the most Niedeckeresque feature of Croucher’s poetics is his application of rhyme. Just as Niedecker frequently uses one-off occurrences of rhyme in her short poems – ‘My friend tree / I sawed you down / but I must attend / an older friend / the sun’ – Croucher, in the second section of his extended poem ‘The High Country’, rhymes only the first two lines of the first tercet:

As the embers and the ambers of the morning become one with an acid clarity, we’ve of a sudden the immanence of cattlemen

Once again Croucher’s heavily enjambed free verse requests a certain mindfulness of the reader. The poet’s newfound ‘immanence’ is something that he supposes is possessed by cattlemen because of the time they spend with animals in nature. The speaker’s epiphany, therefore, is based on a projection of his own philosophical beliefs and is perhaps a romanticisation of non-urban life. Whether or not the speaker’s epiphany is nothing but a temporary delusion is perhaps irrelevant. When the speaker in ‘Libre’, on the other hand, supposes that plants are sentient this seems somewhat incongruous with the animistic voice of the book:

Peach blossoms blown across the field like snow. Each knowing, since the beginning of time, where they will land.

The presence of the poet, despite the absence of the first-person pronoun, is perhaps too forceful. His anthropomorphisation of peach blossoms does not enhance the spiritual or immaterial qualities of nature, rather it does the opposite, it invalidates them. The romanticised ending jeopardises the impact of the first two couplets, which by themselves have the potential to be autotelic and reminiscent of William Carlos Williams.

Williams’ ‘Red Wheelbarrow’ happens to be the namesake of Croucher’s recently-closed bookshop in Brunswick, Victoria and The Landing, although at times less linguistically precise, is recurrently redolent of his work – ‘Rust / in a basin / left out / in / the rain’ (‘Rust’). Moreover, Williams’ famous tenet ‘no ideas but in things’ is quoted in ‘The High Country’. Following his epiphanic encounter with immanence, the speaker goes on to admit that writing about spiritual occurrences is a form of unnecessary intellectualisation. He defines his cattlemen-like capability as something

in which there’s no Baudelaire, no Satan, no cosmic feud. No abstractions in the log book. Only gratitude.

The ‘no’ anaphora combined with end-stops stand out against the other severely enjambed lines and this technique develops into something of a motif:

No coins. No prayers. No fountains. (‘Chinese Pastoral’)

No wing. No prayer. (‘A Dream of the View From the Monastery On Khao Laem Dam’)

No positioning. No posturing. (‘A Drink With Eric’)

The occurrence of profound gratitude, according to the speaker in ‘The High Country’, is a non-cerebral experience analogous to Williams’ theory of poetics, which Croucher interprets from a Buddhist perspective to imply that what exists only in one’s head is meaningless:

And although in the clear light this might be an idea it’s one that’s closer to having no ideas but in things. Just being here. […] we’re nothing if not in the flow of things.