Roseland and Boltonia …

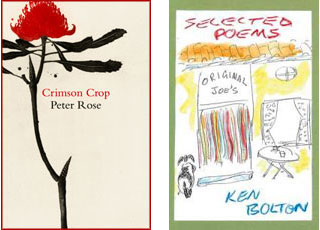

Crimson Crop by Peter Rose

UWA Publishing, 2012

Selected Poems 1975-2010 by Ken Bolton

Shearsman, 2012

The opening poem of Peter Rose’s Crimson Crop – which recently won a Queensland Literary Award – brings together illness, noise, and madness in a powerful vision of human frailty. In that poem, ‘Prelude’, the poet relates seeing a man at the Rome Railway Station banging his head on vending machines, while his countrymen ‘rushed to their trains, / fearful, cashmered, blinkered, / avoiding this glimpse / of what their brother had become’.

This is an uncompromising and disturbing opening, especially from a poet one might associate with urbanity, satire, and wit. But Rose’s poems are not all smooth surfaces. They habitually accommodate comfort and pain; bourgeois pleasures and bodily abjection. This is seen most profoundly in two of the collection’s key poems: the eponymous poem, which ends by bringing together afternoon tea and memories of a war crime; and ‘Morbid Transfers’, an elegy for the poet Bruce Beaver in which Rose recounts witnessing the death of a squash player in a gymnasium.

Rose has always been sensitive to loss and human frailty, as seen in his prize-winning memoir, Rose Boys. The elegiac nature of Rose’s poetry has deepened in Crimson Crop, with the second section being entirely elegiac, either in the sense of offering poems concerned with loss and mortality generally, or poems dedicated to the dead specifically. In addition to the elegy for Beaver, there is an elegy for the poet’s father, ‘Beach Burial’. This poem is freighted with elegiac predecessors: it takes its name from a poem by that great Australian elegist, Kenneth Slessor; it begins with an epigraph from Douglas Dunn, the author of Elegies; and it is dedicated to Craig Sherborne, whose own paternal elegy, ‘Ash Saturday’, also recounts the scattering of a father’s ashes in the ocean. Such attention to literary precedents draws attention to Rose’s poem as intensely stylised. Stylisation is the long-standing problem of elegies, since it might suggest an attenuated relationship with real grief. (‘Where there is leisure for fiction there is little grief’, grumbled Samuel Johnson about Milton’s ‘Lycidas’). But, like the poems it references, ‘Beach Burial’ shows that stylisation and grief are not inimical things. The poem ends on a deeply emotional note, with the poet lamenting the loss of his father as an extension of paternal distance: ‘our fathers are preoccupied, / turn their heads west – even in death’.

Given the elegiac nature of this collection, then, it is not surprising that ‘Loss is everywhere’, as Rose writes in ‘Motes’, one of his superb catalogue poems:

It is the torch song we fail to heed. It is the jazz riff upstairs. It is the costive traffic. It is the portly jogger rounding a lamp-post like a clumsy skiff.

‘Costive’ here might mean sluggish, but it also means constipated, an amusingly inapposite adjective in a poem about loss. The ‘portly jogger’ deepens this unexpected comic turn. But the two images are not accidental, suggesting that whether we are inert or energised, loss is doing its work.

The fusing of the comic and the elegiac can also be found in ‘Fifteen New Poems in the Catullan Rag’, poems that continue the sequence begun in Rose’s second collection, The Catullan Rag, in which the unheroic exigencies of modern life are satirically represented through the terms and style of the Latin poet, Catullus. These new poems in Rose’s ‘Catullan Rag’ continue to satirise the Australian literary scene. The academic Socration, for instance, is advised to ‘stick to existentialism: / he knows all about bad faith’. This neoclassical revision of contemporary literary life is hilariously caustic and it has the sting of the real in it, too. (Rose is, after all, the long-time editor of Australian Book Review).

But the literary life appears in less satirical ways throughout Crimson Crop. It can be seen in the way life and literature intersect in powerful and unpredictable ways: the poet toying with the idea of reading ‘Lord Jim’s / crazy lesson (marked Epiphany in red)’ to a group of schoolboys to whom he has to give a speech; the poet reading Elizabeth Bishop aloud to himself, to the chagrin of a young real-estate viewing couple; and the poet reading Against Nature, of all things, at a local cricket match.

This complex to-and-fro of the mundane and the extra-mundane is undoubtedly one of Rose’s great themes. But the literary life is also seen simply in the special aestheticisation of experience of which Rose is a master. Such aestheticisation occurs in his powerful imagery; his arresting, almost surreal phrases (‘Autopsies of the bungalow’); and in his extraordinary prosody and attention to sound, as seen at the end of ‘Torrens Bells’:

Dusk evacuates a park, leaves a clumsy silhouette, woeful, shivering, staring at the palmy void. Night programs its shadows.

Ken Bolton is, outwardly, very different from Rose. Where Rose’s prosody is contained, Bolton’s is expansive. Where Rose is attracted to implication, Bolton leans towards plain-speaking. Bolton is more likely to evoke Rock ’n’ Roll Animal than Fidelio. But such contrasts have their limits. For a start, while the cities are different, the milieus of both poets are urban or inner-suburban (Melbourne for Rose; Adelaide for Bolton). Bolton, like Rose, also came to his style relatively early. While his Selected Poems covers work from 1975 to 2010, one doesn’t get a strong sense of development (a notion that the habitually sceptical Bolton would probably put in quote marks).