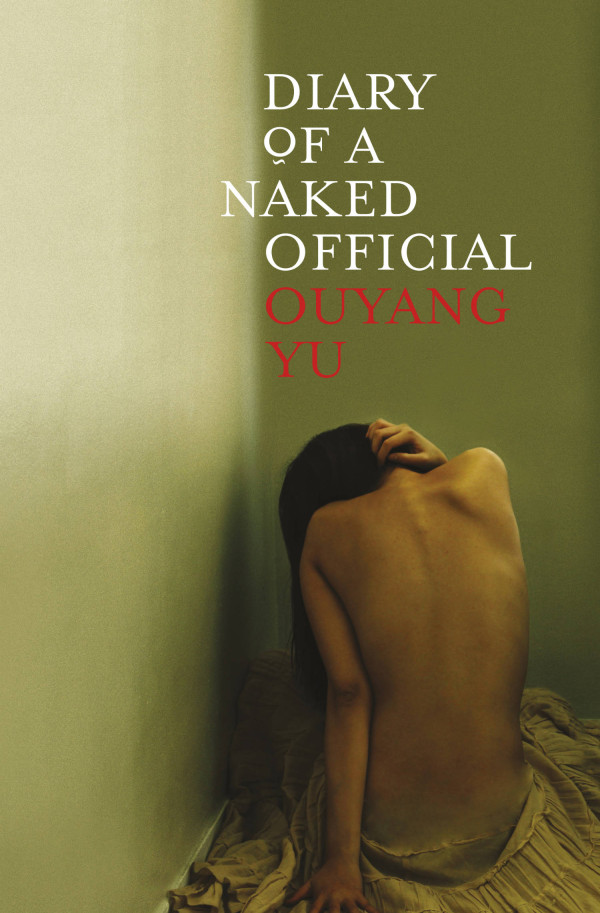

Diary of a Naked Official by Ouyang Yu

Transit Lounge Publishing, 2015

Well known as a poet, translator and literary critic, Diary of a Naked Official marks Ouyang Yu’s second foray into the novel form. His first, Loose: A Wild History (Wakefield Press, 2007), mixes fiction and non-fiction, poetry, literary criticism and diaristic writing. His second novel is more circumscribed, but still abundantly displays Yu’s interest in metafiction and ficto-criticism, as well as an extensive, playful way with literary allusion.

The ludic play begins with the information that the book we read allegedly has been discovered on a USB dropped on a Melbourne tram (8). The text thereby uncovered is ‘Diary of a Naked Official, written in English in its entirety’ and signed ‘Shi Ma,’ a name unknown to our literary intermediary and a name that Google cannot make any less mysterious. Although the text ‘reads like a mere diary but in certain places it sounds like a novel,’ our literary mediator settles on the status of ‘diary’ (9).

This trope of the adventitiously encountered, mediated text recalls the origin of the novel as a genre when fiction was offered up disguised as archival material, translation, autobiography, as with Don Quixote and Robinson Crusoe. In this case our nameless narrator is a mid-40s deputy-director of a publishing company located in an unnamed city in mainland China. He has contrived successfully to buy permanent resident status for his wife and child in Sydney, Australia, and the money he has embezzled from his publishing firm is also safely overseas with the relocated family. This allows for one of the meanings contained in the book’s title: in contemporary Chinese terminology a ‘naked official’ is ‘one who has nothing to fear when exposed because his family is safely installed overseas with his money’, which means that should the Chinese state denounce him, he can take the fall safe in the knowledge that his family is well provided for outside China. Near the book’s end we learn that although our confessor has to clear his name ‘by telling the whole story about my corruption’, he is comforted by the fact that his ‘wife and daughter are now safely accommodated in Australia beyond the reach of Chinese laws’.

