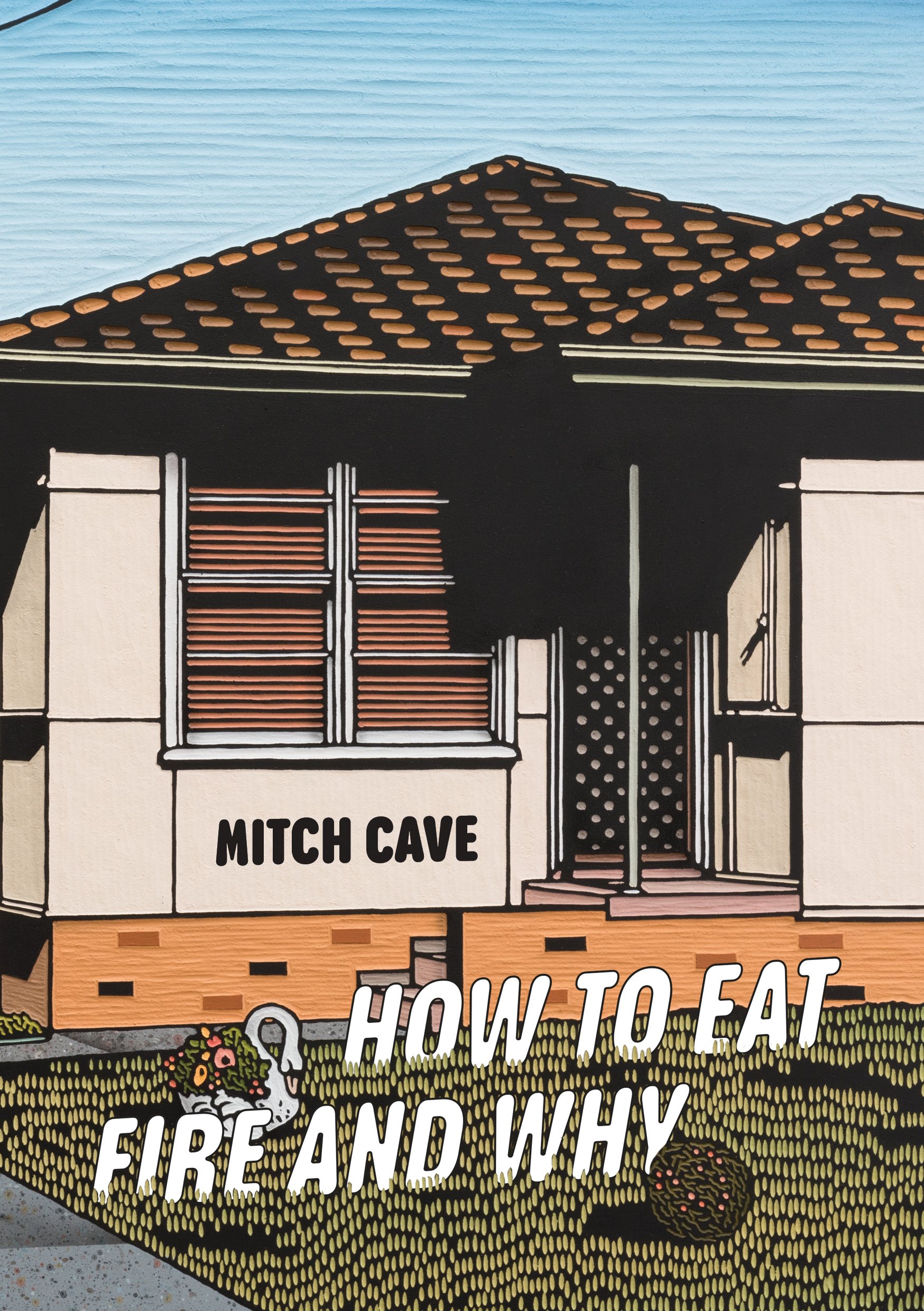

How to Eat Fire and Why by Mitch Cave

How to Eat Fire and Why by Mitch Cave

Rabbit Poets Series, 2022

No Camelias by Rebecca Cheers

Rabbit Poets Series, 2022

Your house burns down. You reconstruct yourself in elements. It’s how you emerge into a new world of coherence, through gathering and articulating the fragments. Your body merges with others: you are fluid and combustible at once. You dispense with time and exist in multiple layers of space. You evolve from the fire. A final resolution remains out of reach.

This is Mitch Cave, taking his burnt house even further apart; atomising the remains and releasing them into the elements within which the charred and splintered carapace and its dispersed particles attempt to find one another, recover, and cohere. His collection is aswirl with debris; it floats, never quite settles, instead accumulating over the pages to produce an upsurge of energy and luminosity.

Where do you house yourself after such loss? What has happened within the self? Here we have an internalisation and extension of the event all at once: its shifting and embodied immanence. The body seeks others and at the same time puts out its own its parameters:

hold raw flesh in one hand and signal small fires to burn around my body (‘Splendid is the sun orbiting around you’, 5)

The heat is not quite at arm’s length and gives off in turn an uneasy sense of ongoing decomposition and liminal uncertainty: where and who to live with or within?

