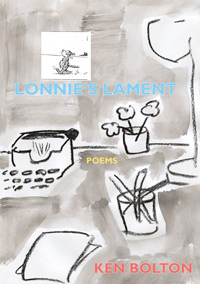

Lonnie’s Lament: Towards a History of the Vanishing Present by ken Bolton

Wakefield Publishing, 2017

Ken Bolton’s most recent collection expresses an intense sociability, co-mingling personal and communal memory to create poetry that draws on moments of apparent ordinariness, and ever so subtly transforms them into lines of understated enchantment. The poems are typically written for and about people close to and loved by the poet, reflecting a sense of togetherness tinged with an anxiety over the aspects of everyday life that separate as well as connect. Shifting between recognition and anonymity, conscious of finitude and erasure, they comprise a form of metis, or art of working things out that previous generations (indeed, ages) once had, and whose humour mass society seems to have lost.

Lonnie’s Lament opens with a long poem dedicated to the memory of Philip Whalen, referencing the San Francisco Renaissance and Zen Buddhist poet from ’67, crossing the dateline with its concomitant ambiguities regarding time and imagination. The poem creates and negotiates a thicket of names and years, working things out, with preoccupations and divagations cut short, looping back, seemingly in search of, yet evading an ending. As it circles with near repeats and recurrences, the poem creates an awareness regarding history and the ambiguity as to where it starts and who it includes: the folly of trying to pin down what demands to be lived: ‘Dreaming?) / My body turning, in some future’. Throughout the volume Bolton questions the dates he gives, just as he consistently reaffirms the names of his friends, bringing them closer, contrasting their reality and immanence with the unreliability of time. This process of questioning and reaffirming juxtaposes intimate and historical memories with dates and figures open to doubt: ‘A century / of interesting Times. More. Beginning when? / 1871? 1789?’ Revolutions consigned to the uncertainties of the disappeared past leave traces that are discernible in the seemingly unrelated present, through what Whalen’s contemporary, Charles Olson, referred to as a ‘syntax of apposition’. Bolton’s stream of thought continues with: ‘Anna, Lila // Sal // “Omaha” – the tugs – // now that name always makes me think / of the beach landing at Normandy.’ These cryptic yet clearly placed connections present space and time as the elusive elements that comprise the overall tapestry of interlinked lives, the cast of the overall shadow play.

The proverbial interesting times are not immediately apparent in some of the calmer stretches and sensibilities evident. For instance, in the poem ‘Train Tripping’: ‘thinking // of Pam & Jane & Cath & / Pam’s question – as to what Cath // does alone on Bruny & my / explanation: fishing and hiking around, // dinner with Lorraine & Ian / & friends up in town // & Pam and Jane’s life in Blackheath: / what they do’. This mustering comes without melodrama or self-importance: naming is creating, or more to the point reaffirming the existence of who and what one loves. The familiar comes with its attendant angst, and with his need to pull these human strands together, perhaps the poet is telling us that domesticity takes place just so slightly out of one’s comfort zone, or at least the immediately known environment. ‘I play some Dave Holland / move around the house / / doing things, picking up, / tidying, straightening – / / inside, outside – time / like an element around me’. Hints of the proverbial noonday demon are offset by a gentle irony, just outside recognisable surrounds, ‘including the street / where I almost fancy / I can see the restaurant / I ate in for years / where they threw me out once / asleep before / my raznichi’. Bolton adds with a touch of mischief : ‘I was aghast. / How could they?’

Further out, literally overseas, at apparently random meeting points, the sense of estrangement amplifies and demands more solidity in response from places experienced. Given that a cup of coffee can become ‘something different / in Adelaide: / the price of an air ticket. A / view of the blue thru pines’, the narrator of the travel sketches that fill out the middle of the book states: ‘I never go to Asia. / It is not a firm enough idea.’ Direct or disingenuous? Possibly both. Considering the extremes of terrestrial limitation gives rise to some semantic wordplay on furniture and geological fissures along with a gentle mockery of human delusion of control: ‘can large aesthetic / continental shelves co-exist, / in detente? They / can if I say so.’ Make things work or leave them to their own devices: the results are likely to be equally inconsequential. An essential and delightful part of this book is that it converses and jokes and refuses to take itself too seriously: its underlying melancholia is moderated if not by outright mirth then a tone midway between levity and the titular lament. As with Whalen, whose self-effacement and humour Bolton shares, this is poetry which can be found in everyday life, and literally everywhere.

Through these understated operations, Bolton recreates existence in the close company of friends, fellow poets and self-objects. Like Whalen, whose self-portraits ‘from another direction’, find elements of affinity here, Bolton puts forward a series of vignettes, not entirely settled and at times almost intentionally unsure and displaced, yet which indicate an essentially optimistic, nuanced and multi-faceted outlook on this uncertain age. Lonnie’s Lament decries enclosure and conformity, while celebrating the quiet joy of close and loving connections, adding another impressive and humanistic work to its maker’s extensive and generous oeuvre.