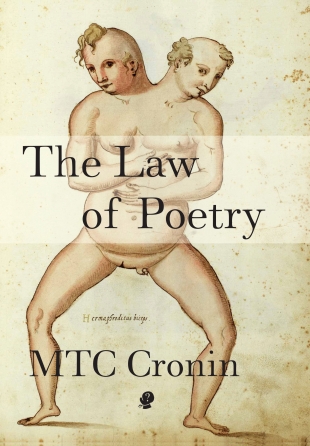

The Law of Poetry by MTC Cronin

Puncher & Wattmann, 2015

MTC Cronin’s ‘The Flower, the Thing’ is a favourite poem; one to which I often return. What strikes me immediately – and what stays with me – is its first word: ‘urgently’. That word sucks its reader in; it says that what comes after is ‘urgent’, is going to pull at you. It says, read on. The poem doesn’t disappoint:

Urgently, now, before us, the flower, the thing, entered before any window would allow it, always living, always posthumous, breached by the world and the unabstracted ...

And at its close:

... The flower says I have believed enormously, have you? And so, the vulture, the hat, the hand, the cobra, the dog, the sand, the arm, the trail, the reed, the two reeds, the foot, the bone, the leaving, the basket, the back, the folded cloth, the jar, the stand, the gold, the rope, the tether, the sound, the viper with horns and the sound of these like pins in the throat which are eased by water ... and always now, before us, the thing ...

This poem seems to gesture at something key to Cronin’s poetic. What is the urgency? What are we, as readers, to make of this insistence on the ‘thing’, and how do the ‘things’ Cronin raise in the poem help to resolve that question? They’re certainly not the articulation of the ‘no ideas but in things’ of William Carlos Williams, for example; that ‘urgency’ had far more to do with things as quotidian, more invested in the immediacy of sensory experience. Cronin’s naming of things seems more arbitrary – invested in language itself, the word (and world) as sign.

Of note is that ‘The Flower, the Thing’ is the final (and title) poem in Cronin’s The Flower, the Thing: A Book of Flowers and Dedications (UQP, 2006), a book that by its very name suggests ‘project’ over ‘process’. So too does The Law of Poetry imply a generative central purpose behind the work. Written over two decades, the collection catalogues ‘things’ physical and abstract, everyday and unexpected. Each poem is titled (or subtitled) ‘The law of —’ (with occasional variants), and the poems appear alphabetically according to subject, an arrangement that suggests, as per the naming of ‘things’ noted above, arbitrariness of ‘thing’ – and, indeed, of law: a system of rules which, in this case, might apply (or decidedly not apply) to subjects ranging from ants to babies to bones to broccoli to concrete to desire to ducks to eggs to facts to jungle … and so on. Indeed, while The Law of Poetry might seem lengthy at 261 pages, this feels only fitting given its compendium-like structure and scope.

Individual poems and the collection as a whole trace patterns and connections within language, evoking the idiomatic and axiomatic, and reminding us of the ways in which the figurative permeates much of our everyday speech. ‘The Law Of Catching The Worm’, for example, opens: ‘This law’s got you by the bright and earlys’, and puns ‘the prize is never one’, while ‘The Law Of The Rubber Glove’ reads in its entirety: ‘There is something rude about a rubber glove. / But is it something you can put your finger on?’ The writing is also attuned to the ideologies and ‘givens’ embedded in language, and to the subversive potential of language to self-reflexively call attention to its own constructions or fabrications. If language ‘rules’ us (or ‘speaks us’), The Law of Poetry reminds us that it is also a space of possibility and potentiality. What these poems reveal is the pleasure of idiosyncrasy, of language, of reimagining the ‘things’ that make up our world and the sense of agency poetry and its interventions can offer.

The collection frequently draws attention to supposedly small subjects: ‘a wild strawberry // Uneasily red and fading / to the pink smell of captured fruit // Trying to be less red / than the imaginary heart’ (‘The Law of Concrete’). Binaries, dualities and the symbiotic are also evoked and disturbed often, as in ‘The Law of Balance (or “The Imbalance”)’, which opens:

In poetry, evening and twilight balance perfectly. Mystery balances with any word you choose to weigh it against. Poetry, however, puts the whole world out of whack. When you read it you drift up or down while everything else goes in the opposite direction.

The poem emphasises the suggestive potential of words, with lines such as: ‘When you read “womanliness”, your hands, / which had been empty, are suddenly full of breasts’. Ultimately, it calls for ‘a poet who can take / the poetic punishment out of evening and twilight.’ It reads:

Such a person will have no regard for beauty and a thoroughgoing disregard for how things might be put. Such a poet knows that there are no strange ways to say ‘I love you’ and that the orange-purple-red glow that accompanies the particular time under discussion violates more, much more, than a sense of the well-ordered.

‘The Law of Reality’, too, conjures familiar themes and icons – stars, love, presence and absence, sand and snow – and strips them of any kind of dubious sincerity. Instead, the imagery takes on an oneiric quality; ‘concrete and trees / continually swap positions’, and the poem ends:

This has nothing to do with reality where the star breathing sounds like sand melting into snow.

‘Chance’s Permissive Laws’ similarly pairs the immediate and intimate with the infinite and ineffable. The poem comprises a startling list of negations, among them: ‘Not that the meteor is beauty too close’; ‘Not that memory is like elastic stretching back to hurtle you’; ‘Not that all steps are towards death’, to conclude:

But that you allow all these things. That you give them a chance to destroy you. That you afford them the chance to let you live.

These are just some of the tones and preoccupations of this collection, which ranges in vein from the unsettling to the comic – sometimes in the space of a few lines. This poetry is every bit as urgent in mood and momentum as it is keenly felt.