Cave ironically observes:

we never quite decided on a vacancy we will next inhabit (‘How i got home from noosa last night’, 2)

He is unsettled. References to fire and burning are everywhere, only now they are potentially life-threatening triggers. Barbecues become a source of fear. Yet alongside this comes irony and resilience. And this is evident in the young poet in how he makes himself immediately present, singing at the crash scene and letting the fire, flame, and burning collocate with its salient components; other humours, other elements.

His collection is grouped and presented in those old-school humours or elements: the first of these is Air, the space for combustion (or vanishing), which Earth can put out, or literally ground it, as “red slides down the centre / of his cracked arrow mouth” (‘Observations from the balcony, barmore street, 18). Water and Fire are positioned as paradoxical yet apposite. At least, this is how the book appears to track and dip, before rising through a sustained crescendo to a succession of fire points on pages which assume a contoured, and at times contorted, face.

Air is combustible shockwaves, and Earth may attempt to ground these, and struggle with absorbing their aftermath. The Earth poem that stands out is ‘Panic room at a Party’: halfway through the section it disorientates and forces the reader to slow down with its suddenly irregular punctuation (23). What to do with a few disjointed, ad hoc, strobe lit sheets of aphasia? Run, crouch, hide, reconstruct, repeat. After that “the garden’s absolution” hands it over to the plants to take over and discuss this predicament (‘The garden’s absolution’, 24). A palm frond telling a flower: “no-one is going to make it out of here alive, that’s a given” (24). Earth is something that may be grounding, but also an element the poet must leave.

Water comes next. It absorbs and liquefies bodies to suit its own protean purposes: neither the sublime Venus (as a boy) nor a plastic cup of sugary slush avoid its processes. “The ocean is looking at us,” maybe willing us to keep changing, or as part of a shared construct involving ebb and flow. Tidal resonance and return are tropes that become more evident as the collection starts to show an accumulation of previously withheld energy and power, after having started in its overtly fragmented, dispersed and almost scattered way. ‘Supermoon king tides, noosa heads’ ends with such an instance, where wordplay gives way to something more powerful, luminous, and strange – akin to Lars von Trier’s melancholic musings:

before i go to sleep i lift a bucket over my fallible remains i tilt i pour fire over my body good night (41)

In ‘swan song,’ the poet gathers shards from a nameless “apocalypse,” nameless apart from the man who is absent, whose invisibility forms another layer of elements to get through:

carrying nightfall in my palms i begin to remind myself of your skull’s absence i look on as a lighthouse begins to burn (43)

Another building is on fire, oceanic, liminal but also literal: the light it gives when intact, the light it emits when falling apart, the lightness of its substance.

Following these aqueous bodies is Fire. This section begins with the poem ‘if we were burning,’ with smoke, breathing, asbestos – words separated like beings taking evasive action (46). Throughout these final poems, the narrator seems to be articulating the ends of his unrest, as if seeking some kind of a place or to be in some way reconciled with the elements:

do you have fire in your bathtub grieve in water you whisper something about a phobia of burning (‘I live with you’, 48)

Fire is the intruder, fire confined in a vessel for water, which when released becomes a repository for mourning. Fire insidious; slipping into intimate spaces, sliding in on the slightest of sounds, something that leaves a mark no telling can erase.

No surprise that this final section is marked by the prevalence of dreams, the presence of fire in landscape and in the bodies that traverse the dreamscape, such as “a man wandering in a forest / smoke exiting his shoulder blades” like an unquiet ghost from a nameless ritual within the subconscious (‘Nightmares or, side effects may include’, 51). There are tropes of falling birds in another evocation of melancholia and apocalypse. “Murky gold” shines through ashen skin, goldfinches appear for an instant of uncertain satori, tensile flashes of life in colours ascribed to burning and its aftermath (51).

Everything relies on heat, and although fire has its season, when it comes it is everywhere: “there was ash in my coffee yesterday […] wind shapeshifts into flame and we are all on fire” (‘Bushfire season’, 54). Our sensory apparatus is supported by warning alarms, but the animals fare little better, even when set free, “the way their bodies / bend and twist in glow” (‘Memory’, 53). Fire consumes everything in order of how elements, atoms, molecules, and substances align. It becomes the stuff of memory, dreamscape, nightmare. It is both immanence and evocation.

Cave’s final poem in this astonishing collection, ‘You, your light,’ is also in some way redemptive: “i know / how to breathe like lanterns / do,” he quietly claims, so maybe here the eating of fire is explained (‘You, your light’, 56)? Is this a form of transmigration, transformation, or evolution that has come once the house of his being, his carapace has burned itself to death? What does Gilgamesh say about this? Burn your house down and look for life, build for disaster up ahead. The poet appears to be preparing for something at once all too recognisable but also not entirely reckoned. As the ‘Fire Sermon’ from Buddhist theology may be paraphrased: everything is on fire, but a pathway to liberation can be made out once this is realised, accepted, and put into perspective (Christmas Humphreys, ed. The Wisdom of Buddhism, 1987: 45). It is to Cave’s credit how he takes on the immensity of this task.