Poems of Masayo Koike, Shuntaro Tanikawa & Rin Ishigaki, Leith Morton, trans.

Poems of Rolando S. Tinio, Jose F. Lacaba & Rio Alma, Robert Nery, trans.

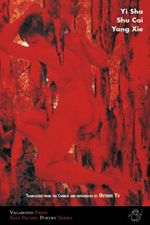

Poems of Yi Sha, Shu Cai & Yang Xie, Ouyang Yu, trans.

Poems of Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan & Nhã Thuyên, Nguyễn Tiên Hoàng, ed.

Vagabond Press, 2013

Vagabond Press has recently issued four attractively presented volumes of poetry from the Asia Pacific region. Each contains the work of three poets and represents China, Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines, respectively.

In the selection from China, Ouyang Yu provides an introduction which is concise, forthright and irreverent, so it should come as no surprise that the three poets he has chosen, Yi Sha (b.1966), Shu Cai (b.1965) and Yang Xie (b.1972) share these characteristics. There is a cool muscularity about these poems. For instance, Shu Cai ‘favours the cleanness of words and images’, Yu writes, ‘a poetry with contemporary rhythms that resonate with his themes of absurdity, of death and of memory.’ His poetry exemplifies the connection between source and form, what Yu calls ‘the centrality of solitary insight’. In ‘Ocean Sea’, the sound from the ocean’s depths and from those of the soul, present a language both perceived and created:

All we can ever do is listen to the sound from the depth Of our selves All that can be forgotten needs to be forgotten As the stars and the earth refuse to be forgotten At the seaside where I sit and watch I seem to see life right through to its other end

In ‘Sunday Free’ there is a transposition of self into nature, as the speaker is ‘full of wings/Inside my house, flying inside the bus.’ Once at the beach:

Over my head, a huge bird is Flying, and I am sitting A bird whose wings have grown Thoughts

Yu mentions the poet’s engagement with the poetry of René Char and Pierre Reverdy, and this cross-fertilisation between French and Chinese poetry is evident in Shu Cai’s making of solitude within the fabric of the poem. ‘Hai Zi Forever’ resonates like Char’s work, while ‘Extreme Autumn’ extends the transnational influence, suggesting Wallace Stevens through its images of autumn as a mirror and a tranquil thinker at the very quick of nature. The superb ‘Absurdity’ delineates heightened desensitization, as the speaker ‘like a poplar by the roadside’ plunges into a world where ‘Cruelty was the greatest reality’.

In regard to Yi Sha, Yu praises his poetry for being ‘accessible, direct, hard-hitting, filled with riveting stories that tell of all facets of modern life’, a view of modern life presented with a mordant and what some might consider masculine detachment. The most successful appear to be family pieces, such as ‘The Battle with the Puppet’, in which furniture blocks and confine the argument within a domestic setting:

i was having a great talk with my father like puppets fighting each other in the mirror of the big standing cabinet an argument which had: an unhappy ending I capsized the table and all

Yi Sha’s poetry generally offers some wry perspectives on its contemporary themes, and his technical ability is at its best in ‘I Wrote Again About My Mother’s Departure’, which has the spare economy of a Balthus nude. But its social observations have their limitations. It’s possible that the poetry may be stronger in Chinese, but its combination of conservativism and sentimentality is conveyed in the locker-room-macho tone of a poem such as ‘My Next Door Neighbour’, which describes gay women: ‘good girls lying fallow/is really a waste.’

Yi Sha’s implicit gender anxiety is also present in the poetry of Yang Xie, who works with the expressionist elements of nausea and the olfactory, elements which are specifically gen-dered. He uses unripe or rotting fruit to good effect in poems such as ‘Rotting’, which works particularly well to create contrast between a ‘purely white, spotless apple’ and the ‘rotten pear …chucked in the bin.‘ In this ‘disgusting poem‘, as the author calls it, mundane decay extends into the world of the city, death, prostitution and the police. This is further explored in ‘The Night Women’. Viscera constructs the poem, where ‘night women … quietly ooze liquids, fishy and oily’:

the night women flood this small city they spread this small city with their peculiar fragrance and let it in this atmosphere rapidly become white apples wrapped in white paper in the bamboo baskets and pears that sit permanently on the trays on the desktop

In other poems, like ‘Something Is Taking Leave’, onomatopoeic effects are worked in to this abject landscape, where sounds of a dripping tap, a ticking clock pour into the body. Underscoring a sensibility that runs through this series, Yang Xie is a highly visual poet, recording sensation in deft strokes of the pen. In ‘A Man Died’, the depiction of an unequal exchange of prestige, wealth and social attitude are portrayed as a painter might:

He stopped me as I was about to go past their BMW Saying he wanted to introduce me to his wife as a poet But the woman’s morning-fog eyes Swept past my face to dwell on The florid rubbish bin behind me Till I said bye in a hurry two minutes subsequently A man died just like that Remembering all those things I can’t help writing this poem

It is possible to imagine ‘the woman’s morning-fog eyes’ as being the initial impetus for the poem: the image is emblematic of a visual expressionist palette, and its confrontational nature is the locus of challenge for the poet.

Turning to the Japanese selection, a visual sensibility predominates, but of a different kind. One is struck by the poems of Rin Ishigaki (1920-2004); as exquisite objects, they balance intellect and sensibility; what she describes in as ‘In the midst of eternity/At the intersection of time and space/The drama of the “everyday” unfolds’ (‘When the Sun Rises on New Year’s Day’). Linguistically brilliant works with a touch of William Carlos Williams in their attention to detail, they address femininity in such gorgeous poems as ‘Island’:

I know The history of the island. The dimensions of the island. Waist, bust and hips. Seasonal dress. The singing of birds. The hidden spring. The flower’s fragrance.

As Yasuhiro Yotsumoto notes in the introduction to the volume, Rin Ishigaki spent all her working life as a bank clerk and as the main breadwinner for her extended family. With such an overwhelming responsibility, it is no wonder that in the superb ‘Motherland’ poetic free-dom is so celebrated. Rin Ishigaki employs the mountain ascent as a metaphor for the world of poetry, a world without prohibitions:

I was overjoyed by there being no notice On the trail I had just glanced back at It was a mountain trail where nothing like a notice should be. On the mountain top Where nothing like that should exist I yelled out without knowing why, If someone erects a notice here I’ll tear it out Unafraid I’ll tear it out regardless of the cost!

‘In Front of Me the Pot and Ricepot and Burning Flames’ is a poem of much formal care, beauty and resonance:

There have been for ages

Objects always placed

In front of us women,

A pot of sufficient size

To match our strength and

A ricepot designed especially for fat

Simmering shiny rice and

In front of the fire that we have inherited

from the beginning of history …

a resonance proclaiming a witty and gracious feminism:

In front of these beloved objects

Just like we cook meat and potatoes

With a deep love

Let us study politics and economics and literature.

Balance, humour and unwavering honesty distinguish her poetry. It is praised by the volume’s translator, Leith Morton, for ‘the simplicity and power of her diction. Rin Ishigaki’s words ring on the brain like the beat of a drum, sometimes the rhythm is gentle, almost comforting, but sometimes it breaks the silence like the cracking of a whip.’ If her style is rhythmic, one of her companions in this volume, Masayo Koike’s (b.1959) creates surfaces. Her words are alive on the page, with images deftly cut and folding into each other to create a vibrant surface formed of observation and perception.