Another meaning refers to ‘luoili’, a form of ‘naked divorce’ in which a woman is so determined to leave a marriage that she departs without making any claim on children, property or other wealth (61). A third meaning is revealed near the book’s end when our diarist decides to destroy all photographic images and computer files accrued over his years of brothel creeping:

I did not want any of those to fire up anyone else’s fantasy … Least of all did I want them to be released online and used against me. One needs to live naked offline and be virtually anonymous online, the Internet being a hell of knowledge, as destructive as constructive, like a river into which people chuck all rubbish, garbage and excrement … (186-187)

The metafictional elements in Yu’s book are rationalised by having the narrator work in a publishing house, with daily concerns about what manuscripts to publish, what books to buy for translation into Chinese. Such a person is likely to read books in his spare time, and so we find references to contemporary risqué writing involving sexually-driven male narrators, Michel Houellebecq’s Whatever, Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, alongside references to de Sade and Nabokov. In the case of Nabokov we might expect the allusion to be to Lolita, another mediated text initially published by Olympia Press in Paris, and the subject of censorship trials à la Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover. But the reference is rather to Pale Fire: ‘Done a few books, including Pale Fire by Nabokov. The poem is okay but too designed. In fact that’s what the whole book is. Can’t finish the rest of the notes and stuff. Too pretentious for my liking’ (22). Elsewhere he tells us he only made it 80 pages into this ‘real boring book’ (38), which suggests he might be as unreliable a narrator as Nabokov’s. The ‘okay poem,’ as I recall has wonderful couplets like, ‘I was the shadow of the waxwing slain / By the false azure of the window pane’. When Nabokov’s narrator attends a university gathering at a colleague’s house, he walks into a room of people mostly unknown to him, and assures us, ‘I soon put everyone at their ease,’ by which point we are aware that our narrator is bonkers. This is only a small section in Yu’s novel but it displays an adroit way with literary allusion.

Our diarist fits Foucault’s description (in The History of Sexuality) of man ‘as a confessing animal’, at one point saying, ‘the diary is the only confessional, in which the man listens to himself, his other self or selves, or reads it or them, the way Cioran succinctly puts it, ‘All men are fragments of himself” (90). He doesn’t know why he wants sex, ‘I just want it out, for some reason’ (46). ‘It’ is described several times, by its possessor and its many receivers, and our naked official seems quite happy with his ‘big instrument … my non-Party member, erect and dark red’ (192). If one were seeking a local literary context in which to place Yu’s book it might be the period from the mid-1990s, which saw Justine Ettler’s first novel, The River Ophelia (Picador, 1995), advertised in an indie rock band way with posters on telegraph poles all over Potts Point and Darlinghurst, go on to sell 30 thousand copies. Linda Jaivin’s Eat Me (Vintage, 1997), her contribution to an explicitly sexualised literary fiction from Australian women writers, was an international bestseller. Nikki Gemmell’s The Bride Stripped Bare (London: The Fourth Estate, 2003) initially appeared as authored by ‘Anonymous’, and is now badged as a ‘Modern Australian Classic’, and Leigh Redhead and others would arrive on the scene later.

Brian Castro’s Shanghai Dancing (Kaya Books, 2009) early on announces, ‘My first words came out fully formed. I called for whores’, and another novel from Transit Lounge, Patrick Holland’s The Darkest Little Room (2012) is a further, excellent entrant into this field of literary sexual fiction, as are two compelling books from English writers, Stephen Leather’s Private Dancer (Monsoon Books, 2005) and Lawrence Osborne’s novella, The Ballad of a Small Player (Vintage, 2015). If in terms of a relatively immediate Australian and south-east Asian literary context, Yu’s book can be absorbed into this emerging sub-genre – and admired as a very engaging contribution, as a diaristic work – we can also link Yu’s book back to the seventeenth century with Samuel Pepys’s Diary. Pepys tells us that although he was reading ‘a mighty lewd book’, it was ‘yet not amiss for a sober man once to read over to inform himself in the villainy of the world’.