Argosy by Bella Li

Vagabond Press, 2017

Bella Li’s Argosy offers readers a book of real adventure: the adventure of form, and a challenge to our sense of what shapes a narrative. This work is fundamentally hybrid: amid short texts and textual sequences that may be termed prose poems, or micro-essays, or short short fictions, Li intersperses works of collage and photography. These visual elements of the work are not supplemental or separate, but are themselves linked to its central narratives. The whole book takes its cues from the collage novels of Max Ernst; his Une semaine de bonté: A Surrealistic Novel in Collage and The Hundred Headless Woman provide the titles for the two sequences presented in Li’s work. At the same time that she draws upon Ernst, however, Li offers significant reconfiguration of surrealistic working methods. Where Ernst accompanied his collage images with captions – producing a text that bears a relation to the contemporary graphic novel – Li offers discrete segments of pure visual narrative, followed by sections of the work in which only text appears. The full-colour reproduction of this work makes for a lush object, which reminds us how central the ability to dwell with pictorial work has been in the history of reading. The interplay between the visual and verbal work provides a dimensionality that would be difficult to achieve through text alone, allowing critique to emerge in the friction between the two. These are works that are informed by postcolonial and feminist thought: they do not provide disquisition upon these topics, but offer instead an imaginative inhabitation of these ways of seeing the world.

In the seven-part sequence, ‘Pérouse, ou, Une semaine de disparations,’ Li generates visual collages from illustrations in old atlases, themselves supplementary texts attached to journals of discovery. The Journal of François de Galaup de La Pérouse is the central text that governs this sequence, and the seabound explorations he led no doubt provide the title Argosy: an argosy is a particular type of ship, a merchant vessel originating in Ragusa or Venice. At the same time, though etymologically unrelated, the title puts the reader in mind of the Argo and its Argonauts. As such, the ancient, mythical quest of the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece is merged with the merchant state of Venice at the European hub of the Silk Road, and then to the latter stages of the age of exploration in which the South Pacific represented a last frontier for those seeking to chart the world’s landmasses.

Li composes three sequences of collage before presenting the reader with the first textual sequence. In these collages, the interplay between human and nonhuman is central. Boats are rendered strange as they carry enormous cargoes of shells: here an inverted gastropod shell stands on its tip, replacing the mast of the ship; there an oared boat is propelled forward by wind in the wing-like sails of oversized, splayed mussel shells. Hovering over one open boat is the grass-thatched roof of a Pacific island fala, while on the stern of another, gigantic flora blooms. The strange birds of strange lands are rendered stranger, as they too are made enormous when compared to the tiny bodies of the explorers and the European houses in which they normally dwell. Such play with gigantism can be seen in the way the unknown – exoticised in the huge, near-naked bodies of men bearing weapons, their heads replaced with seashells and flora, given scale by the trees and clothed men who sit at their feet – loomed large in the minds of explorers such as La Pérouse, and continues to loom large today. Think of the latest iteration of King Kong, its weirdly unlocatable South Pacific site filled with a myriad of strange gigantic creatures: Western culture has not moved beyond this form of exoticisation.

Against these images that, by their embodiment of the strange, answer back to the explorers who recorded them, Li writes two sequences of prose. These works are understated and restrained, occupying the gaze of the explorer who is concerned with cataloguing what he sees. This creation of binaries is evident in the opening text:

This day we sail, dividing the waters from the heavens. I am my own guide, the steerage, the hull. This day by sea, by the sea we lie. Sharp peaks divided, three by two by three. Our man at the helm, broad-shouldered and in love, saying: This but not this. This, but not this. You ford the stream. You move.

The self that is its own guide, its own hull, is set against everything that is not the self in this sequence. Division is the fundamental action of the newcomer as he encounters the new: we don’t need to know what is being catalogued in the words, ‘This, but not this’. It is the world in its entirety.

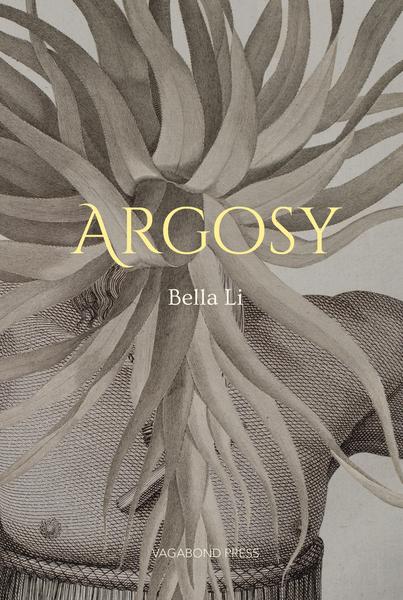

The second half of the book takes the reader to a compendium of stories and images that investigate women. ‘The Hundred Headless Woman’ is reinvented many times, as Li moves through historical, literary and cinematic sources; at the same time she uses her own photography and collage to comment on contemporary visions of femininity. In ‘Eve & Co’ she presents photographs of often run-down urban environments, with the juxtaposition of (headless) illustrations drawn from sewing-packet instructions for women’s clothing. The scale and placement of these women within the city-scapes is both a contrast – their brightly coloured, immaculately illustrated stylish clothes are at odds with the unglamorous environments in which they stand – and a comment on the perceived requirements of womanhood – whether lived headlessly or not. Meanwhile, the final photographic sequence of the book, ‘La ténébreuse’ shows a long-haired woman whose hair, in each configuration, is the centrepiece of the image. Whether she has her back turned or is seen side-on in various settings, her hair replaces her face. This facelessness is a form of anonymity that speaks both to the exceptional women of the text in this sequence, and the many more women who have not risen above their historical anonymity.

Exceptional and anonymous women are brought together in the figure of the famously anonymous Elena Ferrante, subject of the short third part of this sequence. Ferrante’s voice is rendered fragmentary: ‘For instance, in Ischia,’ the poem opens. The voice is by turns in pursuit – ‘Hunting the particularity, the moment, seen so closely from afar. Down the lanes, always in the company of a shadow, a woman, a cleaver’ – and in flight, ‘My sister—a girl then—clear, cleaving to the shadows, and once. Once we ran from house to house in the dark, calling names, falling and our knees grazed.’ The brief text captures the sense of impending violence that is sustained throughout Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels.